American musicologist and Motown expert, Andrew Flory (2010) was among one of the first scholars to explore Marvin Gaye’s work as a vocal composer. In his analysis of Gaye’s use of documented improvisation in the songwriting process, Flory uses the term “vocal composition” to acknowledge “Gaye’s ability to blur the lines between performing, recording, and composing” (p. 65). Through a historical analysis of Gaye’s career and recordings, Flory argues that Gaye’s use of vocal composition is fundamental to understanding both Gaye and his work. An individualist technique, vocal composition is often seen as the antithesis to Motown’s traditional streamlined sound. Therefore, Flory tracks Gaye’s professional and personal divergence from traditional Motown aesthetics with the creative evolution of his vocal composition techniques.

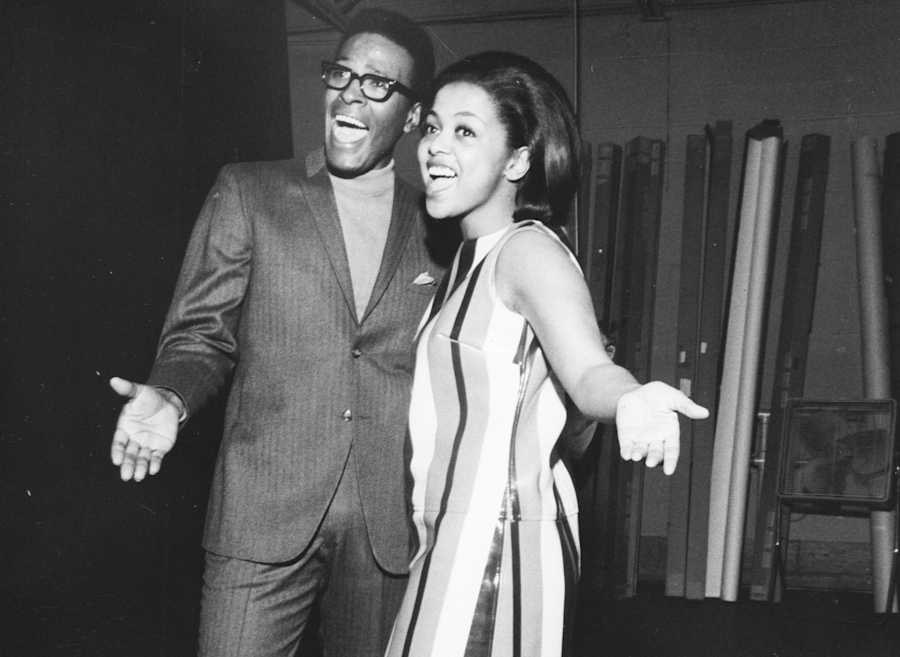

Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell. • Photo by Gillard Petard via Getty Images.

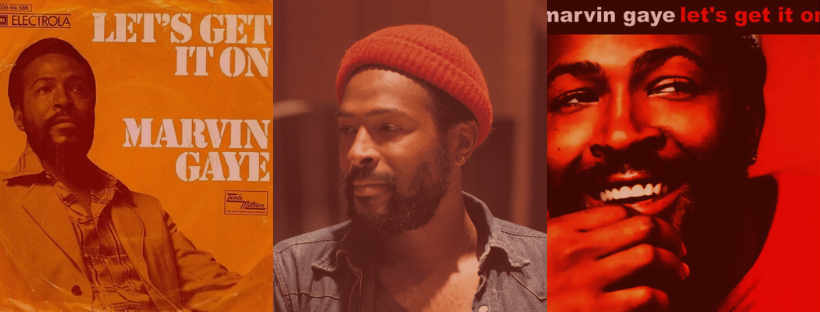

Recorded in the spring of 1973, the making of Let’s Get It On marked a time of exploration in Gaye’s personal and professional life. After moving to Los Angeles in 1970, Gaye was estranged from his wife, Anna Gordy, and the tensions in their union only exacerbated the hostility between Gaye and Motown Records, which was headed by Gordy’s brother (Marre 2005). Since the death of his duet partner Tammi Terrell in 1970, Gaye’s relationship with Motown had grown tenuous. Terrell died of complications from a malignant brain tumor that Motown initially downplayed in order to market the duo’s new material (History.com, 2009). Affected by her death and Motown’s insensitivity, after Terrell’s death Gaye stopped performing live for the next three years– until he released Let’s Get It On. For this reason, scholars like Flory and Michael Eric Dyson (2008) believe that Gaye’s sensual vocal performance on “Let’s Get It On” was a rebellion against the containment of his musical and sexual spirit, which was building from his childhood, through his relationship with Motown, and then his marriage to Anna Gordy.

Other scholars have different interpretations of the shift in Gaye’s music. In his historical analysis of What’s Goin’ On (1971), Trouble Man (1972), and Let’s Get It On (1973), Mark Anthony Neal (1998) argues that Marvin Gaye’s trilogy of early 1970s recordings aurally documents the demise of the black protest movement. On the heels of What’s Goin’ On, which Neal refers to as the “quintessential black protest recording,” Neal contends that Gaye’s conscious step away from social protest media with Trouble Man and Let’s Get It On was a manifestation of state-sponsored violence against black progressives in the post-King civil rights era. This violence, Neal argues, created inter-class conflict within the black community that could have harmed Motown’s crossover ability had the label’s artists, which included Gaye, continued to produce overtly political music. To Neal, Gaye’s foray into hypersexual soul represented his acceptance of the hypersexualization of black men in the Blaxploitation era, in order to appeal to white audiences.

Marvin Gaye’s three 1970s album releases (L to R): What’s Going On (1971), Trouble Man (1972) and Let’s Get It On (1973). • Sources: One Music API

Either way, “Let’s Get It On” was a widely successful single and has had a lasting impact on the way intimacy is represented in music. Neal (2004) identifies Gaye as one of the artists who normalized expressions of the private and intimate aspects of black life and culture in the full view of the marketplace. In the aftermath of Let’s Get It On, lots of other artists changed their music in the direction of hyper-sexualized soul. Smokey Robinson’s A Quiet Storm (1975) and Major Harris’s 1975 classic “Love Won’t Let me Wait,” both contained sensual lyricism and instrumentation reminiscent of “Let’s Get It On” (Neal 2004). And more recently, Gaye’s influence has also been linked to the musical style and performance techniques of more contemporary artists like R. Kelly and Chris Brown (Neal 2004; Singersroom 2011).

Rapper Drake’s second studio album, Take Care (2011), features a song called “Marvin’s Room,” which describes a tumultuous romantic relationship. • Image credit: John Salangsang/Shutterstock

Even artists outside of R&B and soul have been influenced by Marvin Gaye’s representation of sexual desire and intimacy. Gaye’s legacy as a sex symbol has become so ubiquitous that mention of the artist’s music alone serves an allusion for sexual encounters. From rappers Drake and Big Sean to pop singers like Charlie Puth, numerous artists have made references to Marvin Gaye in their music. Big Sean’s 2011 release of “Marvin & Chardonnay” featuring Kanye West and Roscoe Dash peaked at number 1 on the Billboard R&B charts.

Speaking to the importance of “Let’s Get It On” to Gaye’s legacy, other hit songs specifically reference the 1973 single. For example, a line in the chorus of pop duo MKTO’s 2013 hit “Classic” says “let’s get it on like Marvin.” The chorus also strikingly places ”Let’s Get It On” in the company of other classic hits like Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” (1982) and Prince’s “Kiss” (1986). Similarly, in 2015 Charlie Puth and Meghan Trainer released their duet “Marvin Gaye,” with the hook “let’s Marvin Gaye and get it on/ you got that healing that I want.”

Marvin Gaye (ft. Meghan Trainor) – Charlie Puth (2015) • Uploaded by Youtube/CharliePuth