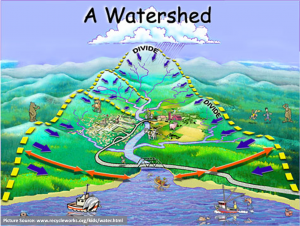

“Any area of land from which water and materials drain to a common point, such as a stream, river, pond, lake or ocean.”

~Definition of a watershed, first day of class

We came in, we sat down, and we listened. That is how the first couple weeks of Geojames went. Personally, I had never taken an environmental class and the last geography course I took in middle school consisted of memorizing states and capitals and writing them on a map. Therefore, I was essentially coming into this SSIR with a clean slate.

To be honest, in the beginning, I was not exactly clear on what the ultimate takeaway from this class would be. We learned a lot, but none of it seemed to connect. Similar to my middle school experience with maps, we learned about watersheds, each marked with boundaries, as though each one thrived completely independent of another. What was the point? However, as we dove deeper into the semester, the lines bounding each of those states in the middle school map seemed to fade away—the lines bounding each watershed with a different 8 digit hydrologic unit code seemed to dissolve—and everything suddenly linked. Because I realized, the environmental impacts of our actions do not stop at these imaginary boundaries that exist only on maps; these places and regions are all connected, and our daily actions have ripple effects on all of these places that could last thousands of years into the future.

I began to form my own definition of a watershed.

“An area of land within which all living things, and essentially, the community, is linked by, dependent on, and driven by, a common water course that serves as the focal point.”

~Definition of a watershed according to Sanitra, November 26, 2016

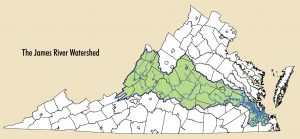

Yes, within our watershed—whether it is the University within Little Westham Creek Watershed or the city of Richmond within the James River Watershed—we are a community. However, as stated earlier, the lines are blurred. It is not just our small little place we call home that I need to pay attention to, or in which I can instigate change; I need to look at the big picture.

In John Lehrer’s “Urban Myths” he focuses on the idea that larger cities have faster “metabolisms” than smaller cities. If one translates this notion to rivers, the James has one of the fastest metabolisms in the state! However, most efforts to improve and protect it are concentrated solely within the city of Richmond, a city that makes up a small part of the full River. While Richmond—with its rich history of its connection to the River mentioned in In River Time and its most recent efforts to clean up the polluted waters through the Clean Water Act and through efforts of RVAH2O —may be somewhat aware of the role of the River due to the city’s overwhelming pride in it, the rest of the region seems to lack this focus, dedication, and overall awareness. According to the State of the James report, with a grade of a B-, “the river’s overall health has improved, but there is still much work to be done.” With terrible grades on nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment reductions, I for one, am concerned. As Jack states when describing the importance of group mentality in accomplishment of a common goal, “without a collective, distinct and conscious passion for the James, there is no hope for its future. Positive change is dependent upon shared culture.” From the start of the river in the Appalachian Mountains, through the confluence of the Cowpasture and Jackson rivers, all the way down to Hampton Roads and the southern portion of the Chesapeake Bay, there needs to be a shared importance and value for the river for there to be a willingness to save it.

The significance of this idea of a common culture really shined through on our Reedy Creek visit. As mentioned in my earlier post, I was very impressed with how aware the residents surrounding the creek were of the government’s plans for restoration and how, by displaying the black and white signs in their front yards, they were passively protesting the proposed project as one. Michael states that, in order for their efforts to not go in vain, residents have to “exercise their most fundamental right by electing to office leaders who share the best interest of the creek at heart.” This applies to the watershed as a whole as well. Similar to the government in Portland, which has implemented a green-friendly city bike system and public transportation bridge, there needs to be environmental leaders within the local and state government who display those required traits of passion, knowledge, and power and want to see a positive change in the James in the future.

On a much larger scale, the whole world, comprised of 71% water, is all one big watershed. Looking at problems from a small scale can be beneficial, as viewing the world through 6 digit hydrologic codes can help us see the impact our personal efforts are making on the environment around us. But the world is larger than that, and the impact we, as a collective international community, have on it is greater as well. As Parr mentions, “if we better understand this larger sense of community, then we can push more people to take action to protect watersheds all around the globe.”

According to my definition of a watershed, we, as the human race, are all connected by our common water course. Geojames, through the service trips, class outings, and community events, sharpened my awareness of this and of how much of an impact humanity has on nature, locally and globally. The Earth is in trouble; its population is increasing drastically, but the amount of sustainable resources it possesses is limited. Although I alone cannot make a momentous impact, educating and encouraging others could. Informing people about their surrounding environment and getting them excited about the place they live—their home—can make them want to make a long-lasting difference. Ultimately, that, in fact, is they key to a sustainable future; creating a group of people with a will to work towards one.