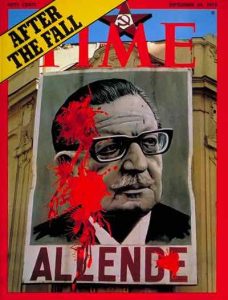

On Sept. 11, 1973, a military-led coup by General Augusto Pinochet seized the Chilean government and established what would be a nearly decade-long junta dictatorship. The siege succeeded a well-established democracy in Chile led by then-President Salvador Allende, a democratically-elected Marxist. In light of Allende’s demise and the rise of Pinochet’s dictatorship, scholars have observed U.S. involvement in the junta’s siege to advance its Cold War agenda against Communism and the Soviet Union.

During the three years Allende led Chile, the country struggled through economic hardship and domestic political polarization. Yet, evidence suggests that the United States’ aversion to communism in light of the Cold War also contributed to the junta’s coup. Chile’s transition to a socialist government under Allende arrived despite historical ties between the United States and Chile. Since the 1950s, Allende has been outspoken against the United States, particularly regarding its actions in Guatemala. Allende was not alone; he reflected a growing resentment toward the U.S. from Chileans. Chile’s straddling of democracy and socialism sheds light on the county’s decision to circumvent the United States’ pervasive commitment to keep left-leaning ideology out of the Americas. Its socialist government also reflected a newfound, tense relationship between the two countries, which lead to the United State’s support of Pinochet’s junta coup and regime.

Chile’s democratic election of Allende angered the Nixon administration, ultimately moving the administration to intervene in Chile. U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger said in 1970 that he didn’t “see why we have to let a country go Marxist just because its people are irresponsible.” Although Allende was elected democratically by Chilean citizens, Kissinger found that his election was wrong. The idea that an educated and sophisticated country would choose a different path was deeply upsetting. The release of declassified FBI and CIA documents suggests that the Nixon administration created a series of operations to economically undermine Allende’s regime and ultimately support the overthrow of the Chilean government in 1973 altogether.

Newspapers such as The New York Times covered Pinochet’s coup and linked its coverage of the junta’s siege to U.S.-Chilean diplomatic relations. The Times reported on September 13th that the US government knew about a potential military coup but did not stop it. The Times did not only cover statements made by the White House regarding its involvement in the coup but reported statements from political leaders worldwide. On September 15, The Times quoted President Tito of Yugoslavia, who said that the United States “had instigated ‘hireless generals’ to overthrow and murder President Salvador Allende Gossens of Chile… Yugoslavia must be alert, he said, to apprehend agents and spies infiltrating the country to foment disunity.” The Times coverage of Tito and the siege itself creates connections between the United States and the Chilean coup, indicating that the United States was potentially involved in Allende’s demise.

There are also components external to Cold War politics that may have persuaded the United States to support the military coup. Scholars Campbell Craig and Fredrik Logevall observe economic variables that may have heightened U.S.-Chilean diplomatic relationships. When Allende was president, he “moved swiftly to break Chile free of its domination by large landholders and American multinational corporations. He nationalized nearly $1 billion of U.S. investment. Nixon and Kissinger reacted aggressively… This worried them in terms of geopolitics, but also on the domestic front,” according to Craig and Logevall. Although it would be incorrect to concretely state to what capacity the United States invested itself in Pinochet’s military coup, Craig and Logevall shed light on the financial barrier that Chile’s leftist regime created for the United States. Chile’s shift to socialism created political and economic tensions between it and the United States during the Cold War, which were ultimately alleviated by Pinochet’s military dictatorship.

Work Cited

Bernard Gwertzman. “U.S. Expected Chile Coup but Decided Not to Act: Instructions to Embassy U. S. Expected a Military Coup in Chile the Ambassador’s Trip.” The New York Times, Sep 14, 1973: 81.

Craig, Campbell and Fredrik Logevall. America’s Cold War: The Politics of Insecurity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 2009.

Jervis, Robert. “Identity and Cold War.” In The Cambridge History of the Cold War, edited by Melvyn P. Leffler and Odd Arne Westad. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010: 22-43.

Kornbluh, Peter. “Chile and the United States: Declassified Documents Relating to the Military Coup, September 11, 1973.” NSA Archive at George Washington University. 2001.

Raymond H Anderson. “Tito Hints that U.S. is to Blame in Chile: Soviet Accuses ‘Imperialism’ Role for Nonaligned Sought Italy’s Reaction Strong.” The New York Times, Sep 15, 1973: 10.