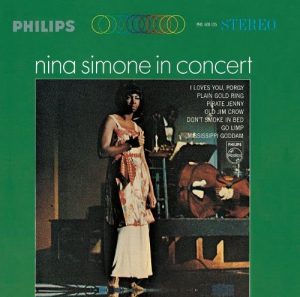

Nina Simone In Concert, the first for Nina Simone under the Phillips label, is a recording of her March and April 1964 performances in Carnegie Hall, and features Simone on both vocals and piano, backed by a small ensemble of bass, upright bass, drums and guitar. Carnegie Hall in New York City has historically been considered the peak of sophistication in European-style classical music. This live album, along with the prior live album recording in 1963 in Carnegie, is performed in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement, marking a sharp artistic turning point in Nina Simone’s career (Brun-Lambert 101). As Simone states herself, “After the murder of Medgar Evers, the Alabama bombing and ‘Mississippi Goddam’ the entire direction of my life shifted, and for the next seven years I was driven by civil rights and the hope of black revolution” (Simone 91). Consequently, songs that appear on In Concert are often only considered through the perspective of Nina Simone, the African-American Civil Rights activist. However, her activism, which she discusses in her autobiography, is also a musical resistance against unfair musical categorization.

The album consists of 7 tracks, two of which I will analyze musically to support my argument (“Pirate Jenny,” and “Mississippi Goddam”). Both tracks portray anger musically, either through subjective, isolating vocal performances and a manipulation of classical piano techniques. Author David Brun-Lambert speaks of the anger in Simone’s performance as such: “More direct, rougher, more brutal than the concert recorded at Town Hall, a complete break from the sophistication of Nina at Carnegie, this first record for Phillips was a taster of a radiant and unpredictable artist” (129). The album is politically and racially motivated, but there are also musical elements that unpredictably defy her audience’s expectations, proving that female black musicianship is more than being considered just a “jazz singer”.