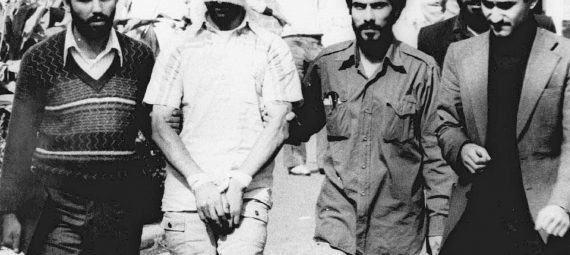

On November 4th, 1979, a group of Iranian university students and Islamist radicals seized the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, taking 65 Americans hostage. The students were motivated by U.S. President Jimmy Carter’s decision to permit the entry of Reza Pahlavi, into the United States for cancer treatment in New York. Pahlavi was the last Iranian Shah who was deposed by the 1979 revolution led by the Islamist cleric Ayatollah Khomeini. Khomeini endorsed the militant action to shame the United States for their inference in Iranian affairs and to bolster Iranian support for his Islamist Republic. The captors vowed to release the hostages only in the event that Carter return the Shah, to be tried for his crimes against Iranian people during his “reign of terror.” Carter’s diplomatic negotiations with Iran’s anti-American government failed to get more than 13 hostages released, and the Iranian captors continued to humiliate the United States before the world for 444 days until the end of Carter’s administration on January 20th, 1981.

The seizure of the US Embassy by the Islamist rebels marked Iran’s political and cultural break from the Shah’s secularist reign and the climax of Iranian resentment of U.S. incursions on Iranian sovereignty, which had festered since the 1953 CIA-orchestrated coup that deposed Iranian premier, Mohammed Mosaddegh. After the coup, Reza Shah Pahlavi imposed a military dictatorship that worsened domestic unrest and amplified disapproval of the US’ extended meddling in Iranian affairs. Iranian Islamists and other radical groups began publicly condemning the Shah’s secularist and modernizing agenda, specifically his enactment of the White Revolution program, a series of social and economic reforms. In response to growing Islamic unrest, the Shah’s secret police force (SAVAK), established with the help of the CIA, tortured and killed thousands of Islamic clerics and other dissidents. Despite the Shah’s explicit human rights violations, the domino theory and the pervading US Cold War foreign policy strategy of containment justified prolonged intervention in Iranian local politics, and the US continued to support the Shah’s regime through astounding financial, economic, and military contributions for over a quarter-century.

While the US-backed Shah wreaked havoc within the country, a revolutionary movement led by the Iranian Shi’i cleric Ayatollah Khomeini intensified. Khomeini unified Iran’s factions through Islamic rhetoric, which paralleled the rise in radical Islamism in neighboring Arab countries. After the Shah fled the country in exile, Khomeini returned to Iran in February of 1979 to construct a new, independent Islamic Iran and denounced the United States for its role in the Shah’s “reign of terror.” The November 1979 hostage crisis demonstrated the success of Khomeini’s mobilization of the Iranian people to take militant action against the enemies of Islam, which he identified to be the Shah and the United States. By November 1979, Iran’s anti-American stance had hardened to such an extent that the moralistic President Carter could not crack. Instead, Carter’s protection of the Shah within US borders was seen as a contradiction of his espoused human rights commitments. For the Iranian leaders and the Islamist captors, diplomatic negotiations with the US were off the table, and they would settle for nothing less than the American turn-over of the deposed Shah.

Coverage of the November 4th crisis by the New York Times exaggerated the anti-American sentiments in Iran and demonstrated critique of Carter’s rejection to return the Shah. The front page of an issue released on November 5th, 1979 exposed the powerful religio-cultural motivations behind the hostage situation. The Iranian students were empowered by revolutionary struggle and continued endorsements by Iranian religious leaders to engage in militant action against the “imperialist [U.S.] embassy.” The New York Times provoked an image of a merciless and relentless Khomeini who “hoped reports that the Shah was dying of cancer were true,” and thus would remain unwavering in his demand for the U.S. to return the Shah. The headlining article of the New York Times issue released the following day on November 6th described Carter’s faith in the Iranian government to aid in the release of the Americans, a huge underestimation of the powerful anti-American rhetoric employed by revolutionary leaders in their long struggle towards an Islamist Iran. The article stated that “the real power in Iran lies more with Khomeini,” and thus, it would have been a wiser decision for the US to concede to the Islamist cleric’s aggressive demand for the return of the Shah. While the New York Times did not offer enthusiastic support of Carter’s rejection, it did attempt to ease anxieties of Iran’s threat for an oil embargo and bolster the U.S. economic position. Despite Carter’s rejection of the Shah’s demands, the effects on the economic landscape back home would not be catastrophic. Nonetheless, the rejection to turn over the Shah perpetuated questions of Carter’s judgment and moral character. Carter’s decision to protect one Iranian life over 52 Americans lives, not only cost him reelection, but it also cost the U.S. any chance for a reconciliation with the new Islamist Republic whose people cried for the “Death of America.”

Works Cited

Craig, Campbell, and Fredrik Logevall. America’s Cold War: The Politics of Insecurity. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020.

“Iran Leaders Back U.S. Embassy Seizure,” New York Times, 06 Nov 1979: A1

Saikal, Amin. “Islamism, the Iranian Revolution, and the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan.” In The

Cambridge History of the Cold War, Eds. Melvyn P. Leffler and Odd Arne Westad, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010: 112-134.

“Tehran Students Seize U.S. Embassy and Hold Hostages,” New York Times, 05 Nov 1979: A1

“U.S. Rejects Demand of Student in Iran to Send Shah Back,” New York Times, 06 Nov 1979: A1