Black Girlhood, Interrupted – Chapter 7

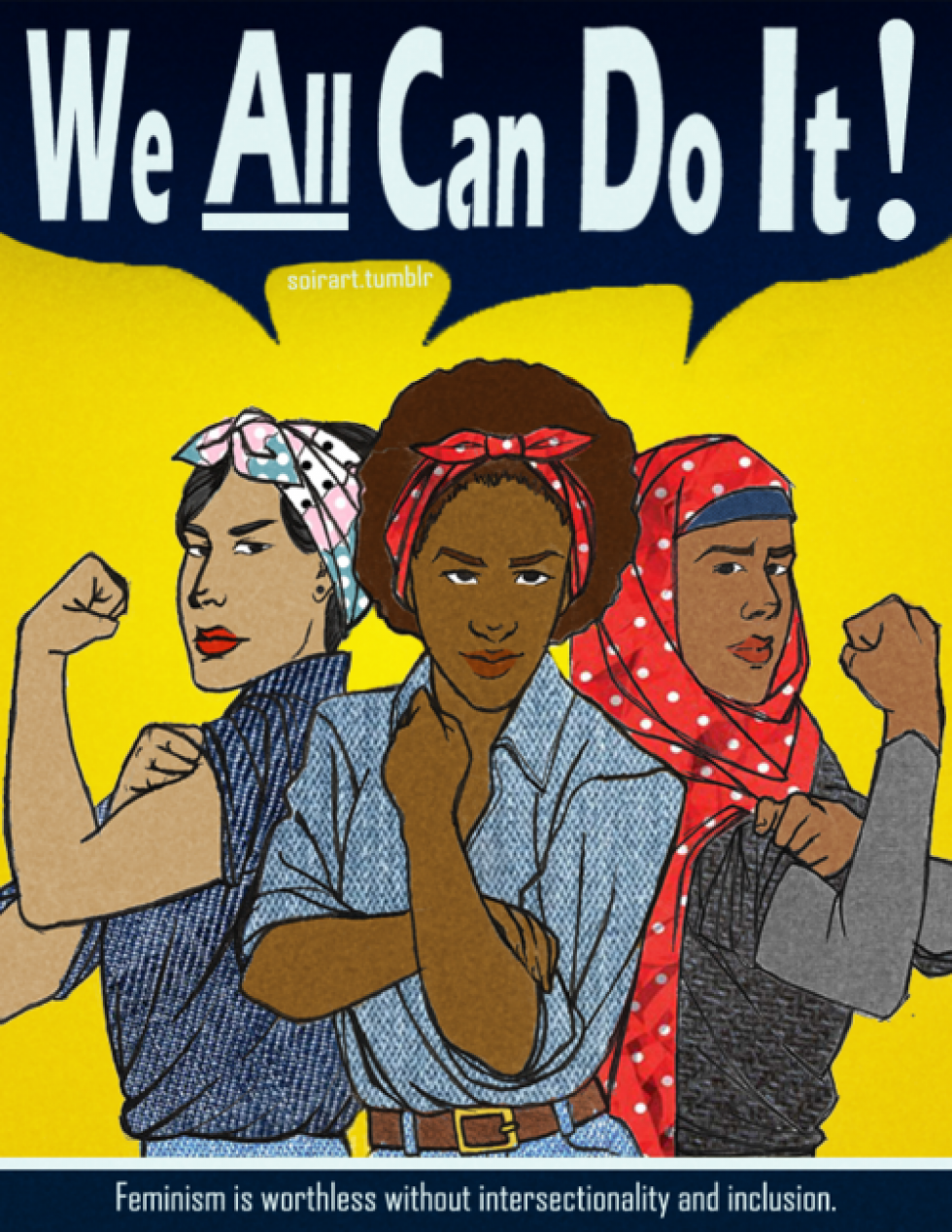

In this chapter, Cottom shares her experiences of being a young black girl. She shares how society perceives Black young girls and women. From a young age, Cottom realized that it was not easy to read about girls, let alone about Black girlhood. As she was going through school, she read mostly about heroic man, or fictional characters, rather than about girls and their experiences. It was not until college that Cottom had the chance to read about black girlhood and the life of black women. While reading about Black girlhood, she realized that the easiest way to locate a girl in a story about a woman is connecting her to sexual trauma. Black girls and women’s stories oftentimes contained experiences about sexual assault which is tied into what Black womanhood is. Growing up Cottom learned the power dynamic between sexual assault predators and sexual assault survivors/victim work in the black community and in society as a whole. After experiencing misogynistic comments and having two defining incidents with her cousin and dad, she realized that Black girls can never be truly seen as victims of sexual predators. Men and women excuse violence against black women and girls. If a man, or society, perceives a black girl as “ready” for what a man wants from a girl, then by just existing she has consented to his treatment and she will never be the victim. This notion of a black girl or woman being “ready” is highly problematic, especially since researchers have proven that black girls are perceived as more adultlike than their white peers. Adults perceive black girls to be more knowledgeable about sex, they perpetuate this idea that a black child is responsible for the desires that adults project onto her. If black girls are never perceived as a child, they will not receive the protection of childhood. This system of neglect and abuse is mostly ignored in social and education policy. This perception of being “grown” from a young age, exposes black girls and women to more incidents of sexual assaults without having the means to defend or protect themselves. Cottom shares how legally reporting sexual assault, abuse, or violence is a disadvantage for all women, but it is especially unfavorable for black women. Cases of rape, sexual assault, abuse, and violence are proven in court by “evidence-based” proof which means that one has to have physical evidence of a bruise or a wound. The tools used to capture these bruises are not built to find marks in dark women, this automatically puts black women in a position of disadvantage. The system fails black women by design.

Girl 6 – Chapter 8

In this chapter, Cottom writes about her thoughts on how she wants black women to have a full-time job as an opinion writer at a prestigious publishing company. She shares the barriers and difficulties black women would have to go through to make it in the industry. All throughout the chapter, she uses David Brooks, a prestigious journalist for the New York Times, to point out what is inherently wrong with the industry. Cottom explains how Brooks wrote an article on deli meats and used it as a metaphor to convey how the upper-middle-class Americans had left everyone else behind. She points out that even if this essay had no real substantial meaning or it failed, Mr. Brooks will be back to his job because that’s what he did, write for the New York Times. She wanted black women in the world to have the freedom to be banal as a matter of course for her job, wanted them to be well compensated, protected, and free to fail. She wanted Black women to talk about whatever they desired for a publication where whatever it said mattered, just like David Brooks did with the deli meat. She knows they are black women journalists that have columns in some magazines or newspapers, but writing is their 4th or 5th job. The industry has many flaws when accommodating black women in the industry. One of the flaws with getting a job in this industry is how writing is democratic. Writing well required costly and time-consuming resources that are mostly achieved by having a prestigious job. Another barrier is the required experience for these jobs. Most companies seek employees that have had previous internships in media. Most internships in media or unpaid, which puts in a huge disadvantage low income, first-gen college students, immigrants and children of immigrants, and black people. Statistically and systematically these demographics are unlikely to sustain an unpaid internship to gain experience. One way of overcoming these barriers can start from within the company. Prestige employees can start engaging more with talented black women to learn from them and see how they can add a different and valuable perspective to their company. As Cottom points out, even following more black women on Twitter matters. Twitter is easy, it cost nothing to gauge with someone who won’t move into your neighborhood or sit beside your desk. The world needs writers that provide different views of an unfair and unjust world, even if some people don’t like it, and black women can bring these different perspectives.

- In Chapter 7, Cottom shares different ways people treat young black girls more adult-like than their peers. Loretta Ross also talked about this during her discussion of Reproductive Justice. How does this treatment towards Balck girls affect their development and social interactions? What types of disadvantages or barriers do these girls face?

- This article from Georgetown Law goes more in-depth about this situation in America. If you would like to read more on this topic I highly recommend it. https://www.law.georgetown.edu/poverty-inequality-center/wp-content/uploads/sites/14/2017/08/girlhood-interrupted.pdf

- How is the argument “black men are too oppressed to oppress” in Chapter 7 problematic? How did this argument help notorious men like R Kelly, Myke Tysons, and Charlamagne the god, be defended by many in the black community?

- In Chapter 8, Cottom shares some examples of articles that she would write if she were free of judgment and repercussions, what audience did these articles target? Why do you think Black women haven’t gotten the opportunity to earn a living wage off writing articles for prestigious publishing companies like the New York Times?

The trope or stereotype that black girls are sexually promiscuous and need less protection and nurturing than white girls is incredibly dangerous because as Cottom shares in the chapter, “Black Girlhood, Interrupted”, these harmful falsities make black girls more susceptible to sexual trauma. Assuming that women are “ready” and “hos” is problematic generally, but specifically applying it to black underage girls is incredibly disturbing. As Cottom notes, there have been rumors about R. Kelly since the 90s. However, it is vital to point out that he was not arrested until after the MeToo movement, led by white women. This chapter points out how Black women have been taken advantage of by not only white men and women, but also Black men. A recent example of this is Tory Lanez shooting Megan Thee Stallion, and the resulting skepticism and judgement of Megan Thee Stallion despite being the victim in the situation. Here is her Op-Ed in the New York Times, I highly suggest! : https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/13/opinion/megan-thee-stallion-black-women.html . Cottom says that “black men are too oppressed to oppress”, meaning that they face enough oppression due to mass incarceration and the harmful effects of the prison industrial complex, so it is not possible for them to oppress others, especially black women. However, this concept is harmful, as it is the same concept that allowed R. Kelly to continue to abuse young black women and girls for years without reprecussions. Cottom references her cousin calling Desiree Washington, the eighteen year old who was raped by Mike Tyson, a hoe. By blaming the victim and trying to make up excuses for the situation, the truth of these tragedies are effectively called into question and delegitimizes the black female voice.

In response to your second question, the argument “black men are too oppressed to oppress” creates an environment void of accountability. While it is true that black men face constant oppression in the United States, it does not allow the offenders and the larger society to brush aside the claims. This shift of blame on the possibility disregards the women’s experience and strips her of credibility. A measure of that disrespect towards the women’s claims appears in the form of the term “ho” as it both demonizes her and attempts to make the male figure more sympathetic (try to make it seem as if she was the one with the power in the situation rather than the reality). These arguments give figures like R. Kelly, Myke Tysons, and Charlamagne the god a benefit of the doubt as many individuals cannot see them as truly doing this act. Within these narratives, the idea that they are “victims of their environment” also appear at the benefit to the male offenders. While environment always has an influence on one’s behaviors and actions, it should never be used to completely ignored the reality of the situation especially in cases where it is a repeated offense.

In treating young Black girls more adult-like than their peers, many of them are seen as needing “less protection and nurturing,” especially in comparison to their white counterparts. Not only are they given less resources and care, but they are also hypersexualized, seeing as they are viewed as “ready” or “almost ready,” despite them being young girls. This is especially dangerous when it comes to men taking advantage of young Black girls because they know the repercussions will not be as severe. Cottom discusses how the legal system already has little concern for women who report sexual assault, and how that adds to the already miniscule amount of concern there is for young Black girls when they are seen through the “expectations of an adult.”

Though Black men do face extreme oppression, the argument that “Black men are too oppressed to oppress” is very problematic and dangerous in that it allows them to sexually harass Black women with little to no repercussions. Cottom uses examples of Black men of high statuses, but also adds that Black women are “most vulnerable to the men in [their] homes,” where they are more likely to blame themselves. At the end of chapter 7, she says that in having the burden of protecting Black men, Black women are often trapped in being silent when it comes to gender violence within their communities, which is also apparent in Black communities defending celebrities like R. Kelly and Mike Tyson.

The hypersexualization and adultification of young black girls have a long history in America. This treatment by peers and adults robs black girls of their childhood. It discourages mistakes that most children are bound to make. Stereotypes, expectations, and questions involving morality are forced upon their young shoulders. As if being black and a female is not enough, they must also face the struggle that comes with hypersexualization. Black girls and their moms must constantly worry about how young black girls and their bodies are perceived. Cotton discusses a situation in which there were two moms taking their young daughters to the pool. One child was black and the other was white. The white child only had bottoms on because the mom argued that since they are only four, it should not matter. However, the black child had a two-piece on that did not reveal any of the child’s skin. The white mom did not understand this even after the black mom tried to explain. The reason behind the black mom’s decision was not revealed until they got to the pool and people commented on how her child already appeared to have a curvy body. In other words, this treatment causes black girls to potentially feel bad about their bodies and shrink into themselves or it can lead to them becoming very sexual at a young age due to the stereotypes that are forced upon them. Such stereotypes leave black girls to be more susceptible to sexual assault which potentially could be disputed on the basis of the idea that the little girl was “fast”.

Thank you for sharing the article from Georgetown Law–I found it really informative on the topic of the adultification of young Black girls and the resulting erasure of childhood. One quote I wanted to pull out is on page 6: “Ultimately, adultification is a form of dehumanization, robbing Black children of the very essence of what makes childhood distinct from all other developmental periods: innocence. Adultification contributes to a false narrative that Black youths’ transgressions are intentional and malicious, instead of the result of immature decision-making–a key characteristic of childhood.” I thought the data from the study conducted and its corresponding data visualizations were compelling. Across all ranges, researchers found that participants viewed Black girls collectively as more adult than white girls. Beginning as early as 5 years of age, Black girls were more likely to be viewed as behaving and seeming older than their stated age. These results directly suggest that adultification is a contributing factor to the harsher treatment of Black girls when compared to white girls of the same age: including the “disproportionality in school discipline outcomes, harsher treatment by law enforcement, and the differentiated exercise of discretion by officials across the spectrum of the juvenile justice system.” The consequences of the erasure of childhood for Black girls also extends to the child welfare system–“Authorities in this system who view Black girls as more independent and less needing of nurture and protection may assign them different placement or treatment plans from white girls.” This study helps to bring awareness and attention to the phenomenon of adultification.