The recent mass shooting of Asian women at massage parlours in Georgia has sparked outrage among the Asian-American community. This has led to a renewed interest in the study of Asian representation in the media and arts. According to Yutian Wong, ever since the popularization of Pierre Loti’s 1887 novel Madame Chrysanthéme, the trope of the Asian woman as a sexually submissive and feminine prostitute has been a well-established trope in the American popular culture. 1Wong Yutian, “Race, Sex, and Death from Miss Saigon to Atlanta,” Society and Space, March 22, 2021, https://www.societyandspace.org/articles/race-sex-and-death-from-miss-saigon-to-atlanta.Although the novel was based on Loti’s trips to Japan and China as a French businessman, much of the story was told through the filter of his own biases and preconceived imagination of an inferior Japan. This approach “served to enflame the current European obsession with Japanese culture to engender and market the exotic identity of Asian women, fueling the sexual fantasy of European men”.2Kim, Hannah. “The Madame Butterfly Controversy: Cio-Cio San’s Gender, Racial and Cultural Construction in Orientalist Metaphysics”, 125, http://yonseijournal.files.wordpress.com. n.d. Web. 11 Oct. 2014 In other words, Asian women became the objects of sexual fantasy for white men.

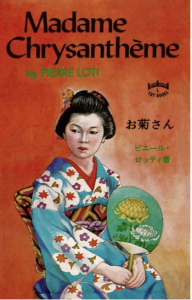

One of the covers of “Madame Chrysanthéme” (fig.1)3Fig. 1, Anonymous, 1998, Tuttle Publishing

Carmen and Madama Butterfly were created at the time when orientalism began proliferating in popular culture in the nineteenth century. As European countries and the U.S. began their colonizing mission in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia, they began to legitimize imperialism as a noble mission designed to save the people of colour. In 1854, Japan opened two of its ports to U.S. trade through the Kanagawa Treaty. The colonizers promoted the worldview that white men had the responsibility to take care of the people of color as parents are responsible for children who could become “demons without pity.” 4McClary, Susan. “Images of Race, Class and Gender in Nineteenth-Century French Culture.” In Georges Bizet: Carmen, 40. Cambridge Opera Handbooks. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139166416.004. In addition, the information obtained from scholars who were studying the subject was mobilised for “purposes of state and commercial colonization.”5Ibid, 30

Similar to Bizet’s Carmen, the Asian protagonist in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly serves as an object of desire for white men to escape from the rigidness of the existing social structure and a religious tradition that condemned sexual activity. In each of these stories, the principal Oriental characters are women of color while the main Western characters are white men. Further, both Carmen and Cio-Cio San were forced into prostitution and a “temporary marriage” by poverty and desperation. Rather than portraying the relationship between the female lead Cio-Cio San and U.S. Lieutenant Pinkerton as sexual exploitation, Orientalism seeks to present it as a consensual endeavour between adults (although Cio-Cio San was being sold along with the house for 99 cents at the age of 15).

In addition, Madama Butterfly and Carmen are organized within the “Western dichotomy between proper and improper constructions of female sexuality, between the virgin and the whore.” 6McClary, Susan. “Sexual Politics in Classical Music.” In Feminine Endings: Music, Gender, and Sexuality, 56. University of Minnesota Press, 1991. Accessed April 29, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctttt886.7. Here, exotic Carmen and Cio-Cio San are juxtaposed with their white antithesis Kate and Micaëla who are sexless and active only within the spheres of domestic life. In this context, white men who are unable to return to their true wives are essentially punished for falling prey to the lures of the exotic creatures. Don José, blinded by jealousy, stabs Carmen to death and turns himself in to the police. While Cio-Cio San is portrayed as a sexually submissive and child-like woman who is utterly devoted to her “husband”, Carmen is characterized as a femme fatale who actively expresses her sexual desire. In both operas, the sexuality and female desire of Carmen and Cio-Cio San ultimately lead to their deaths. The exotic women are both killed at the hands of a militaristic male cast.

The entrance of Butterfly is accompanied by the choir of other geishas and solo strings. Limited use of instruments is incorporated in her appearance under a Moderato tempo and a solo voice that is later built up with the complete orchestra. Puccini also includes Chinese folksongs into the musical fabric of the scores and the Japanese national anthem Kimi ga yo. In particular, the piece contains a pentanoic melody played by flutes and harp borrowed from Japanese music to create a heavenly motif. A full listing of Japanese melodies found in Madama Butterfly is featured here. The frequent use of the combination of high woodwinds with harp and bells creates an elegant and unfamiliar tone. All of these elements help create an image of Cio-Cio San as a child-like and delicate woman found in the Western sexual fantasy of Japanese geishas. Further, this affirms the myth of Asian women as being happy under white men’s sexual exploitation. In the musical number O Kami, O Kami, Japanese gongs are also included in the percussion parts to mimic the exotic Oriental sounds. In contrast, Pinkerton’s opening is more dynamic. His aria “Dovunque al mondo” is built on the notes of the “Star-Spangled Banner”, creating a strong association between Pinkerton’s character and the United States. The two movements show the disharmony between the cultures of Pinkerton and Butterfly.

In “Vieni, amor mio!”, Butterfly eagerly shows Pinkerton her personal treasures such as a mirror, a rouge, and a fan. Puccini lowers a register to portray Cio-Cio San’s seriousness as she displays the items. Yet Puccini accompanies it with the bassoon which is often referred to as the “clown of the orchestra” because of its ability to produce a bright staccato sound and a comedic quality of its low register. By doing so, Puccini creates an air of childishness surrounding Cio-Cio San, conjuring images of an infant bragging about her things.

Act 1: Vieni, amor mio!

When the second act begins, Pinkerton has been gone for three years. The most famous aria of the opera, “Un bel di, vedremo” is about Butterfly’s devotion to Pinkerton as she visualizes his reappearance. In contrast to Pinkerton’s dynamic melody, Un bel di is sung with utmost simplicity. This is sung to the most basic accompaniment in an orchestra: clarinet, harp, and solo violin. The aria includes frequent pentatonic inflections (a scale made up of five pitches) and whole-tone scales both harmonically and melodically to represent Cio-Cio San’s Japanese heritage. Several melodic motives are drawn from different folk songs, representing a type of exoticism similar to the Spanish dance rhythms in Carmen. Solo violin and muted strings mirror the opening vocal phrases where Butterfly begins to paint the picture of her husband’s return. Low strings and winds take the lead when the ship appears in her imagination; horns take the melody as she imagines guns saluting his arrival.

Madama Butterfly – ‘Un bel dí vedremo’ (Puccini, Ermonela Jaho, The Royal Opera)

The motif of Madama Butterfly is repositioned within the context of the Vietnam War through Claude-Michel Schönberg’s Miss Saigon. Miss Saigon tells a tragic love story between an American G.I. and a 17-year-old Vietnamese prostitute Kim. Ultimately, the music is an interpretation of Saigon’s fall through the Madama Butterfly myth that perpetuates the oriental stereotype created by white men. In this version, Chris is Pinkerton and Kim is Cio-Cio San. Similar to Cio-Cio San, Kim is a shy virgin who is utterly devoted to Chris. She is dressed conservatively in a traditional Asian white tunic on her first day working at the bar. Kim’s character, though not hypersexualized as the other women in Miss Saigon, does not differ much from the delicate Butterfly. Kim sings her heart out of desperation about the desire to be rescued from misery by a G.I who will bring her to the United States in the famous song “The Movie in My Mind.” Kim’s mezzo-soprano singing voice represents the young and child-like nature of a 17-year-old girl. Similar to Butterfly, Noblezada’s powerful singing under an escalating melody also represents her desperation to attain Western ideals. 7McClary, Susan. “Mounting Butterflies.” In A Vision of the Orient: Texts, Intertexts, and Contexts of Madame Butterfly, edited by Wisenthal Jonathan, Grace Sherrill, Boyd Melinda, McIlroy Brian, and Micznik Vera, 24. University of Toronto Press, 2006. Accessed April 29, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/9781442670532.6. This all presents Kim as a helpless heroine who needs an American man to save her, succumbing to the original Oriental myths. Vietnamese-American Pulitzer Price winner Viet Thanh Nguyen has characterized this musical as a “racial and sexual fantasy that negated the war’s political significance and Vietnamese subjectivity and agency”. 8Tran, Diep. “I Am Miss Saigon and I Hate It.” American Theatre, n.d. https://www.americantheatre.org/2017/04/13/i-am-miss-saigon-and-i-hate-it/.

The Movie in My Mind – Eva Noblezada

America’s bitter experiences during the prolonged Vietnam War simultaneously revived cultural images of Vietnamese soldiers as villains and filthy people. Countless war movies and musicals repeatedly invoked images of the merciless and destructive Viet Cong wreaking havoc against brave, white U.S. soldiers, disregarding the violence that American troops have sowed in the civilian communities. This includes the widespread use of Agent Orange chemicals that led to the deaths of approximately 4 million Vietnamese people and the diseases that have been carried by generations. In the musical, Kim was unable to reunite with Chris because the Viet Cong attacked Saigon. In this love story, the North Vietnamese troops were the main villains that prevented the heroine from being reunited with her Prince Charming. The American media also fails to mention that their country got involved in the war to defend the French colonial administration that had subjected Vietnamese people to violence, hunger, and deaths. Hence, it is not a random occurrence that Miss Saigon was written by a French composer.

Asian-American scholar Sunny Woan claims in her article that “the underlying cause of sexual-racial inequality between White men and non-White women is White sexual imperialism… [T]he history of Western political, military, and economic domination of developing nations compelled women of these nations into sexual submission to White men.”9Woan, Sunny. “White Sexual Imperialism: A Theory of Asian Feminist Jurisprudence.” Washington and Lee Journal of Civil Rights and Social Justice Law, vol. 13 (2008), 5 In other words, women of color have become subordinate to white men because of the social and economic consequences of Western imperialism. One example is the prison for sex workers that was built to satisfy the sexual needs of American troops during the Korean War.

As anti-Asian hate crimes are rising worldwide, we must take into consideration the voices of marginalized communities of color in our examination of musical works. In addition, we need to also critique the practice of yellowface, in which white individuals continue to misrepresent Asian characters in movies and musicals and take away job opportunities from Asian actors who are struggling to find roles that are written for them. As a Vietnamese woman of color, I cannot help but wonder why the shows that perpetuate these harmful stereotypes are still being promoted by the entertainment industry. In my personal opinion, such tropes are dangerous and offensive, especially when many Asian women are still seeking justice and accountability from a system that has repeatably harmed them.

Word Count: 1858

References

| ↑1 | Wong Yutian, “Race, Sex, and Death from Miss Saigon to Atlanta,” Society and Space, March 22, 2021, https://www.societyandspace.org/articles/race-sex-and-death-from-miss-saigon-to-atlanta. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Kim, Hannah. “The Madame Butterfly Controversy: Cio-Cio San’s Gender, Racial and Cultural Construction in Orientalist Metaphysics”, 125, http://yonseijournal.files.wordpress.com. n.d. Web. 11 Oct. 2014 |

| ↑3 | Fig. 1, Anonymous, 1998, Tuttle Publishing |

| ↑4 | McClary, Susan. “Images of Race, Class and Gender in Nineteenth-Century French Culture.” In Georges Bizet: Carmen, 40. Cambridge Opera Handbooks. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139166416.004. |

| ↑5 | Ibid, 30 |

| ↑6 | McClary, Susan. “Sexual Politics in Classical Music.” In Feminine Endings: Music, Gender, and Sexuality, 56. University of Minnesota Press, 1991. Accessed April 29, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctttt886.7. |

| ↑7 | McClary, Susan. “Mounting Butterflies.” In A Vision of the Orient: Texts, Intertexts, and Contexts of Madame Butterfly, edited by Wisenthal Jonathan, Grace Sherrill, Boyd Melinda, McIlroy Brian, and Micznik Vera, 24. University of Toronto Press, 2006. Accessed April 29, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/9781442670532.6. |

| ↑8 | Tran, Diep. “I Am Miss Saigon and I Hate It.” American Theatre, n.d. https://www.americantheatre.org/2017/04/13/i-am-miss-saigon-and-i-hate-it/. |

| ↑9 | Woan, Sunny. “White Sexual Imperialism: A Theory of Asian Feminist Jurisprudence.” Washington and Lee Journal of Civil Rights and Social Justice Law, vol. 13 (2008), 5 |