< Previous | Funk and “Let’s Get It On”

In 2001, Motown reissued Let’s Get It On as a two-disc deluxe edition release, with remastered versions of the original recordings and previously unreleased demonstration recordings. The changes between the demo and the final release of the song illustrated the influence of Marvin Gaye’s vocal performance and lyrical changes on the overall tone of “Let’s Get It On.” Through his vocal composition, Marvin Gaye not only transformed a spiritual ballad into a corporeal, sex call but also pioneered the genre of hyper-sexual soul.

Singer/songwriter Ed Townsend worked as a co-producer and songwriter on “Let’s Get It On.” He originally conceived the idea for the song after completing rehab. • Image source: Secondhand Songs (original unknown).

The most notable difference between the demonstration recording and the final version of “Let’s Get It On” is the lyrical changes. Music producer Ed Townsend conceived the idea for “Let’s Get It On” after completing rehabilitation for alcoholism (Flory 2010; Jackson 2002). As a result, his original lyrics, which occur in the demo vocals, use the phrase “let’s get it on” as a motivational call to “move on” with life after struggle. The lyrics of the verses speak of the need for peace, love, understanding, and brotherhood, and the chorus refers to a collective “we.” Gaye altered the perspective of the song for the finished version, transforming the hook “let’s get it on” into a sexual innuendo, and including in the lyrics a woman who is the object of his desire.

Drawing on traditions from funk and soul, throughout the final version of “Let’s Get It On” Gaye uses double entendres to approximate physical and religious imagery (McClary 1991). In the extended chorus and improvisation towards the end of the song, Gaye urges the listener to give in to the “spirit,” however the sexual overtones of the music and the religious allusions in the lyrics make it difficult to determine if he is referring to the sexual spirit or the Holy Spirit. In the improvised sections at the end of the song, Gaye again uses religious erotic imagery when he declares that he’s “been sanctified” by his encounter with the woman he is speaking to.

Taken on Feb. 27, 2011, this photo of a church service at Pentecostal Tabernacle in Cambridge, Mass. showcases the experience in Pentecostal services. The mass focuses on spiritual embodiment and release that is similar to sexual experiences of climax. • Source: AP Photo/Winslow Townson

The semiotic connections between religious and sexual ecstasy are evident in the black Gospel church, especially in the Pentecostal church in which Gaye was raised. The structure of Pentecostal religious services ironically and unconsciously mirrors sexual experiences and allows for sexed experiences of the divine that are often contradictory to the denomination’s conservative policing of bodies and sexual practices (Nadar & Jodamus 2019). Gaye’s blending of sex, love and religiosity, therefore, suggest that “Let’s Get It On” marked Gaye’s sexual liberation from the conservative religiosity that shaped his childhood. Furthermore, Gaye’s lyrical alterations are accompanied by a vast amount of sexual energy, which he conveys through his vocal performance.

The primary way in which Gaye infuses sexual energy into his vocal performance is through strategic changes in the timbre of his voice. In the final version of “Let’s Get It On”, Gaye alternates between a high falsetto and strong, soulful belting to add grain to his vocal performance and aurally relay a sexual encounter. For example, in the introductory measures of the final version, his ad-libs are surprisingly soft and tender, drawing a stark contrast to the low growl of “let’s get it on” and the passionate declaration that he’s “been really trying…to hold back this feelin’ for so long.” A common technique among soul singers, grain is the “emotional and erotic expressiveness of the voice” and is often used to convey the pleasure and pain of intimacy (Mercer 1993, p. 93). At different points in “Let’s Get It On”, Gaye changes his vocal timbre to convey the tenderness and passion of the potential sexual encounter.

The sensuality of Gaye’s performance is also augmented by his use of timing. In the final version, Gaye drags many of his words, building the listener’s anticipation and the sexual tension of the song. His use of timing to add tension to the music is evident from the very beginning. While the opening lines of the demo version are introduced after an extended quarter rest, the final version begins after a half rest (Flory 2010, pp. 76 -77). Although only half of a beat longer, after the sensual introductory wah-wah notes, the increased rest time draws the listener to the edge of their seat in anticipation of what happens next.

At times when Gaye does fill the anticipatory gaps in the music, he does so with wordless sounds and grunts which allude to sexual activity and exertion. A notable difference between the demo and final versions of the song is the lack of the extended instrumental ending (~2:50 – 5:00 min), which Gaye fills with his improvised spiritual sensuality and pleasure-filled groans in the final release.

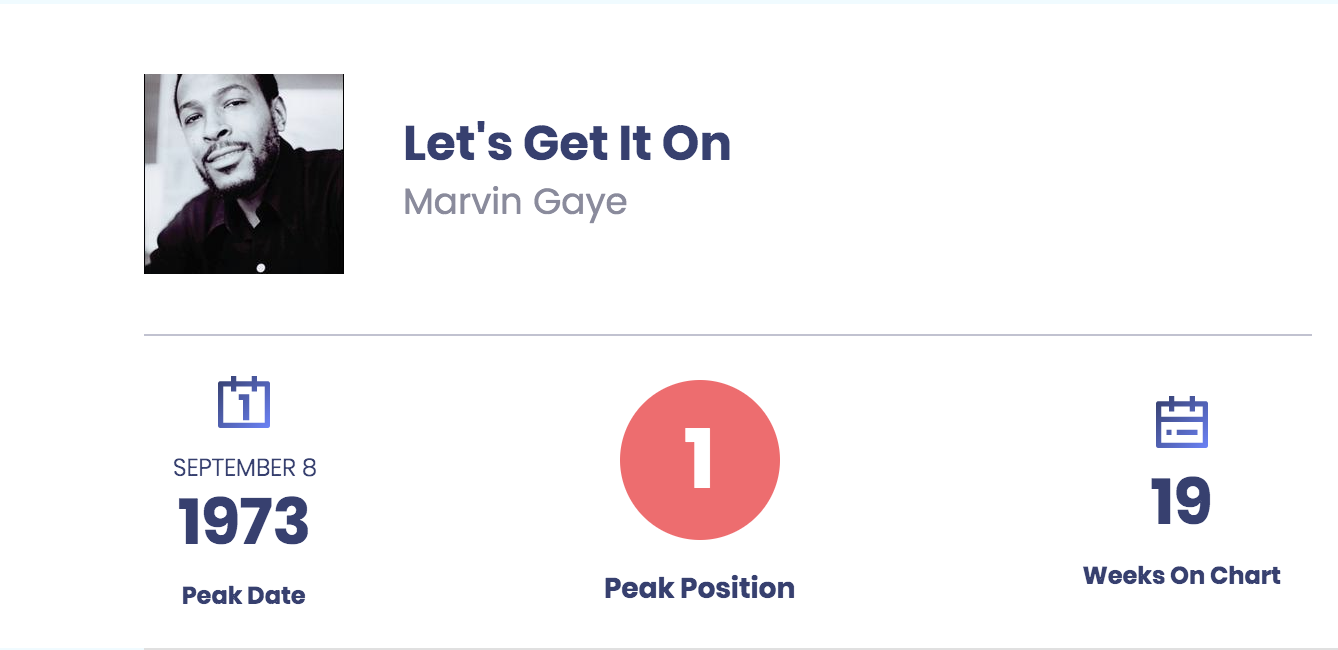

Although the musical composition of the demo and final versions of “Let’s Get It On” are identical, Gaye’s lyrical changes and sensual vocal performance completely transform the song’s mood from a hopeful, uplifting anthem to a corporeal declaration of sexual desire. The crossover commercial success of the final version, which peaked at number 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart (Billboard, n.d.), and the song’s lasting impact on the music industry, speak to Gaye’s talent as a vocal composer.

Billboard performance history of “Let’s Get It On.” • Source: Billboard (n.d.)

Next | Impact of “Let’s Get It On” >