As our students and faculty are busy completing and grading final assignments, respectively, I have been reflecting on the semester. This spring, I taught the cross-listed leadership studies/economics class Competition, Cooperation, and Choice. The course covers ground from Bernard Mandeville’s early 18th century writings to 21st century experimental economics, with plenty of game theory in between. It was a joy and a challenge to return to the classroom after a five-year hiatus. I learned a great deal from our students, as they forced me to read and re-read the texts and answer new questions.

As our students and faculty are busy completing and grading final assignments, respectively, I have been reflecting on the semester. This spring, I taught the cross-listed leadership studies/economics class Competition, Cooperation, and Choice. The course covers ground from Bernard Mandeville’s early 18th century writings to 21st century experimental economics, with plenty of game theory in between. It was a joy and a challenge to return to the classroom after a five-year hiatus. I learned a great deal from our students, as they forced me to read and re-read the texts and answer new questions.

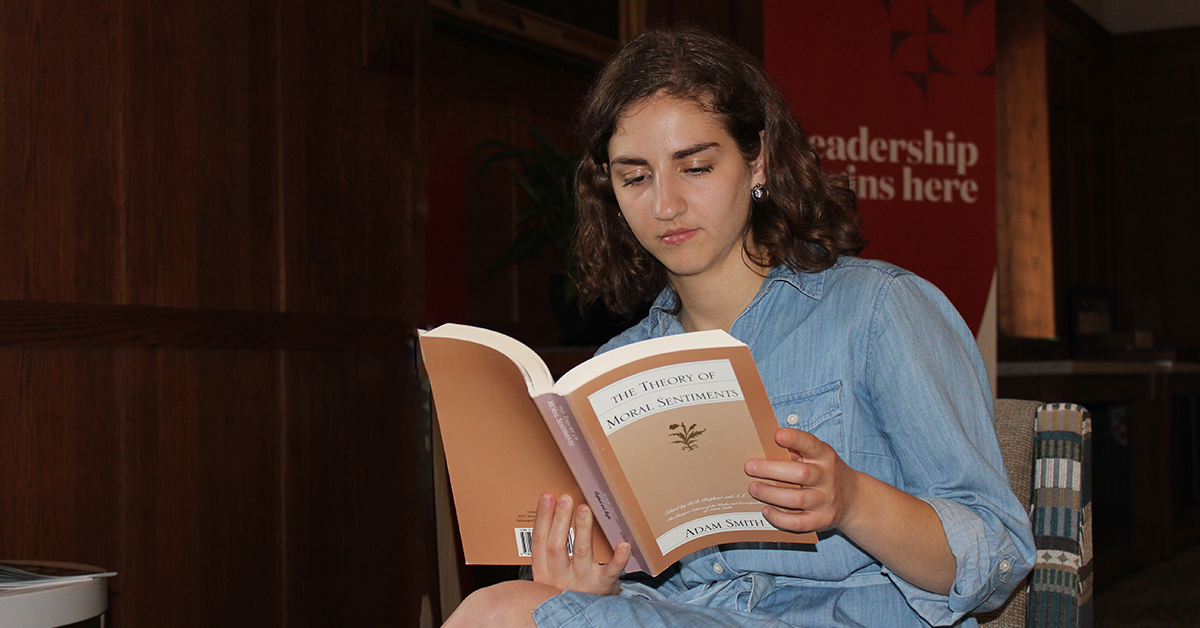

First, I was pleasantly surprised by my students’ willingness to read old books! In addition to Mandeville, we read most of Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments, a good portion of his The Wealth of Nations, John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty, W. S. Jevons’ “Married Women in Factories,” F. A. Hayek’s “Use of Knowledge in Society,” portions of Thomas Schelling’s The Strategy of Conflict, and Vernon Smith’s “Two Faces of Adam Smith.” None of those is easy reading, and some are quite difficult.

I was not surprised by their enthusiastic participation in classroom experiments. In dictator, ultimatum, prisoner’s dilemmas, and public goods experiments, they displayed a willingness to think through and discuss possible outcomes and tie their behavior to the readings. In the course of a game of trade, I learned two surprising facts: orange-flavored Gatorade is not a highly prized good, while small bottles of shampoo and hand lotion are. Who knew?

My students were analytically sophisticated. They absorbed and appreciated the technical details of economics, including how Smith (and others) differ from much 20th century economic analysis and how experimental economics represented a return to a different sort of economics, one that investigated the role of language and learning rather than positing formal, constrained optimization problems.

They were also constantly on the lookout to connect our economic analysis to questions about leadership. We talked about self-governance and policy as it relates to governing the self and the commons. We examined socially optimal outcomes in experimental and game theoretical contexts. We had lively debates about immigration, international trade, drug prohibitions, and access to high-quality education. We spent much time discussing the role of leaders and effective leadership in these settings.

This evening, we will gather one more time for dinner at a nearby restaurant. Beyond debriefing about the class—I am certain there are ways I can improve it!—I have told the students I hope to learn from them. I have challenged them to think about what they might change at the University of Richmond (and the Jepson School of Leadership Studies) and what they hope will remain unchanged. I look forward to learning from them in the course of our discussion!