Introduction

The Phantom of the Opera, a musical written by Andrew Lloyd Webber, was adapted for film in 2004 by director Joel Schumacher. The movie follows the events that unfold in a Paris opera house in the 19th century. It is a classic show within a show styled musical that follows a love triangle between the leading soprano of the opera house, her childhood love, and the opera’s ghost, the Phantom. The childhood love, Raoul, angers the Phantom by stealing his love, Daae, leading to a plot filled with murder and suspense.2Andrew Lloyd Webber. Phantom of the Opera. United States of America: Warner Brothers Pictures, 2004. With a closer look into the fantastic score, the storyline between these characters becomes even more complex as Lloyd Webber successfully keeps the audience in suspense as he uses traditional operatic character cues in untraditional ways.

The Making of a Tragic Hero

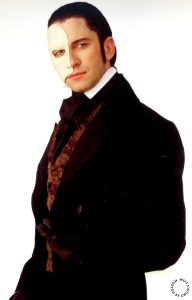

Throughout The Phantom of the Opera the audience is forced to grapple with the true intentions behind the Phantom’s actions. For much of the plot, he is seen as an evil figure in the eyes of the people of the opera house but not to everyone. Christine Daae sees the Phantom as her teacher, her angel of music that her father promised her. His voice fills the opera house to guide Christine with her musical gifts while he orchestrates the management of the house to best fit his desires. He cares for her deeply, but the audience must follow a back-and-forth between good and evil as the musical progresses. Lloyd Webber utilizes classic operatic tools to play with the subconscious of the audience. Many of the signals of good and evil within a traditional written score are combined in the characterization of the Phantom through musical signals.

The first assumption we are to make of the Phantom comes from his physical disability. For much of the musical, his face is hidden beneath a mask. We hear rumors of scarring and disfiguration beneath the mask, but truly we do not know what it is until the end. Disability within operas and films is an external tool that provides a lens into the internal makings of a character. For example, the opera Rigoletto depicts a father with a hunchback as the laughingstock, or joker, of his life. His hunchback is a tool to reinforce his mental instability within the plot because many times disability follows the cultural correlation of “disfigurement and derangement.”4Blake Howe. “Disability Studies for Musicians: An Introduction.” Music and Disability at the SMT and AMS. Music and Disability Studies at the American Musicological Society and the Society for Music Theory, November 20, 2013. https://musicdisabilitystudies.wordpress.com/2013/11/20/disability-studies-for-musicians-an-introduction/. But the audience can see the hunchback in Rigoletto, it becomes more complicated in the context of the Phantom. His true mental state is a mystery to the audience and the ever-changing music of his character does not help to clear up that mystery.

In an opera, it is common for the basses to be characterized as evil and the tenors to be the heroes that get to fall in love at the end. Subconsciously audiences can hear the difference in male leads’ voices and assume who is going to come out as good or evil as the story progresses. But Lloyd Webber wrote both Raoul and the Phantom as tenors in his musical. Both characters, if only defined by their voice, are supposed to be good. This dichotomy of what the Phantom’s music tells the audience and what his actions portray continues throughout the duration of the movie and ultimately making a tragic hero out of the Phantom.

The typical instruments that are in the Phantom’s music theme are the pipe organ, percussion, and a synthesizer. The use of these instruments usually creates a perceived darkness, power, and masculinity for his character. The percussion that is used throughout the movie is most apparent in the Phantom’s scenes for example, Raoul’s music does not usually have an apparent presence of percussion. The synthesizer, which creates an electric sound to the Phantom’s theme in different moments such as the first time he leads Daae into his lair, characterizes him in an unpredictable yet powerful way.5Andrew Lloyd Webber. Phantom of the Opera. United States of America: Warner Brothers Pictures, 2004, 00:31:00. The combination of the percussion, specifically the drum kit, and the synthesizer makes the audience see the Phantom as a loose canon—a powerful being that could be set off at any moment. On the other hand, there are moments like the Phantom’s first performance of “Music of the Night”.

This scene is one of the only scenes in which the Phantom’s music is led by strings to create a soft and tender tone. Lloyd Webber asks us to sympathize with the Phantom in this moment and again in one of the final scenes in the film when the Phantom sits with a music box softly playing a reprise of “Masquerade”.6Andrew Lloyd Webber. Phantom of the Opera. United States of America: Warner Brothers Pictures, 2004, 02:07:39. A tragic hero is defined as a character that “typically [has] heroic traits that earn them the sympathy of the audience, but also [has] flaws or [makes] mistakes that ultimately lead to their downfall.”7Chelsea Hogue. “Tragic Hero.” LitCharts LLC, May 5, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2020. https://www.litcharts.com/literary-devices-and-terms/tragic-hero. A tragic hero is exactly what Lloyd Webber has created out of the Phantom and highlights it in the music he wrote for the character.

The Angelic Christine Daae

In comparison to the Phantom, there is never really any doubt about how we are supposed to understand Christine Daae’s character. From her very first performance in the opera house, Daae is an innocent girl who is destined to be troubled by love but ultimately have her happy ending. In the opening scenes of The Phantom of the Opera, Carlotta is the opera house’s leading soprano. However, she is whiney and high maintenance and under new management she is not pleased enough to go on with her performance. That is the moment Daae steps in. Daae has an impromptu audition for the next leading role by singing the song Carlotta had just finished rehearsing, “Think of Me”.

People within the opera house are seen putting earplugs in and grimacing while Carlotta’s harsh voice sings the song. But moments later, Daae’s singing is juxtaposed to Carlotta to hammer in her soft, angelic character. This use of juxtaposition forces the audiences to find Christine more pleasing to listen to, an obviously favorable trait to have in this story. The juxtaposition is an example of the use of the virgin-whore dichotomy in literary and theater pieces. To further this image of Daae as the virgin, the scene then transitions into Daae’s opening night performance of “Think of Me” where she is adorned in a beautiful white dress.8Andrew Lloyd Webber. Phantom of the Opera. United States of America: Warner Brothers Pictures, 2004, 00:17:00. White serves as a literary symbol of innocence and virginity. Daae’s innocence is unmistakable even from the beginning.

The leading instrument behind Daae’s music throughout the film also drive home her innocence in a holistic way. Early on, Madame Giry makes an off-handed comment about Daae’s late father being a renowned violinist.10Andrew Lloyd Webber. Phantom of the Opera. United States of America: Warner Brothers Pictures, 2004, 00:11:11. This context might seem unimportant, until one pays close attention to the music that guides Daae’s character throughout the film and realizes the violin is at the heart of her theme. String instruments, most notably throughout the film, create an air of grace and beauty around Daae. Her innocence is driven home with the violin at the heart of her characterization through music. The violin is a symbol of what made her an orphan when she was young. She is a young girl who overcame a great tragedy. Lloyd Webber is just asking the audience to be in awe with this angelic girl who has incredible, intoxicating talent.

Conclusion

What makes Lloyd Webber’s musical and film even more effective exists at the intersection of the Phantom and Daae’s relationship. The musical complexity of the Phantom’s character does not just fool the audience. Daae herself is caught up in the complexity of the Phantom’s characterization. She hears the whispers of the opera house that his disfigurement has led him to be a violent mad man. But then she remembers her father telling her an angel of music would be there to guide her and she believes the Phantom could be that angel of music. She herself sees both sides of the Phantom that make him the tragic hero in this story. Her innocence plays into this as well because the audience forgives her for her naivety of staying friends, even accepting the potential of being more than friends, with a man murdering innocent people because others do not follow his commands. It seems as if the audience is guided down the same journey as Daae every step of the way with the music subconsciously leading each step the audience and the characters make. The achievement of redefining traditional operatic roles and instrumentation while at the same time utilizing the classic, traditions of a musical score is impressive. The complexity of it all helps explain how The Phantom of the Opera is the longest running show on Broadway. The musical transcends time because it invites the audience in with intent to keep them on their toes until the very end. You can’t get enough.

References

| ↑1 | The Phantom of the Opera. IMDb.com. Scion Films Phantom Production Partnership, 2004, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0293508/mediaviewer/rm3963456512/. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Andrew Lloyd Webber. Phantom of the Opera. United States of America: Warner Brothers Pictures, 2004. |

| ↑3 | The Phantom of the Opera. IMDb.com. Scion Films Phantom Production Partnership, 2004. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0293508/mediaviewer/rm2878245888/. |

| ↑4 | Blake Howe. “Disability Studies for Musicians: An Introduction.” Music and Disability at the SMT and AMS. Music and Disability Studies at the American Musicological Society and the Society for Music Theory, November 20, 2013. https://musicdisabilitystudies.wordpress.com/2013/11/20/disability-studies-for-musicians-an-introduction/. |

| ↑5 | Andrew Lloyd Webber. Phantom of the Opera. United States of America: Warner Brothers Pictures, 2004, 00:31:00. |

| ↑6 | Andrew Lloyd Webber. Phantom of the Opera. United States of America: Warner Brothers Pictures, 2004, 02:07:39. |

| ↑7 | Chelsea Hogue. “Tragic Hero.” LitCharts LLC, May 5, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2020. https://www.litcharts.com/literary-devices-and-terms/tragic-hero. |

| ↑8 | Andrew Lloyd Webber. Phantom of the Opera. United States of America: Warner Brothers Pictures, 2004, 00:17:00. |

| ↑9 | The Phantom of the Opera. IMDb.com. Scion Films Phantom Production Partnership, 2004. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0293508/mediaviewer/rm697207808/. |

| ↑10 | Andrew Lloyd Webber. Phantom of the Opera. United States of America: Warner Brothers Pictures, 2004, 00:11:11. |