On January 3, 1961, then-President Dwight Eisenhower broke diplomatic relations with Cuba, using the United States’ dominance in the global arena to deter Communist influence within the Western Hemisphere. Eisenhower’s actions cultivated more than half a century of hostility between the U.S. and Cuba and contributed to creating the Bay of Pigs invasion.

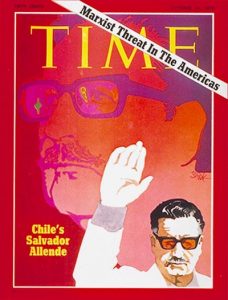

Yet, Chilean Senator and Eventual President Salvador Allende sent a telegram to then-Ambassador Juan José Diaz del Real of Cuba within days of Eisenhower’s actions, confirming the Socialist Party of Chile’s commitment to diplomatic relationships with Cuba. Allende’s telegram arrived despite the United States and Chile’s historic diplomatic and pro-democracy ties. The United States’ diplomatic shift also created fissures between then-democratic Chile and the United States. Chileans reinforced its relationship with Cuba, foreshadowing Chile’s ultimate transition to a socialist government in 1970.

In 1944, scholar Mark Philip Bradley noted that only five Latin American states, including Chile, could call themselves nominal democracies. Yet, in three short years, dictatorships throughout the region fell as popular democratizing forces were mobilized. Scholars such as Campbell Craig and Fredrik Logevall observed that Chile was a model democracy in Latin America from a U.S. foreign policy perspective. In 1958, Chilean President Jorge Alessandri’s pro-U.S. regime supported the United States’ decision to break ties with Cuba, The New York Times wrote.

Nevertheless, in the 1950s, socially democratic populist and progressive movements came to power, such as the Socialist Party of Chile. Allende ran for president in the 1958 election against Alessandri and lost to Alessandri by only 40,000 votes, according to The Times. Chile’s straddling between democracy and socialism reflects a more significant polarization throughout Latin America due to its evolving political climate. Although countries can be both democratic and socialist, the United States’ Cold War policy assumed Latin American countries should accept capitalist “reforms to alleviate economic and social conditions that facilitated the spread of communism,” historian Stephan Streeter wrote. Further, in a March 1961 speech to the Corp of Latin American Republics, a couple of months after Eisenhower decided to break diplomatic relations with Cuba, President John F. Kennedy said that the United States would reaffirm its pledge to defend any American nation that succumbs to communism. He encouraged Latin American countries to avoid engaging with leftist ideology. Socialist movements in Chile and Latin America reflected a rise in socialism across other decolonized regions post-World War II, such as Asia and the Middle East.

Newspapers such as The New York Times covered Allende’s publicized telegram to Cuba in the context of Chilean politics. According to The Times, Allende was explicit in his fervent commitment to Castro. In the article, Allende’s telegram was even quoted: “‘The popular forces of [the front] maintain their incorruptible promise to defend Cuba in case of attack.’” The Times depicts the Socialist Party’s commitment to social ideals rather than U.S. allyship. Further, The Times’s article can also indicate areas where the newspaper critiqued the U.S. Although this is one article out of The Times’s Chile coverage, it does suggest that not all Chileans supported democracy and Chile’s diplomatic relations with the United States.

Some may deign why Allende’s telegram and Chilean-U.S. relations were essential to the U.S. Political scientist Robert Jervis acknowledged Latin America’s pivotal role in the Cold War in strengthening the U.S.’ promotion of democracy worldwide. Unlike traditional European politics that dominated the world as recently as World War II, Jervis wrote that a balance of power might temporarily yield peace and security. Still, the world could be made safe for democracy for the United States or communism for the Soviet Union only if it became dominant if not universal throughout the world. U.S. officials ultimately preferred short-term inequality and political unrest if it meant that ultimately the preferred political system, democracy, would be put in place for the long term. Chile’s commitment to democracy was thereby crucial to the U.S. because the country’s political system was essential to the U.S.’s long-term foreign policy to promote democracy in the global arena.

Work Cited

Bradley, Mark Philip. “Decolonization, the Global South, and the Cold War, 1919–1962.” In The Cambridge History of the Cold War, edited by Melvyn P. Leffler and Odd Arne Westad. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010: 464–85.

Craig, Campbell and Fredrik Logevall. America’s Cold War: The Politics of Insecurity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 2009.

De Onis, Juan. “LATINS RESISTING BREAK WITH CUBA: Chile, Facing Challenge by Leftists, Seeks to Show Independence of U.S.” The New York Times, January 1961: 8.

Jervis, Robert. “Identity and Cold War.” In The Cambridge History of the Cold War, edited by Melvyn P. Leffler and Odd Arne Westad. New York: Cambridge University Press 2010: 22-43.

Kennedy, John F. 1961. “Address at a White House Reception for Members of Congress and for the Diplomatic Corps of the Latin American Republics.” JFK Library. March 13, 1961.

Streeter, Stephen M. “Nation-Building in the Land of Eternal Counter-Insurgency: Guatemala and the Contradictions of the Alliance for Progress.” In Third World Quarterly 27, no. 1, 2006: 57–68.