History

By Chase Williams

Key Definitions:

- Central Bank: or monetary authority is a singular and often nationalized institution that has control over the production and distribution of money and credit.

- National Bank:

- A bank chartered by the U.S. government and formerly authorized to issue notes that served as money.

- A bank owned and administered by the government, as in some European countries.

The existence of national and central banks has always between a contentious and controversial issue from the days of William III, to President Andrew Jackson, and into the present with modern cyberlibertarianism.

Original Formation:

In 1609, in the bustling port city of Amsterdam foreign merchants conducting business were plagued by the instability in value of different coins and the circulation of different currencies. As a result, Dutch officials set out to remedy the situation and encourage trade. Thus, the first national bank, the Bank of Amsterdam (or Wisselbank) was founded to protect foreign merchants. The bank protected foreign creditors by, “by settling debts through the bank and offering depositors its own coins that were not debased” (Desan). The term debasement should be understood in the sense that when a coin is “debased” the amount of gold or silver in it has been depleted making it worth less. The bank did not make loans to the public and importantly acted as a service to merchants who were trading in different currencies. According to Douglas, “Its main contribution to banking innovation was a system of transfers by checks and direct debits similar to how it works now” (Douglas).

Rise of England:

The “role of the Wisselbank diminished after 1650; this was because London took over Amsterdam’s position in international trade, and because the ban on private banks was lifted, after which private banks regained their share of payment handling” (Desan). In the late 1680s and early 1690s London was the trading capital of Europe, a position which it took over from Amsterdam. Despite being the center of the European economic world England faced a number of significant challenges, including the fact that it had recently come out of the Glorious Revolution and was on the precipice of war with France. As a result the of these costly expenditures the country’s gold and silver reserves were greatly depleted. Parliament looking to fund the government’s expenses was forced to address the complex question of where to get the money to meet its obligations (Douglas).

Calls for a Bank of England

There were no easy answers. The most obvious solution might to borrow, but it wasn’t feasible as “if the money be advanced by way of loan by private persons, it mist be drawn out of trade, and so trade ruined” (Desan). Furthermore, Charles II’s recent default on the Treasury Orders greatly damaged investors’ faith in the government. Collecting taxes would have taken to long and been far to laborious. As the monetary situation worsened the young administration of William III faced monumental challenges not only in addressing the economic situation, but the impending threat from the rising power of France under Louis XIV (Desan).

As the amount money in circulation became more and more scare the proposals for paper cash grew louder. Willam Patterson and Charles Montague two of the most powerful men in the Whig party proposed a radically new system that called for “a bank, or public fund” which would in effect establish production of a cash medium that was convienient as tender and for income (taxes). It also and most importantly, provided funding to government to satisfy their debt obligations. The system was set up in a similar way to a modern subscription model where anyone could buy banks note with the expectation that they could return them at given time for the amount plus interest. The issue of debt obligation is particularly important because without them England would be severely limited in its ability to get enough financing to fight another war.

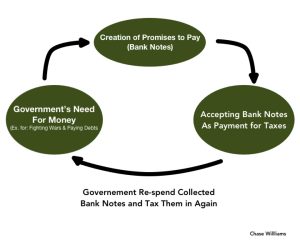

Below I have included a graphic that shows how the proposed Bank of England would address the government’s money shortage.

For Whigs the proposal “represented a new means of finance. Although many were vague on the specifics, banks promised money and a means to pump it into circulation” (Desan). This optimistic perspective was not shared by the opposing party, the Tories, who believed that the Bank would lower land values and increase interests rates. Instead, the Tories favored alternatives such as a land bank (Desan).

Nonetheless, the Whigs led the charge for paper cash and this new system of government funding as the Crown needed cash immediately. Its solution, The Bank of England, was enacted by Parliament and granted a Royal Charter in 1694 by King William III. According to the Bank of England’s website, King William III issued the Original Royal Charter of 1694 under the auspices of promoting, “the public Good and Benefit of our People” (Bank of England). Interestingly, while it could be inferred that an improved monetary situation could be in the interest of the public good, primary sources indicate that the primary issue was resolving the government’s debt. Regardless, as part of the benefit to English society the Bank was able to issue money, in the form of banknotes, which were more similar to modern stock grants than the dollar bills you and I use today now. While the original national banks were quite simple compared to their modern predecessors, that evolution didn’t happen overnight. Desan describes this gradual change in the usage of the notes as, “Initially, the Bank probably used the notes as those bankers had, in transactions with private clients. The notes were first identified as “for the use of the House,” apparently a reference to the Bank’s commercial lending business, although the Bank would soon turn to them in its dealings with the government as well.” The reference to government usage was largely to that they were used to collect taxes, which is huge, because for the first time people could not pay their taxes through alternate means such as gold and silver. Moreover, it made it easier because it did not require taxpayers to have to deal with the issues such as debased coins and the Crown could have a more standardized collection process. Most critically, it allowed the government to easily re-spend the taxes it collected. Finally, as private banks over time were unable to to compete with notes issue by the Bank, they slowly left national banks (Bank of England in this case) to dominate the role of producing paper currency.

The Early United States

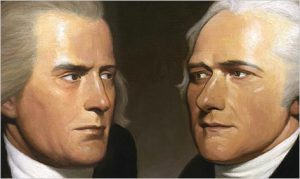

Following its successful quest for independence from Britain the young United States under the Articles of Confederation faced stiff challenges in regaining economic stability. In 1789, the Articles were abandoned in favor of the Constitution, which created a federalized system and sparked a great debate between a number of the Founding Fathers about the constitutionality of a national bank. The debate was primarily between Jefferson and Hamilton who were drastically different views on the power granted by the Constitution. Hamilton proposed that a national bank be chartered to allow the United States to establish a line of credit, and expand its commerce / national industry. This plan took a heavily federalized approach taking the Revolutionary War debt away from the states, as well promoting commercial activity and industrial economic development (Hamilton). Hamilton justified his plan by arguing the ‘Necessary & Proper Clause’ permitted such governmental actions. Jefferson on the other hand was an advocate for a different type of American economy, one that favored agriculture over industry. Despite Jefferson’s difference of opinion about which direction the American economy should head, he strongly believed unlike Hamilton that because the power to create a national bank was not enumerated in the Constitution it was unconstitutional. In addition to Jefferson and Hamilton, James Madison, an architect of the Constitution stood closely to Jefferson on the issue. While Madison noted the merits of the Bank he concluded, “that the power exercised in the bill [Proposal for Bank of the United States] was condemned by the silence of the Constitution” (Madison). Thus, Madison was in agreement with Jefferson because they both believed in and acknowledged the potential benefits of the Bank, but refused to support its enactment because the Constitution did not explicitly grant the power to do so. In the end, Hamilton won out and his plan to federalize the debt, establish a line of credit, and produce a national currency prevailed.

The Age of Jackson

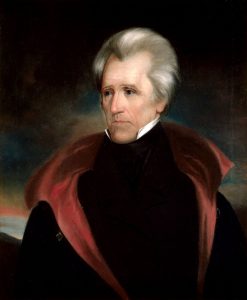

Many Americans they have heard the legendary folk tales of President Andrew Jackson’s quest to ‘kill’ the Bank of the United States before it ‘killed him’. While much of these stories have become full of fictional enhancements, there is some underlying truth. Jackson’s fight to destroy the bank is rooted in his populist platform of appealing to average white men (whom were new voters because restrictions on the requirement to own property to vote were recently relaxed) (Greenstein). The Bank of United States was a private institution with a federal charter that allowed it to among other promoted the corrupt “monied interests” as Jackson saw it. Importantly, ‘monied interest’ was not Jackson’s political base, they were the ones whom were most staunchly opposed to Jackson and took active steps to originally to block him from the White House ie. “the Corrupt Bargain” (Greenstein). Furthermore, the Bank of United States provided many of Jackson’s opponents with money that could to influence others against him, whether that be in the press or other candidates. In 1832, the Bank was up for recharter and Jackson vetoed the Bank believing it was unconstitutional because it was beyond the scope of the enumerated powers (Jackson).

Into the Present

These stories along with the complex nature of national and central banks, such as the Federal Reserve, have sewn a lasting mistrust of these institutions into the American & global consciousness. While Jackson attempted to “kill” the bank because he thought it only served elites, the bank and its modern predecessor the Federal Reserve play important, and often unseen, roles in our daily life from setting the money supply, to the interest rates that affect our home mortgages, and issuing the printing of currency.

Bibliography

Desan, Christine. Making Money: Coin, Currency, and the Coming of Capitalism

“History.” Bank of England. December 5, 2017. Accessed April 25, 2018. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/about/history.

Douglas, Peter. “THE AMSTERDAMSCHE WISSELBANK.” New Netherlands Institute. Accessed April 5, 2018. https://www.newnetherlandinstitute.org/files/5313/5396/7824/Amsterdamsche_Wisselbank.pdf

Greenstein, F.I. (2009) Inventing the Job of President: Leadership Style from George Washington to Andrew Jackson

Frame, Iain (2012) “Country rag merchants” and “octopus tentacles”: an analysis of law’s contribution to the creation of money in England and Wales, 1790-1844.

Alexander Hamilton, Report on the Subject of a National Bank (1790), 1-23

“James Madison’s Speech on the Bank Bill 2 February 1791” in Lance Banning, ed., Liberty and Order: The First American Party Struggle (Liberty Fund, 2004)

Alexander Hamilton, Opinion on the Constitutionality of a National Bank, 15 February 1791, in Liberty and Order

“Thomas Jefferson’s Opinion on the Constitutionality of a National Bank 15 February 1791” in Liberty and Order

“James Madison to Thomas Jefferson on Speculative Excess, Summer 1791” in Liberty and Order

Sklansky, Sovereign of the Market, Chapter 3, “William Leggett and the Melodrama of the Market (pp. 93-130)

President Andrew Jackson’s Veto Message Regarding the Bank of the United States, July 10, 1832