In a word: Versatile.

In a sentence: Civil Disobedience is a tool of social movements used by an individual or group to protest a law or common practice, and can change over the course of the movement from a spark of ignition to a unifying action.

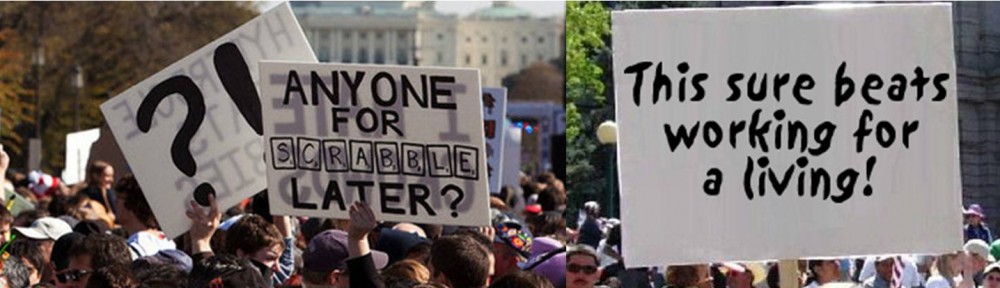

In a picture:

The OWS Student Strike in NYC (Rights owned by me, so no copyright issues)

Types of Civil Disobedience:

Individualistic-Often dramatic, and in accordance with an individual’s own ‘higher law,’ individualistic Civil Disobedience is an action of one or a few who find a present practice or law against their beliefs—religious, secular, or otherwise—and take action. Meyer’s example is of a woman who bars all other women entrance to an abortion clinic.

Collective-In acting not against a law or for a ‘higher law,’ collective Civil Disobedience relies on disagreement with a common practice that goes against the ‘collective value’ of a large group. Meyer’s example is of a fictional play in which women withhold sex and chores until war ends. Though not breaking laws, they are breaking customs. See ‘Famous Users’ for more.

Primary uses of Civil Disobedience:

Bring attention and inspire action-At the beginning of a movement, Civil Disobedience can bring media attention to an issue and inspire involvement by previously dormant citizens. Case in point: Rosa Parks refusing to give up her seat on the bus. (spark)

Unify a campaign- In the course of a movement, Civil Disobedience can serve as a common thread linking protestors, leaders, and events. Case in point: MLK and Ghandi used non-violent civil disobedience to gain the moral high ground and control the direction and methodology of protests.

Famous users/uses of Civil Disobedience:

Women and Prohibition-Though Meyer’s does not mention this in his fictional account of women withholding sex, many women in America actually did withhold sex, cease household labor, and acted generally against the grain in a response to the obscene drinking of the early twentieth century. The result: prohibition. This illustrates perfectly collective Civil Disobedience.

MLK and the Civil Rights Movement-Referred to constantly my Meyer’s and used by analysts around the world, the Civil Rights Movement illustrates both individualistic Civil Disobedience and Collective Civil Disobedience in the ways written about through the piece.

The Take-away

The key to understanding the different uses of Civil Disobedience lies not in the result or the people involved, but the origin of the action. In assessing whether or not a movement is effectively using Civil Disobedience at the right moment in the course of a movement, one must look at why it occurred. Did a single person or small group act in favor of a ‘higher law’ or a ‘collective value’?

With that in mind, how is Civil Disobedience used by the Occupy movement? Which kind? At what time? How about the Tea Party?