Augsburg Confession (1530)

Keith Oddo

Augsburg Confession (1530)

Martin Luther saw himself as a man of truth; he wanted to eradicate the corruption that permeated the institution of Roman Catholicism. He advocated that Christians should be free to interpret the Bible and to make their own decisions, instead of blindly obeying the Roman Catholic establishment. The idea that the Bible, and not the Catholic Church of Rome, should guide Christians, completely contradicted the sixteenth- century mandates of Roman Catholicism. Fundamentally, Luther succeeded because his ideas appealed to people of all classes, ranging from peasants to princes. Early in 1521, Luther was excommunicated from the church and lost his citizenship in the Holy Roman Empire. He was threatened by Church elite, including Cardinal Cajetan, who said, “If you want to be a member of the church and have a pope who is gracious, then recant everything. In that case, nothing shall happen to you…” (Lindberg 31). Within a decade after Luther’s excommunication, however, it was evident that efforts to silence protestant reformers were futile. In 1530, forced to unite Christian sectors against the invading Turks, Roman Emperor Charles V, invited Lutherans to explain their religious convictions. In response, Lutherans presented the primary tenants of their faith, in what became known as the “Augsburg Confession.”

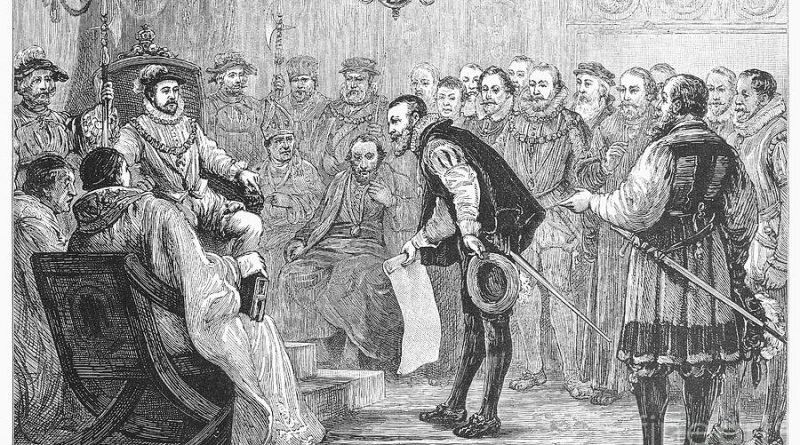

At the same time that Lutheranism was undermining the institution of Roman Catholicism, Emperor Charles V, desperately needed military forces to combat the invading Turks. “The emperor was worried because the Turkish army (made up of Muslims) was attacking Austria and threatening to overrun Europe (Thompson). Emperor Charles V was convinced that it would take a united Christian force to defeat the Turks. In 1530, Emperor Charles V, commanded the Lutherans to attend a council in the southern German town of Augsburg, in order to enforce a resolution and stop the Protestants from declaring their own faith that was separate from the Holy Roman Empire. The ultimate goal in calling this meeting was to achieve religious uniformity. Notably, Martin Luther was not allowed to attend because he was still considered an outlaw of the Church. As a result, Philip Melanchthon, a reformer, theologian, educator, and dear friend to Martin Luther, defended Luther’s views. Although Cardinal Legate Campeggio tried to repress the reformers, “Charles V, promised a fair hearing, and the Lutherans followed Bruck’s advice and formulated a written confession of their faith” (Lindberg). Based on past writings from Luther and his followers, Philip Melanchthon and one other official wrote the Augsburg Confession, which consisted of 28 articles. The first twenty-one articles outlined what specifically the reformers believed were the most essential teachings of Lutheranism, based on the Bible. The last seven articles emphasized many of the wrongs and abuses of the Roman Catholic Church and provided arguments for needed change if the two parties were ever going to reunite together again. In all, seven Lutheran princes decided that the Augsburg Confession accurately represented their views of religious faith and practice.

The Confession was written in both German and Latin, and the German translation was read to the council at Augsburg on June 25, 1530. The Catholics, in response, criticized the articles and wrote a long letter to the Lutherans, which was later countered again by Melanchthon. Although there were initial steps taken towards a peaceful resolution, conflict between the Protestant and Catholic leaders in the Holy Roman Empire continued until the Peace of Augsburg was signed in 1555. However, nearly 500 years later, the Augsburg Confession is still noted for its significance as the primary confession of faith of the Lutheran Church.

Works Cited

Lindberg, Carter. The European Reformations Sourcebook. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2014.

Thompson, Glen L. “The Unaltered Augsburg Confession.” V-36. http://www.stpls.com/uploads/4/4/8/0/44802893/augsburg-confession.pdf.