AWG0000.05.01

Medieval (1493)

Material: Ink printed on paper, with handpainted illustrations

Dimensions: 49cm tall, 32cm wide

Condition: Good with paint well preserved. There are some aging spots. Rectangular marks at the top of the verso side appear to have been left by tape one used to secure the page

Provenance: Unknown

Date of acquisition: Unknown

Research by: Julia Berutti, ’23

Detailed description of form/shape:

Pages 135r (recto) and 135v (verso) of the Nuremberg Chronicle. Large, handmade paper with letterpress text and handpainted woodcut illustrations. Latin text.

Detailed description of decoration:

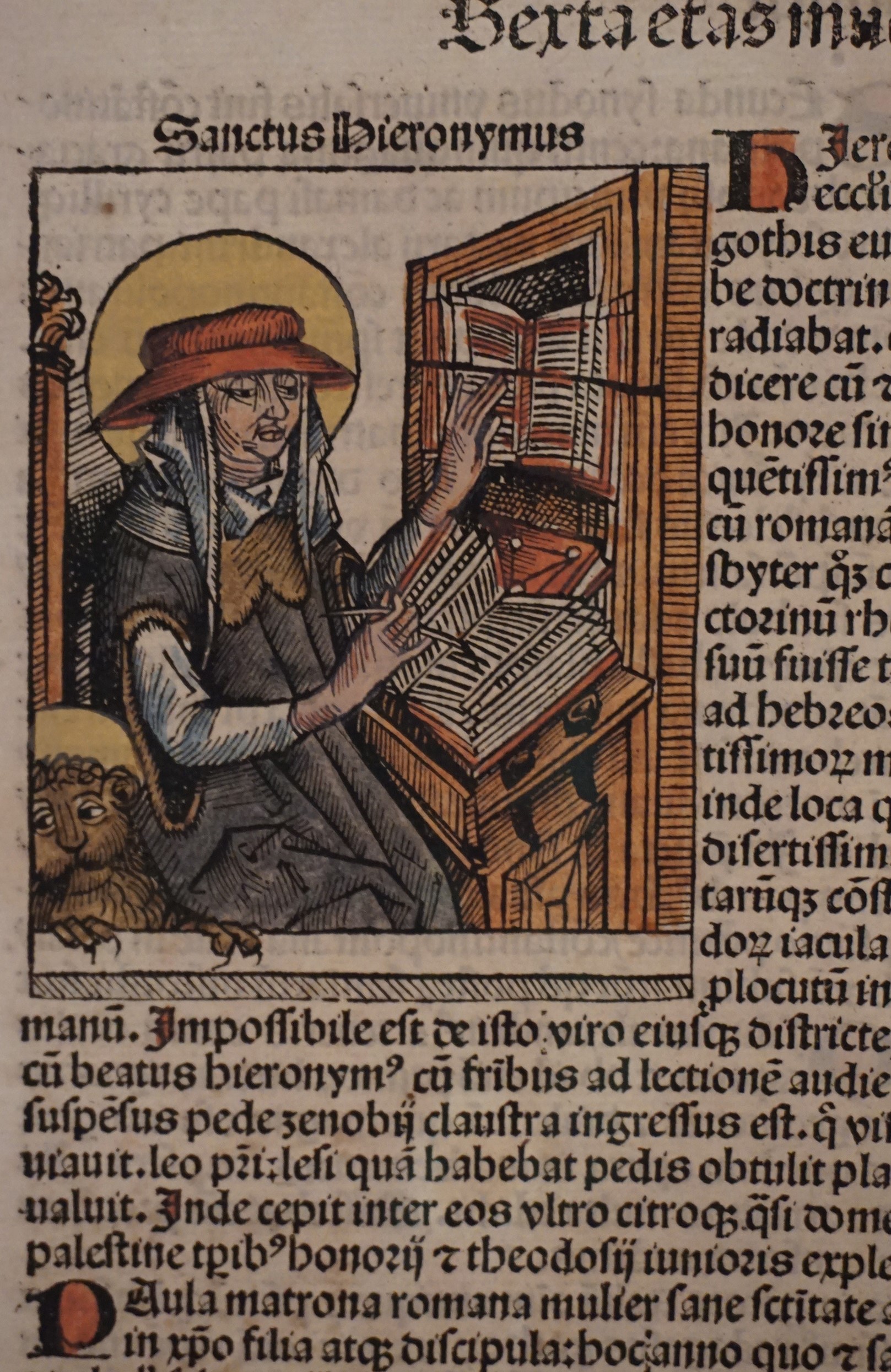

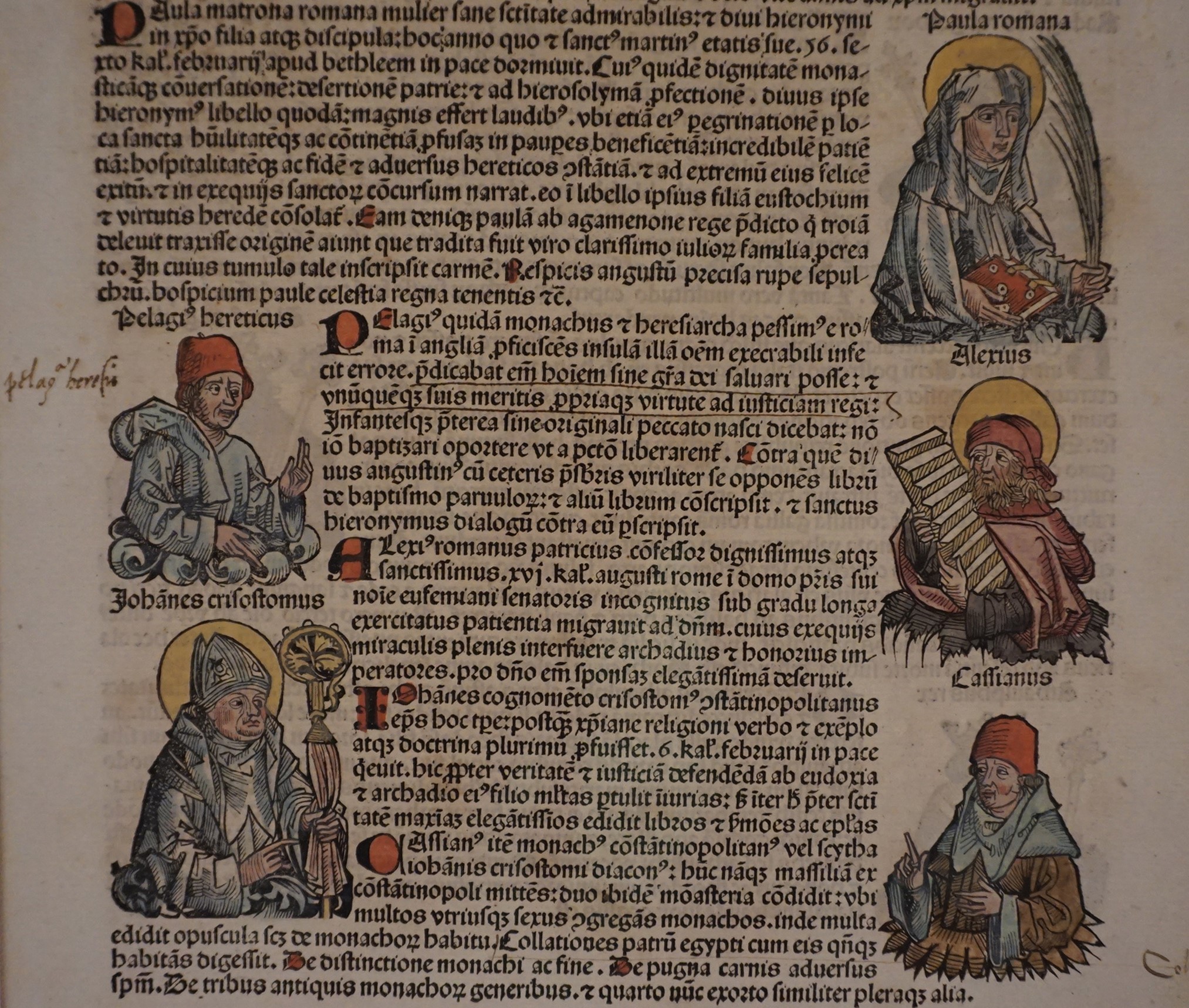

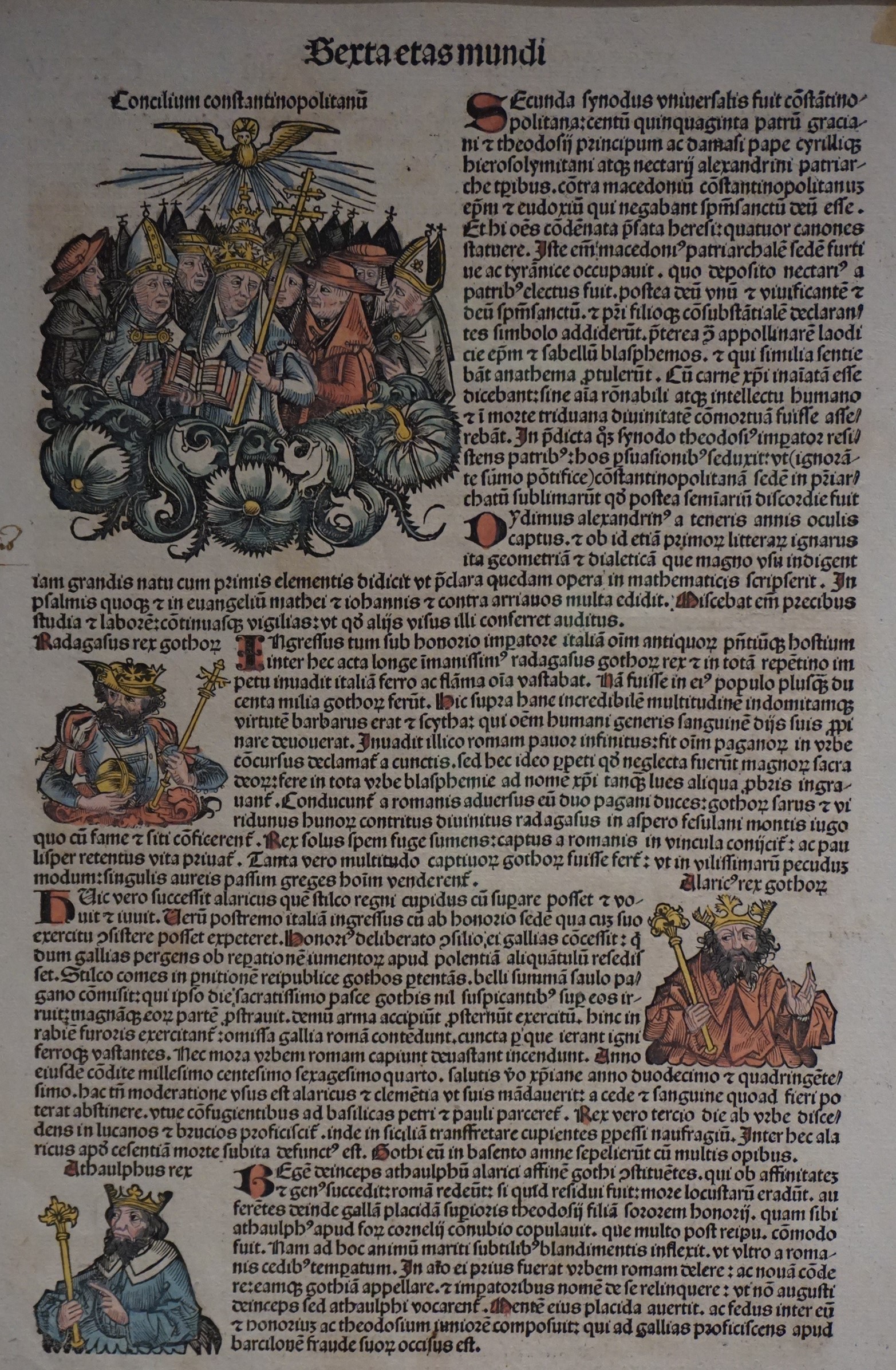

On page 135v, the topline reads “Sexta aetas mundi” (“Sixth Age of the World”). 19 letters beginning sentences are highlighted in red ink, and the same red appears in three of the four colored images throughout the page. The largest image in the top left corner of the page depicts multiple figures, many dressed in biblical and regal garb. The caption helps to identify the scene as the Second Ecumenical Council, held in 381 CE at Constantinople. Three other images depict other rulers of the time, including Radagasus and Alaric, kings of the Goths. The other side, page 135r, features six images of figures. The largest in the top left corner depicts Saint Jerome (Hieronymus) writing in a book, with the lion he had healed and adopted as a pet peeking out of the lower left hand corner. The other five figures, towards the bottom of the page, wear varying kinds of clothing and each holding different objects. There are some handwritten marginal comments on each side.

Comparanda:

For a general page, see St. Louis Art Museum 86:2012. For a large picture, see British Museum 1870,1008.1938.1-136. For a detailed description of this page in particular, see Beloit College Nuremberg Chronicle. The entire text is also available in the public domain.

Discussion:

Also referred to by its Latin title, Liber Chronicarum, the Nuremberg Chronicle is a 1493 text written by Hartmann Schedel and printed by Anton Koberger. The full text is an encyclopedic illustrated summary of the geography and history of the world. Schedel, an avid supporter of empires as institutions, praised the emperor of the time, Frederick III, and told the history of empires, beginning with Julius Caesar. Schedel’s personality reads through some of the other parts of the work, too, as much of the geographical descriptions of cities were based off of Schedel’s own travel experience (Duniway 1941, 25). Anton Koberger, the printer, ran the largest printing and publishing company in Germany at the time, owning twenty-four presses. In the time prior to printing the Nuremberg Chronicle, Koberger’s work was mostly made up of scholarly works, as the church made it illegal to print the Bible in any language other than Latin. Because this work told biblical stories through images as well as the text, it became somewhat foundational for the Protestant Reformation in 1517 (Duniway 1941, 32).

The editions of the book were very large, each consisting of 326 pages, with 1809 illustrations made by 645 unique woodcuts (“The Nuremberg Chronicle”). The text and images depict the Seven Ages of the World, along with twenty-six cityscapes and numerous historical figures (“The Nuremberg Chronicle | Duke”). Due to the success of the original 1493 printing, other printers began selling their own editions through the end of the 15th and early 16th centuries (“The Other Nuremberg Chronicle”).

The books were sold both bound and unbound, and the original binding was usually made of wooden board covered in pigskin or dark leather, decorated by stamps (“The Nuremberg Chronicle Selections from the Rare Book Room”). This page of the Chronicle features 10 of the famous images, as well as great examples of the gothic font used throughout the text. While the quality of the illustrations is high, in full color. Though the color is more faded than other copies today, it suggests that the original owner was rather wealthy.

Bibliography:

Cambridge Digital Library. “Treasures of the Library: Nuremberg Chronicle.” Accessed October 4, 2021. https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/PR-INC-00000-A-00007-00002-00888/316.

Duniway, David Cushing. “A Study of the Nuremberg Chronicle.” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 35, no. 1 (1941): 17–34.

Saint Louis Art Museum. “Nuremberg Chronicle.” Accessed October 4, 2021. https://www.slam.org/collection/objects/56323/.

Schedel, Hartmann, Wilhelm Pleydenwurff, and Michael Wolgemut. The Nuremberg Chronicle (Liber Chronicarum). Anton Koberger for Sebald Schreyer and Sebastian Kammermeister, 1493. https://www.wdl.org/en/item/4108/.

The British Museum. “Print; Book | British Museum.” Accessed October 4, 2021. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1870-1008-1938-1-136.

“The Nuremberg Chronicle | Duke.” Accessed October 4, 2021. https://alumni.duke.edu/magazine/articles/nuremberg-chronicle

“The Other Nuremberg Chronicle | THE GARGOYLE BULLETIN.” Accessed October 4, 2021. https://pages.vassar.edu/library/2014/09/nuremberg-chronicle/.