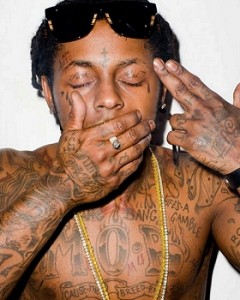

Note: This cites Lil Wayne lyrics, so it’s a tad raunchy.

A couple of weeks ago, Young Money boss Lil Wayne made news when, at the last second, he pulled Nicki Minaj from Hot 97’s Summer Jam 2012. It turns out one of the station’s personalities, Peter Rosenberg, had disparaging comments about Minaj’s song “Starship,” which he (rightly) described as “bullshit.” Lil Wayne didn’t appreciate the dis, so he pulled Minaj from the concert to show how much he respects women.

That’s right, the rapper who routinely drops some of the most repulsive, misogynistic lyrics in the business has apparently had some kind of epiphany. “Nicki Minaj is a female,” he said, quickly scoring a point with his correct gender identification. “I don’t know what anyone else believe, but I believe females deserve the ultimate respect at all times, no matter what, where, when, or how.” When I read this, there was something about his repetition of “female” here and elsewhere in the interview that felt a little off, but I was probably reading into things too closely, I decided. Good for Wayne. Good for rap.

This morning, I decided to give Tech N9Ne’s new-ish album (from 2011) a listen–it got pretty good reviews when it came out, and even though I’m not a huge fan of his twisted tales, I admire his dedication to the industry. He’s been around for decades. In any case, I saw that Wayne was featured in a very respectful-sounding song called “F**k Food,” and I was excited to hear evidence of his transformation.

Having heard Wayne’s part in the song, I can now confirm that his respect for women does indeed run deep. Right out of the gate, his opening line–“put that p**sy on my lip and dip”–puts his listeners on notice that this ain’t the same old Wayne, and a few lines later when he says, “I beat that p**sy like brass knuckles,” I almost start to feel guilty for doubting his sincerity. I wouldn’t be surprised to read that brass knuckles line on a Hallmark wedding anniversary card. And the lucky lady on whom he’s lavishing all of this respect (surprisingly not given a name or a voice) must feel kind of embarrassed that this famous rapper puts her on such a pedestal. Somehow it gets even better; by the end of Wayne’s verse, she’s just about achieved God-like status. In rapid fire rhymes, he elevates her thus: “I’m makin’ her talk, I’m makin’ her beg / I’m makin’ her crawl, I’m makin’ her run.”

Forget the sublime poetry for a moment–this recognition that women should be treated with dignity and, yes, respect is most welcome. I’ve been worried that rappers like Wayne were beyond help, but here, I’ll say it, I was wrong. As if compelled to make his point one last time, Wayne’s last line–“I got that f**k food, baby, come taste it”–removes any lingering suspicions. Haters step off–Wayne means what he says. This is the “ultimate respect at all times” that he was talking about.