In this chapter, Meyer details the pattern of political institutionalization of social movements that has come to characterize some movements in the United States. He uses the antinuclear movement of the 1970s, the longer term US populism and agricultural movements, and US labor movements as the exemplars for explaining the patterns and mechanisms of institutionalization.

Meyer provides an operational definition of institutionalization as “…the creation of a stable set of relationships and procedures such that the politics of an issue becomes routine, that is, repeatable for all concerned with minimal uncertainty or risk… The boundaries of possible reforms are reasonably clear to all concerned and are limited” (126). He then outlines several mechanisms of institutionalization:

- “…policy makers can incorporate movement concerns by offering consultation, formal or informal, with representatives of a movement” (126)

- “…elected officials can offer social movement activists a platform or a venue for making their claims” (127)

- “…government can set up more permanent venues for consultation, formally adopting the concerns, and even sometimes the personnel, of a challenging movement” (127)

- “government can institute procedures that give an actor or claimant formal inclusion in a deliberative process” (128)

- “…policy reform can afford activist concerns a place in the process and resources attendant to that place” (128)

- “institutionalization includes norms and values, not only in government, but also in the broader culture” (128) *noted as critical by the author*

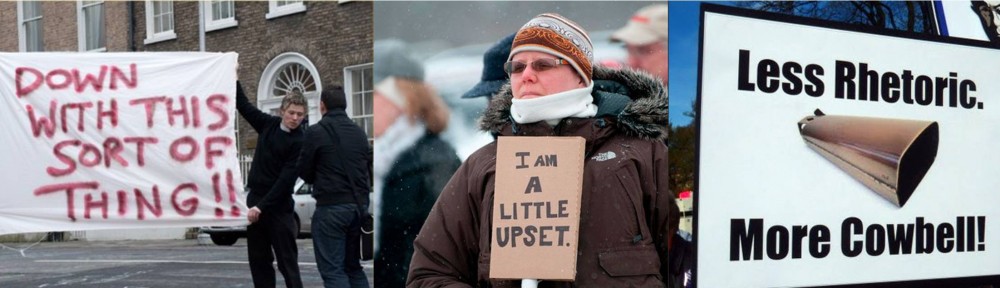

What struck me the most about this chapter was the indirect, implicit discussion of legitimacy. To me it seems that at the foundation of this process of institutionalization is a search for the right place, a sense of permanence, the right people, and recognition for the need and the possibility for reform. What the process of institutionalization does for a social movement is accommodating the needs of the cause while providing them with a form of legitimacy. Following this train of thought, if this particular cause is being welcomed into the political system then it must have a legitimate claim to be taken seriously. In the title of this blog post, I ask in jest “Social Movements, Too Legit to Quit?”. But, I think this question has resonance with what Meyer discusses in this chapter because there seems to be a catch-22 with institutionalization. The process does not just fuel the activistism and/or activist participation. The social movement becomes institutionalized and gains legitimacy but gaining legitimacy may prompt activists to question what else they can do for their cause. Can institutionalization make a movement “too legit” and make the activists quit?

After reading this chapter, I’m left considering the following questions which I now pose to you:

- Is the process of institutionalization as described by Meyers just another way of phrasing the process of negotiation? Or is it a grander process of gaining legitimacy? Or is it simply selling out?

- Do you think that institutionalization is necessary or even inevitable?

Can you imagine OWS engaging in institutionalization? Or would that be completely antithetical to the cause?

Brittany Mangold