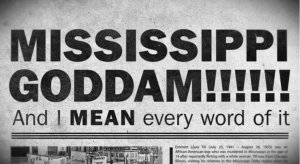

Understanding how Nina Simone’s audience and critics responded to her 1964 performances in Carnegie Hall underlines my argument because it places Nina Simone’s work in context with the Civil Rights movement occurring in the early 1960s, as well as with the entirety of her musical career. The songs that appeared on In Concert, such as “Pirate Jenny” and “Mississippi Goddam,” came to embody a politically charged direction for Nina Simone. The emergence of Nina Simone as a “Protest Singer” and activist during the onset of the freedom movement led scholar Tammy Kernodle to suggest, in retrospect, that, “By 1964 a new body of freedom or protest songs (the terms are used interchangeably) written by artists such as Nina Simone […] came to reflect these shifts (“I Wish I Knew How it Would Feel to be Free”). These “shifts” in Nina Simone’s purpose for performing, presented on lyrically politicized tracks of In Concert, also mark the beginning of Simone’s international success and popularity. Kernodle asserts that, “by 1964 her eclectic musical style […] had brought her mainstream popularity. ‘The New York press went crazy over me,’ she later wrote in her biography. ‘Suddenly I was the new hot thing.’” (“I Wish I Knew How it Would Feel to be Free”). In fact, Nina Simone’s new, directly political songs like “Mississippi Goddam” received attention, although negative, in the South, as she herself writes, “A dealer in South Carolina sent a whole crate of copies [of “Mississippi Goddam”] back to our office with each one snapped in half” (Simone 90). During these turbulent early years of the Civil Rights movement, Nina Simone found a renewed voice for her music as a form of resistance against widespread racial injustice occurring at that time, launching her image as a “Protest Singer” and anti-racist activist.

However, focusing solely on the reactions and reflections of In Concert from a political lens neglects the difficulty that audiences had in determining her musical genre. For example, international reactions to Nina Simone’s music right before her first performances in Europe in 1965 were concerned primarily with categorizing her musical sound and influences. Writer Ruth Feldstein describes that, “In discussion of Simone from around the world, fans and critics gave up on efforts to define the type of music she played. ‘She is, of course, not exactly a jazz performer—or possibly one should say that she is a lot more than just a jazz performer,’ wrote a reviewer for Down Beat” (Feldstein 1355). This confusion of genre stems from Nina Simone’s resistance to musical categorization, created by her angered vocal delivery and “classicalization” of jazz songs explained on previous pages. European and American audiences alike attempted to pinpoint exactly where to place her sound, which led to an unfortunately limited categorization that further angered Simone. Later writing in her autobiography, Simone reflects on her career at the time, specifically mentioning a performance at Town Hall just before the 1964 performance of In Concert. With discomfort, she writes, “After Town Hall critics started to talk about what sort of music I was playing and tried to find a neat slot to file it away in” (Simone 68). She writes about feeling, “as if reviewers and venue promoters were not listening to her, but rather looking at her,” seeing only her appearance as a black woman onstage (Tomlinson 45).

So why do we remember Nina Simone as a “jazz singer,” when she herself found that title to be racist and unfitting? At the time, the easiest and most marketable category for Nina Simone to fit into by the white, patriarchal music industry standards was as a “jazz singer,” thus she was promoted as such. For example, “The New York Times advertised for ‘Nina Simone, singer’ in 1961 and ‘Nina Simone, vocalist’ in 1963” (Tomlinson 60). This problematic labeling lead Nina Simone to use her anger in a dual response to Civil Rights issues and against unfair treatment as a black female musician. When applying intersectional feminist theory to this issue inspired by Audre Lorde’s article on anger, it is clear that during the 1960s, “black women musicians were not only expected to perform in the jazz genre beause of their race, but they were also expected to primarily or solely perform as singers by virtue of their gender” (Tomlinson 44). Consequently, Nina Simone’s anger, expressed throughout the In Concert live album, responds to racism as both a voice against the widespread injustices of black people in America and also a way to break free of musical categorization set up by her audience and the music industry.