AWG0000.02.01

Byzantine, Late Roman to Byzantine period (4th-14th century CE)

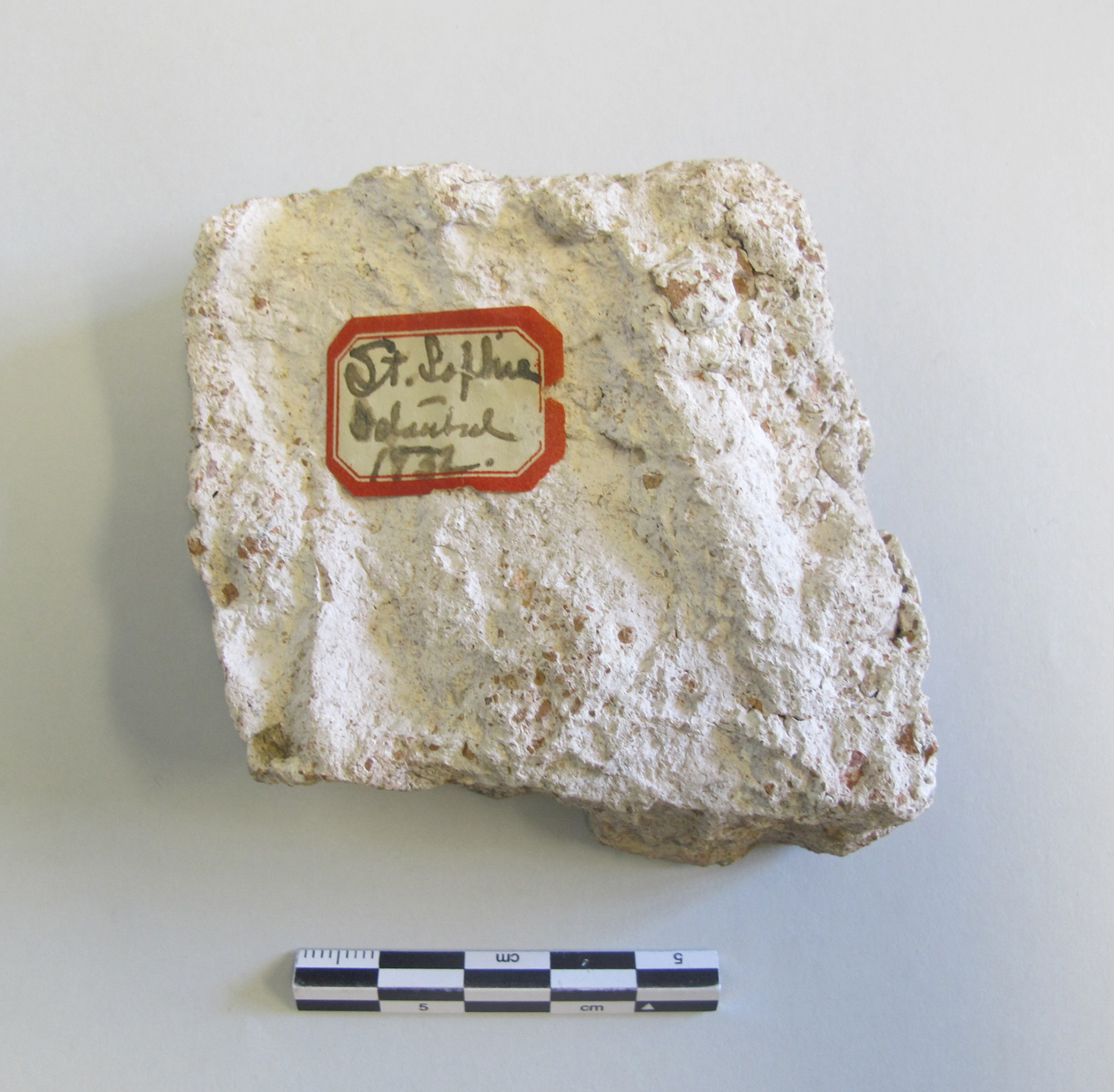

Material: Stone embedded in mortar

Technique: Opus sectile

Weight: 157g

Dimensions: Max. width 5.58cm, max. height 10.4cm, thickness varies from 5.58 to 4.2cm

Condition: The fragment is broken and irregular on all sides but the inlaid surface or face. A small paper label with a red border attached to the back says, in cursive ink, “St. Sofia, Istanbul, 1932”

Provenance: Istanbul, said to be from Hagia Sophia

Source/donor: Unknown

Date of acquisition: Unknown (probably prior to 1932)

Other notes: The red-bordered label matches the style of labels on items in the Lora Robins Gallery that were once in the Biology Museum in Maryland Hall. Because that museum opened in 1932 and many of the items in the Lora Robins Gallery still have labels from that collection that are also dated to 1932, it is probable that this date reflects not the date of the piece’s original arrival to the university but rather the date of its labeling for the Biology Museum.

Research by: William Hunt, ’23

Detailed description:

Four different types of cut stone are embedded in the mortar: white marble or limestone, a dark grey stone, an emerald green stone (serpentine), and a dark purple/maroon stone with small white flecks (porphyry). There are approximately eleven whole pieces of the white stone, five whole pieces of the dark grey stone, one whole piece of the green stone, and two whole pieces of the dark amethyst stone. The shapes range from parallelograms, to squares, to hexagon, while the geometric design includes a singular dark grey square surrounded by four white hexagons in a sort of rosette motif. There are also green hexagons and dark purple hexagons in a seemingly irregular pattern mixed throughout the design. Most of the dark grey squares are split in half.

Comparanda:

Similar rosette-like opus sectile patterns are found in the katholikon of the Iveron monastery in Athos, constructed in the 11th century (Liakos 2008, fig. 4). The floor of the nave is particularly comparable, with dark square-shaped cut pieces of stone surrounded by lighter colored triangular cut stone pieces in a rosette formation.

Discussion:

Opus sectile is the name for a method of decorating pavements or walls with colorful stones cut into geometric shapes and laid in geometric patterns. It began in the Roman period and was especially popular in Late Roman and Byzantine churches and palaces, with a notable revival in Italy in the 12th- to 13th-century ‘Cosmati’ style. The stones used in this opus sectile fragment are remarkable for their rarity and value. Green serpentine and purple porphyry are among the most valued materials used for opus sectile when available (Fant 2012). Opus sectile was commonly paired with mosaic and is typically found in early Christian churches such as the 6th-century basilica at Mahatt el Urdi in Palestine, where opus sectile was used for the nave and mosaic for the aisles (Britt 2019).

The main question surrounding this piece is whether or not it came from the famous church of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, as the handwritten label on the back suggests. The pattern is not similar to known opus sectile designs in Hagia Sophia. Most of the church was originally paved with large marble slabs, not opus sectile designs (Swift 1940, 71). One section of the nave, known as the ‘Omphalion’ (“navel of the Earth”), is paved with opus sectile and does include some stones of similar colors (white, purple, and green), but their shapes and the patterns they form are larger and more circular and rounded than on our piece, and that pavement is later than the original building, probably dating to the late 14th-century renovation (Swift 1940, 72; Mathews 1976, fig. 31-63). Opus sectile designs inlaid in some parts of the walls (Kähler and Mango 1967, figs. 63-64; Mathews 1976, figs. 31-59, 31-62, and 31-71) are also very different, with figural, architectural, or vegetal motifs rather than the abstract patterns on the piece in this collection. Therefore, this fragment likely came from another building in Istanbul or nearby and was sold as tourist souvenir with a false attribution to Hagia Sophia.

Bibliography:

Britt, Karen C. “Early Christian Mosaics in Context.” In The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Archaeology, edited by D.K. Pettegrew, W.R. Caraher, and T.W. Davis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019. https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199369041.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199369041-e-16?rskey=gpzvbo&result=2

Fant, J. Clayton. Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World. Oxford Handbooks Online. 2012 https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199734856.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199734856-e-6?rskey=gpzvbo&result=5

Hagia Sophia Research Team. 2017. “Omphalion” Hagia Sophia. https://hagiasophiaturkey.com/omphalion

Kähler, Heinz., and Cyril A. Mango. Hagia Sophia. With a Chapter on the Mosaics, translated by Ellyn Childs. New York: Praeger, 1967.

Liakos, Alex. “The Byzantine opus sectile floor in the katholikon of Iveron monastery on Mount Athos.” Zograf 2008: 37-44. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Byzantine-opus-sectile-floor-in-the-katholikon-Liakos/82409f2653385b8076b751b88301508ef0bf8a49

Mathews, Thomas F. The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul. A Photographic Survey. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1976.

"Opus sectile". Encyclopedia Britannica, 5 Feb. 2008, https://www.britannica.com/art/opus-sectile.

Swift, Emerson Howland. Hagia Sophia. New York: Columbia University Press.