The latest from UR professors Scott T. Allison and George R. Goethals, authors of Heroes: What They Do and Why We Need Them.

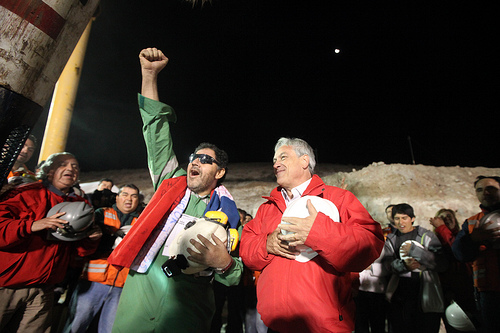

The world seems hungry for heroes. That appetite was on display when the Chilean miners were set free after 70 days being trapped under a half mile of rock and rubble. At different times, all 33 miners, or their leader, Luis Urzua, or the rescuers, or the Chilean president, or the whole country seemed to be heroes. An undoubtedly great event had taken place, and observers craved to identify the heroes of the historic rescue. The individual who seemed to be the most obvious was Urzua. As the foreman of the crew locked underground, he seemed to have performed magnificently as the group's leader.

The world seems hungry for heroes. That appetite was on display when the Chilean miners were set free after 70 days being trapped under a half mile of rock and rubble. At different times, all 33 miners, or their leader, Luis Urzua, or the rescuers, or the Chilean president, or the whole country seemed to be heroes. An undoubtedly great event had taken place, and observers craved to identify the heroes of the historic rescue. The individual who seemed to be the most obvious was Urzua. As the foreman of the crew locked underground, he seemed to have performed magnificently as the group's leader.

Most impressive seemed to be Urzua's ability to get the miners through the first seventeen days, before a probe finally reached them. During that time the miners had no way to knowing whether they would ever be rescued. Urzua persuaded the men to stringently ration their food and water. They had enough for 48 hours, but Urzua anticipated that the rescue might take much longer than that. At first the men limited themselves to a few bites of tuna fish, some fruit, and a half glass of milk each day. But as the days stretched on, the men were issued rations only every 48 hours. Finally, the outside world made contact with the men, and hopes rose that they might in good time be rescued. Initial estimates were four months.  But the efficiency of the rescue operation was truly magnificent. In that context, the behavior of the miners as a whole and of Urzua as leader seemed flawless.

But the efficiency of the rescue operation was truly magnificent. In that context, the behavior of the miners as a whole and of Urzua as leader seemed flawless.

But then other information trickled in that suggested that their story was not so simple or so neat. As the men faced starvation, and possible cannibalism, discord and despair descended on the group. While Urzua tried to maintain cohesiveness, subgroups began to form, each with its own agenda. Some planned their own escape. Petty squabbles and even fist fights broke out. Some men refused to get out of bed, seemingly overcome by hopelessness and depression. As food became more limited, and the men had to drink filthy, polluted water, their bodies began to consume themselves. And their minds just waited for death.

Once the miners were contacted, and hopes rose for a rescue, a very pretty picture was painted of Urzua's leadership and the miners' response to it. The narrative included the fact that Urzua was the last person to be rescued. It all seemed very tidy. However, while none of the disturbing information above was included in most accounts, there were signs that all was not well. For example, only 28 of the 33 miners appeared in early videos sent up to the surface. Where were the others, and why were they not seen?

Once the rescue was achieved, it seems that what happened below ground will stay there. The men involved have no reason to air their fears, failures and conflicts in the world spotlight. Even more perhaps than the miners, the public has little use for dissonant elements that might diminish the heroic story. Human beings need a steady diet of heroism. The thirst for it seems unquenchable. And few want heroic waters to be polluted by the complexities of human interaction under intense stress.