Many people, especially those familiar with hip hop, would be surprised to learn how common it is for prosecutors to introduce rap lyrics as evidence in criminal trials in order to establish a defendant’s proclivities toward illegal behavior. Although people who listen to rap understand full well that the lyrics are intentionally hyperbolic and often purely fictitious, that’s not how they are presented to juries.

Last year, a Maryland appeals court ruled that Justin Hannah, who had been convicted of attempted murder, was entitled to a new trial because prosecutors incorrectly used some of his rap lyrics against him (Hannah v. State of Maryland). However, it is far more common for lyrics to be allowed at trial, and attempts to appeal their use are usually unsuccessful. According to Andrea Dennis in “Poetic (In)Justice? Rap Music Lyrics as Art, Life, and Criminal Evidence,” the result is that defendants may face a prejudiced jury. When courts permit prosecutors to admit rap music lyrics as criminal evidence, says Dennis, “they allow the government to obtain a stranglehold on the case,” at least in part because “[t]he admission of defendant-composed lyrical evidence plays on the biases of jurors against rap music and those who listen to or associate themselves with rap music.” (See also Stuart Fischoff’s 1999 article “Gangsta’ Rap and a Murder in Bakersfield.”)

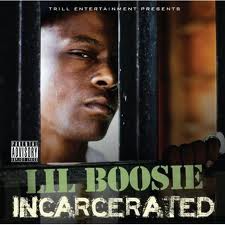

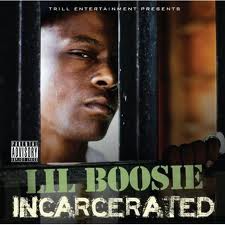

In April, Lil Boosie (already in jail on a drug conviction) will stand trial for murder in Louisiana, and it appears as if prosecutors will use his lyrics against against him. The stakes here are particularly high, and so this is a case that hip hop fans, performers, and scholars alike should be paying close attention to for the obvious issues it raises about free speech, not to mention our ideas about what role art should have in our society.

Here’s a question: Are there any circumstances in which rap lyrics should be admitted as evidence?

It’s not news, but I couldn’t resist posting this review of a Mac Miller concert from a couple of months ago. Funny stuff. In it, Chris Richards (the astute music critic at the Washington Post) proclaims Miller’s Silver Spring concert the worst of the year. I wrote to Richards thanking him for the review the day it came out.

It’s not news, but I couldn’t resist posting this review of a Mac Miller concert from a couple of months ago. Funny stuff. In it, Chris Richards (the astute music critic at the Washington Post) proclaims Miller’s Silver Spring concert the worst of the year. I wrote to Richards thanking him for the review the day it came out.