Heresy

The English word heresy comes from the Old French eresie, heresie (12th century), which was itself derived from the Latin haeresis, word referring to a philosophical or religious school of thought or sect, and the Greek word hairesis, meaning “the holding of a particular set of philosophical opinions.” The emergence of Christianity meant that the term adopted religious significance, particularly the categorization of doctrine and practices that fell outside the Church’s beliefs. As early as the writing of his epistles, St. Paul warned the early Church about false teachings that deviated from the Christ-centered gospel he preached. By the time of the Middle Ages, however, heresy was defined as religious beliefs or practices that contradicted the doctrine and authority of the orthodox Catholic church. In 1302, Pope Boniface VIII declared in his famous papal bull Unam Sanctam, “urged by faith, we are obliged to believe and to hold that there is One Holy Catholic and truly Apostolic Church. And this we firmly believe and simply confess: outside of Her, there is neither salvation, nor the remission of sins.” Thus, during the medieval era, the commonly held belief was that the Church dictated the means to spiritual salvation and anybody or anything that questioned the Church’s doctrine of salvation was heretical.

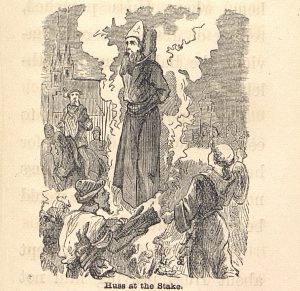

Heresy could spring up regardless of social rank or background. One early attacker of the Church and a precursor of the Protestant Reformation was John Wycliffe (1320-1384). A renowned scholar at the University of Oxford, Wycliffe used his influence to question the doctrine of substantiation, papal authority, and clergy’s excessive wealth, as well as to translate the Scriptures into the English language. Wycliffe’s outspoken teachings led to five papal bulls and threats of incarceration. Jan Hus (1369-1415), a Bohemian scholar who embraced Wycliffe’s writings, was not as fortunate. He was declared a heretic at the Council of Constance and condemned to be burned at the stake in 1415.

Other heretics were completely disconnected from scholarly circles. In

southern Germany, the peasant shepherd boy Hans Behem instigated a mass pilgrimage to the village of Niklashausen after claiming that the Virgin Mary had appeared and spoken to him in a vision. There he preached against the material and spiritual abuses of the clergy to thousands of peasants, culminating with the radical call to kill all priests. Although calls for reform of the clergy and Church were not new in fifteenth- cen

tury Germany, Hans’ readiness to base his reform on his heavenly visions rather than on the Church’s established authority marked him out as a dangerous heretic. Perhaps one of the most well-known heretics of medieval Europe was Martin Luther (1483-1546). Originally an Augustinian monk, Martin Luther is now commonly considered the founder of the Protestant Reformation. Although he sought reform within the Church rather than the creation of a separate church, Luther’s stance that only God – and not the Pope or Church- could grant a person salvation by “faith alone” placed him in opposition to the religious authorities. Although Luther and his writings were declared heretical at the Diet of Worms and he was excommunicated by the Pope, he escaped imprisonment and execution.

Works Cited:

http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/86195?redirectedFrom=heresy#eid

https://www.britannica.com/topic/heresy

http://www.catholicplanet.com/TSM/Unam-Sanctam-English.htm

https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Wycliffe

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jan-Hus

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Martin-Luther

Lindberg, Carter. The European Reformations Sourcebook. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2000.