Japan, 1971

After World War II, Japan’s economy grew at an unprecedented rate, becoming the world’s second-largest economy by the end of the Cold War. A long history of well-informed decisions by the Japanese and United States drove this change. Perhaps the most revolutionary change, however, was the decision to move the Yen to a floating exchange rate on August 15th, 1971. The Yen switch to a floating exchange is an economic decision that was entirely dependent on Cold War events such as the Bretton Woods conference and the Vietnam War.

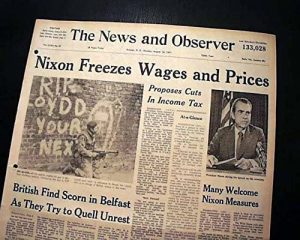

In July 1944, delegates from 44 countries met in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. They agreed on the Bretton Woods system which established an adjustable pegged system, based on gold, to value international currencies. The Japanese Yen for instance was pegged at a set rate of 360 per $1. The deal reflected the United State’s economic global dominance after the war. Nations used the U.S. dollar as a reserve currency rather than scarce gold and the value of the dollar single-handedly moved world economies. As long as the United States. was able to maintain price stability, the adjustable peg system worked. The Vietnam War made this impossible, however. As government spending under the Johnson and Nixon Administrations skyrocketed, so did inflation, and the U.S. dollar became overvalued compared to gold. By the 1970s, foreign nationals held billions of dollars and began redeeming them for American gold. In August of 1971, Nixon instituted the first price controls since World War II and closed the gold window, stopping the exchange of dollars for gold. Two years later the fixed exchange rate system ended and was replaced with a floating exchange rate system.

For decades, Japan was a passive acceptor of the Bretton Woods system, but in 1971, currencies like the Yen followed the dollar and became undervalued as well. Japan’s imports were far too expensive, and their exports were too cheap. Without a fundamental change to the FOREX market, Japan faced crippling deficits putting 30 years of economic growth at risk. In August of 1971, President Nixon announced the end of the classical gold standard at Camp David, effectively making the Yen, and other world currencies, floating. The shift to a floating exchange rate propelled Japan to a new level of international relevance. The internationalization of the Yen essentially forced Japan to integrate its capital markets with the world economy, thus establishing itself as a major player on the world stage. In 1975, Japan’s influence became clear when it joined the Group of Seven.

It was widely recognized that having a floating exchange rate allowed nations like Japan to grow their status in the world economy. In his November 1971 article Japan in Europe, Clyde Farnsworth notes that Japan “has acquired such dimensions that its influence in the world economy is anything but negligible.” Farnsworth’s article proved to be correct. Japan has continued to integrate into the world economy, and brands like Sony and Toyota dominate their respective global markets.

Bibliography

Bordo, M. D. (2020). The imbalances of the bretton woods system 1965 to 1973: U.S. inflation, the elephant in the room. Open Economies Review, 31(1), 195-211. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11079-019-09574-2

Belke, Ansgar, and Ulrich Volz. “The Yen Exchange Rate and the Hollowing Out of the Japanese Industry.” Open economies review 31, no. 2 (2020): 371–406.

Frances McCall Rosenbluth, and James Sundquist. “Japan and the Collapse of Bretton Woods.” In Bretton Woods Agreements, 236. Yale University Press, 2019.

By CLYDE H. FARNSWORTH. (1971, Nov 28). Japan in europe: Export efforts progress slowly in Europe. New York Times (1923-Current File) Retrieved from http://newman.richmond.edu:2048/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/japan-europe/docview/119146451/se-2?accountid=14731