What is debasement?

Simply defined, debasement means to reduce the precious metal content of the coin. Debasement can take form by either altering the weight, fineness, or face value of a coin.

- Weight refers to the physical weight and mass of the coin.

- Fineness refers to the quality of the metal in the coin.

- Face value refers to the value that is actually printed on the coin.

Who debased their currency?

Currency debasement occurred on both a governmental level and an individual level. The methods in which both levels occurred are drastically different with the debasement on the individual level often being found as illegal.

Why would a government debase their currency?

There are two primary reasons why a government would debase their currency: to raise money and to increase the quantity of money in circulation throughout the economy.

The first reason a government would debase their currency would be to provide an alternative to the traditional methods of raising money such as increasing/collecting taxes. It was common for an individual to give their bullion to the mint and receive coin of equal value in return. However, the government could raise money by keeping a portion of the bullion, and issuing less weight in the form of coins in order to boost the money in their coffers. Through altering the weight of the coin, they are essentially debasing their currency as they are decreasing the intrinsic value of the coin (the value attributed to the melted down value of the coin).

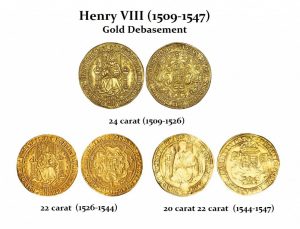

- Henry VIII and his son radically debased gold and silver coins from 1542 to 1551, which later became known as the Great Debasement. This tactic allowed them to skim off progressively greater amounts of metal at the mint, coin it, and then spend the new coin as if it remained unchanged in quality or quantity. As a result, the mint was forced to repeatedly raise their price to attract more metal, which diluted silver from the sterling standard of 96.5% fineness down to a 25% fineness in the coins.[1] A portrait of King Henry the VIII is displayed to the right.

- Noted in the image below, is an example of the gold debasement that occurred under Henry VIII’s rule with images of coins being debased from 24 carats to 20 carats in a relatively short period of time.

Image Source: https://www.armstrongeconomics.com/research/monetary-history-of-the-world/by-country/england/henry-viii-1509-1547/

The second reason a government would debase their currency would be to increase the quantity of money in circulation throughout the economy. A government would want to increase the quantity of money in circulation when there is a shortage of precious metals and not enough to make the amount of coin they wanted. A shortage of coin would decelerate the velocity of money throughout the economy, be harmful to trade amongst merchants, and often harmed the poorer individuals in the economy in a number of different ways. Through altering the weight of the coins issued or through altering the fineness of the metals’ quality, the government could thereby issue more money into the economy as they decreased the intrinsic value of the coin.

- During the 17th century Elizabethan era, demand for coin during the Queen’s reign was pushed up by population growth, increased urbanization, rising prices, and more extensive monetization. According to most scholars of the period, the expanding currency had not kept pace with demand.[2] The economy started facing a negative backlash from the lack of coin in circulation and the only real solution at the time was for the government to debase their currency through the mint. A portrait of Queen Elizabeth I is displayed to the right.

Why would an individual debase currency?

An individual typically debased their currency in an attempt to make a profit. Debasement by the individual generally took the form of either the clipping or sweating of coins.

- Clipping refers to shaving metal from around the edge of a coin.

- Sweating refers to shaking the coins in a bag and collecting the dust that has worn off.

When the individual debased the currency, they were physically removing precious metal from the coin and would pass the coin on at face value. The precious metal that was physically removed could be melted down which left the debaser with a profit. The image shown below represents a great example of a clipped coin from the time period.

Image Source: https://mythofsyph.wordpress.com/2013/08/06/god-sovereignty-and-silver-clipped-coins-and-bitcoins/

A less common method of debasement by the individual was known as punching or plugging. If a coin was large enough, a hole could be punched out of the face in the center of the coin and hammered in until the hole closed. Additionally, other individuals would saw a coin in half and remove part of the inside of the coin. After filling the coin back up with a cheaper metal, the debaser would weld the two pieces of the coin back together and profit on the precious metal they removed.[3]

What was the punishment for an individual debasing their currency?

The debasement of coins on an individual level had substantially eroded the amount of precious metal in the English coin to the point where it was no longer able to circulate at par.[4] The debasement of coins on an individual level had been considered a capital crime for centuries, but the threat of death had not sufficiently deterred people from attempting to earn a profit off of this illegal activity. Additionally, it was extremely difficult to determine who had actually applied their shears, files, or hammers to the coins. Furthermore, many debasers who were actually caught were often pardoned or acquitted because juries found the death penalty to be too harsh of a punishment for a crime that was considered by many to have no specific victim.[5]

What measures were taken to prevent an individual from being able to debase their currency?

One measure was the mechanization of the minting process in 1663. Rolling mills were created to flatten the bullion and presses were created to cut out blanks and stamp them. This technology significantly improved the consistency across the new coins being minted. Additionally, the new machines left a grooved imprint around the circumference of each coin, which made clipped and shaved coins much easier to detect.[6]

What effects did debasing currency have on trade and the economy?

Newer and full-weighted coins were often the first to be exported during international trade. Many European countries experienced different levels of debasement throughout the time period, and some refused to accept significantly debased or low value coins being passed off at face value. Coins used in international trade were typically passed on by their weight. As a result, debased coins had to be passed on for a reduced amount in international trade; compared to their full face value when used domestically. As seen in England, this caused the best coins to leave the country while they retained the older, hammered coins which continued to erode.[7]

What notable figures argued in favor of or against currency debasement?

Despite the severe debasement that occurred in the time period leading up to the 1690s, the English coin had continued to circulate around par. However, as debasement practices accelerated and the scrutiny surrounding the issue intensified, confidence in the gold and silver coins quickly evaporated.[8] A great debate was sparked between two notable figures during the time period known as William Lowndes and John Locke who discussed many issues that were related to the best practices for coin and how to approach the issue.

One of the notable figures who spoke on the topic of coin and many of the issues surrounding it was Treasury Secretary William Lowndes. Lowndes believed in debasement, but only at the governmental level in which it should be controlled. He proposed that England should re-coin the nation’s currency, using the most current technology to prevent debasement, but with 20 percent less silver in each coin.[9] Lowndes was particularly confident that their new technology would be enough to help eliminate the majority of their debasement issues, but still believed that a controlled level of governmental debasement was needed for the economy. Specifically, Lowndes was proposing a debasement in line with the market price of silver. Lowndes argued that everyone would receive the same amount of money as before the re-coinage with a controlled debasement. Lowndes further argued that in theory, the ability of a coin to pay off a debt is dependent upon its face value, and not the metal content of the coin itself.

The second notable figure was John Locke, who was against all forms of debasement and believed that the silver standard could not be altered. As noted by Wennerlind, Locke suggests that money circulates on the basis of its intrinsic value and that people part with their commodities because they know they are being offered its equivalent weight in silver. Additionally, Locke believed that people accept silver on the basis of the belief that it can be exchanged for other goods in the future.[10] Locke believed that any form of debasement would be doing landlords and creditors a disservice. If landlords and creditors lose faith in the future value of coins, they will be less likely to participate in the economy and make loans to those who need them. As a result Locke believed that loans and the ability to take out credit would begin to diminish, and the economy would be negatively impacted.

Lowndes and Locke both share the viewpoint that individuals should not debase their currency. However, they disagree fundamentally on where a coin derives its value from. Furthermore, their disagreements are grounded on whether the government should be able to debase their currency in a controlled manner in order to support trade and the overall flow of money throughout the economy. Locke prevailed in the end and won the debate over Lowndes. The English coin was eventually re-coined and was issued without any debasement in the silver of the coins.

Written by Luke Robertson

References:

[1] Desan, Christine. Making Money: Coin, Currency, and the Coming of Capitalism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015. 232

[2] Ibid., 236.

[3] Sheerwood, Sidney. The History and Theory of Money … Philadelphia: S.n., 1893.

[4] Wennerlind, Carl. Casualties of Credit: The English Financial Revolution, 1620-1720. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011. 123

[5] Ibid., 126.

[6] Desan, Christine. Making Money: Coin, Currency, and the Coming of Capitalism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015. 237

[7] Ibid., 237.

[8] Wennerlind, Carl. Casualties of Credit: The English Financial Revolution, 1620-1720. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011. 128

[9] Ibid., 129.

[10] Ibid., 130.