http://www.mediafire.com/view/?2dvtec1ccu283u1

Here’s the Interdisciplinary Studies thesis by Michael Rogers, Class of 2011 that I mentioned in class! So relevant to what we’ve been talking about.

http://www.mediafire.com/view/?2dvtec1ccu283u1

Here’s the Interdisciplinary Studies thesis by Michael Rogers, Class of 2011 that I mentioned in class! So relevant to what we’ve been talking about.

Pratt describes 1960s Richmond as having Black schools that were overcrowded and white schools that were not filled to capacity— all of which were all overseen by a Richmond Public School System (RPS) that used discriminatory practices to keep black children in inadequate, segregated schools (Pratt, 36). Meanwhile, RPS used the Pupil Placement Board (PPB) as a crutch to deflect blame for their delay in fulfilling the Brown ruling.

John and Joe both highlight the impact that residential segregation had on school segregation; Pratt weaves this connection through all three chapters. One such example of school segregation based on residential segregation is the feeder system that existed in Richmond. Typically, white middle schools “fed” white high schools and black middle schools “fed” black high schools. As John points out in his timeline, in March 1963, this feeder system was abolished. As a result, a new “freedom of choice” plan was established that technically allowed any student to transfer to any school she wanted if she could support the reasoning. However, Pratt argues that despite the new façade of choice, black students still had to filter through the racist PPB. In addition, the problem of segregated teachers along race lines was not addressed. Even after Brown was 11 years old, RPS was still fighting to maintain school segregation by enacting school reform policies that used residential discrimination.

Caitlin

Just found this article and wanted to pass it along. It has some more background about the “Stand Your Ground” law in the Trayvon Martin case:

http://mediamatters.org/blog/201203200009

From our last class discussion about the “staging” of Rosa Parks’ bus boycott, to recalling our realization that MLK was not a one man band who single-handedly crafted the civil rights movement, it shocks me to think about how much our text books glazed over America’s historical truth. When I think of the history that most of us learned in elementary school, the only thing that comes to mind is: “Columbus sailed the ocean blue in 1492”.

In part II of Chapter 7, we learn just how dark the shadow of World War II is. In incidents like explosion that killed 202 navy seamen in July 1944 at the Port Chicago, San Francisco, the United States government treated black soldiers with no human dignity (273). Branding black soldiers as rapists when there was no substantial evidence (272). Removing all dignity. Violent, widespread lynchings. Intense voter intimidation… Before this class, I didn’t have an accurate perception how inhumanely the government, and many American citizens, treated black Americans throughout history. As the NAACP worked to end discrimination and secure full citizenship for black Americans, widespread violence is still going on. Why didn’t we learn about this extreme violence in high school!

Another thing that came up in our last class discussion was how hard it must have been to be an organization like the NAACP to be fighting against a system that is completely set against you. It’s so eye-opening to hear these stories and to begin to feel the experience of black Americans in the 20th century. To gain a better picture of living every day in fear for your life and knowing that if any white person accused you of something you could probably not defend your innocence. In Chapter 7 and 8, we see Marshall working tirelessly to defend and advocate for black Americans through the NAACP. In just the year 1944, he traveled more than 42,000 miles working for social justice (286). His steadfast and determined character in such a time of danger speaks to incredible leadership.

As the wartime oppression turned into a demand for “justice now,” this line stuck out for me: “if black men and women rejected the idea of being a ruled group, they ‘must be willing to make every sacrifice necessary to retain the right to vote’” (285). We’ve never lived through a time when our population has had to fight for the right to vote, so it’s easy for the full importance of suffrage to escape us. Truly comparing our own lives to the lives of the black Americans of the civil war era, is eye opening to say the least.

How many of you have taken your full citizenship for granted? Did you learn about the true civil rights history in high school (if you did, was it just a really good teacher?) Although Prof. Fergeson was joking, it really does seem like we need college history to correct, or give a more complete story, to what we’ve learned in the past. Drawing from chapters 7 and 8, what are some things that you learned that you didn’t know before, and you think you should have known? Any comments on the seeming inadequacy of high school history classes?

– Caitlin

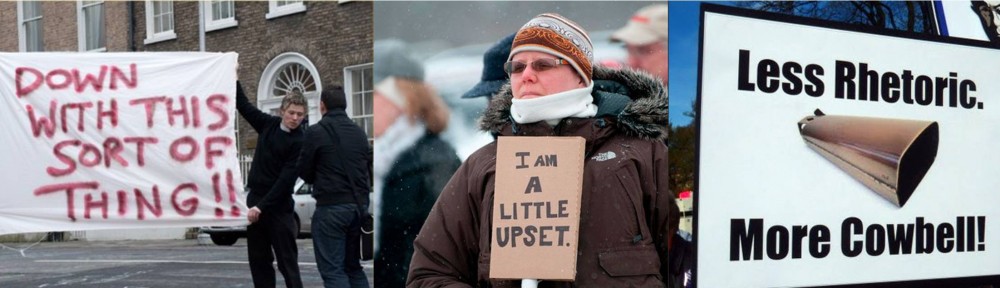

Chapter 8, “When Everyone Protests,” is way to start thinking about both sides of a protest and movement-countermovement dynamics. I thought Lucie did an excellent job of giving an overview of Myer’s points, so I won’t re-state those. Among other specifics in the chapter, such as getting the attention of people with political power, I was most interested in Meyer’s take on the importance of professional organizers in movements. Especially as we being to think about countermovements and the necessity of responding to the “other side,” professional organizers might be vital to the success and impact of a protest. As Lucie mentioned in her post, activists must put energy into their own movement, but also engage with the countermovements and publicize rebuttals.

Meyer first introduces professional organizers in Chapter 3, Becoming an Activist. There, he gives a good background about who becomes an activist, and the different types of activists that exist. Specifically, Meyer notes that “movement professionals” are people who support themselves through organizing and political efforts. These people do not just view the movement as a hobby, but as a lifestyle; there is always something to do that could be advancing the cause within the movement. Meyer says that movement professionals “develop a stronger vested interest in the survival and well-being of their organizations than will the rank and file activist” (55).

As we think more about countermovements, it’s good to acknowledge all the work that goes into managing the movement’s own message as well as incorporating responses to media coverage of the countermovement. Considering the bigger picture, Meyer points out that movements have become more complicated in general: “Whereas protest was the province of those without other means to make political claims effectively, it is now an add-on or component of the political strategy of an increasingly broad range of groups” (159). Today, instead of all attention going into the protest, there are not a lot more considerations, such as current policy, lobbying, outreach campaigns to other organizations, e-mail and telephone communication, applying for police permits and posting bail.

Here are some questions I’ve had. What do you think?:

-Caitlin Manak

Today, I found an article in the Huffington Post that serves as a great example of the power of media in social movements. Last week, One Million Moms (an affiliate of the American Family Association) attacked JCPenny for hiring Ellen DeGeneres based on her sexuality. In the “Gay Voices” section of the online newspaper, activist and blogger Scott Wooledge, gives reasons why the smear campaign will actually be ammunition for the LGBT community:

“The LGBT community owes a great big thanks to the “One Million Moms” (actually, closer to 40,000) for launching the best LGBT-friendly public relations blitz the community has seen in ages, and battering Christian conservative’s image in a way the LGBT community could never hope to do.”

The fact that One Million Moms is using moral judgement as grounds for employment discrimination has even gotten Bill O’Rielly talking. (In the article, there is a clip of O’Rielly passionately defending non-descrimination in the workplace.) In addition, GLAAD, the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation, has started a campaign in response, called “Stand Up for Ellen”.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/scott-wooledge/million-moms-ellen-jcpenny_b_1272420.html

Thoughts?