Suetonius, Divus Augustus 74-77

translation and commentary by Emily Dixon (’23)

Introduction

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, commonly referred to as Suetonius, was a Roman author and biographer who lived from 69 CE to sometime after 122 CE. His most famous surviving work The Life of the Caesars (De vita Caesarum) contains twelve biographies, covering the lives of Julius Caesar and the first eleven Roman emperors, from Augustus to Domitian. Published in 121 CE during the reign of the emperor Hadrian, it is one of the most important primary sources for the study of the end of the Roman Republic and the early Roman Empire. However, the reliability of the text has long been a source of debate, considering the text’s often sensational and gossip-like tone, as well as the validity of Suetonius’s sources and any personal biases he may have held (Rolfe 1914).

The second book of Suetonius’s De vita Caesarum is a biography of Rome’s first emperor, Augustus. Born in 63 BCE as Gaius Octavius, Augustus was the adopted son and heir to Julius Caesar. After the assassination of Caesar in 44 BCE, Augustus (then Octavian) formed a political alliance with Marcus Lepidus and Mark Antony known as the Second Triumvirate. Together they defeated Caesar’s assassins at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BCE. After the exile of Lepidus in 36 BCE and the defeat of Mark Antony at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, Octavian was left with sole power. He took on the title of Augustus in 27 BCE and restored the illusion of the Roman Republic while still maintaining autocratic rule. During his reign he greatly expanded the borders of the empire by annexing new provinces such as Egypt, and he promoted an era of peace and stability known as the Pax Augusta, or “Augustan Peace.” He made great strides in developing infrastructure in the city of Rome and elsewhere in the Roman empire and was a great patron of art and architecture. He had one biological daughter, Julia, with his second wife Scribonia. He divorced Scribonia in 38 BCE in favor of Livia Drusilla, and he and Livia remained married until his death in 14 CE. The sections presented here describe Augustus’s peculiar habits surrounding eating, drinking, and dining. For more on the life of Augustus, see this page from World History Encyclopedia.

Translation

[74] He was constantly throwing dinner parties, always formal ones, and not without great care to the status of his guests. Valerius Messala says that he never invited freedmen to dinner except Menas, but only after he was admitted among the freeborn after he betrayed the fleet of Sextus Pompey. Augustus himself writes that he once invited a man, in whose villa he was staying, who had once been his own bodyguard. Sometimes when he went to dinner parties he both arrived late and left early, and the guests began to dine before Augustus was reclining and they would remain seated when he left. At his dinners he would serve three courses, or sometimes six when he was feeling most lavish, not excessive with his spending, but with the highest camaraderie. He used to draw into the discussion those who were being silent or telling stories with a low voice, or he would introduce artists, actors, or even common players from the circus, and more frequently, story-tellers.

[75] He used to celebrate festivals and ceremonial days most lavishly, sometimes in a great joking manner. On Saturnalia, and whenever else he felt like it, he used to distribute gifts, sometimes clothes and gold and silver, sometimes coins of all kinds, such as those of old kings and foreigners; occasionally he distributed nothing except hair coverings and sponges and pokers and fire-tongs and other things with obscure and misleading names. At dinner parties he used to sell lots of the most unequal types and paintings with their backs turned, so by risky chance he would either disappoint or fulfill the hope of the buyers, and the bidding would happen by each couch, so they would share in either the loss or the profit.

[76] Concerning food — for I should not omit even these things — he ate little and had a generally plain diet. He most especially liked second rate bread and small little fishes and moist hand-pressed cheese and twice-bearing green figs. He would even eat before dinner, whenever and wherever his stomach desired. These are the words from his own letters: “In the carriage we ate bread and little dates.” And again: “While I returned home from the Regia in a litter, I ate an ounce of bread and a few berries from a cluster of hard-skinned grapes.” And yet again: “Not even a Jew, my Tiberius, fasts so diligently on the Sabbath as I have today, when eventually in the bath after the first hour of the night I ate two mouthfuls before I began to be anointed.” Because of this irregularity he sometimes used to dine alone either before a dinner party or after it was dismissed, and he touched nothing while the dinner party was ongoing.

[77] He was also by nature extremely sparing in his use of wine. He wasn’t used to drinking more than three times before dinner in the camps near Mutina, Cornelius Nepos says. Even afterwards when he indulged himself the most, he did not exceed a pint, and if he did, he used to throw it up. He loved Rhaetian wine most of all, but he didn’t drink it casually throughout the day. Instead of a drink he used to take bread soaked in cold water or a piece of cucumber or a stalk of lettuce or an apple with juice like a tart wine, either fresh or dried.

Commentary

[74]

“he was constantly throwing dinner parties, always formal ones” (convivabatur… recta): The cena recta (commonly translated as formal dinner) was a specific kind of Roman dinner party in which wealthy patrons would invite their clients to dinner as a reward for their service, particularly in the Republican era (509-27 BCE). The practice fell out of use in the early imperial period in place of food-filled gift baskets (sportula) or simply gifts of money (centum quadrantes) but was revived under the reign of the emperor Domitian (81-96 CE) (Jones 1935, 357).

For more on the Roman patron-client system, see this YouTube video which demonstrates a day in the life of a Roman client.

Valerius Messala: Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus (64 BC – CE 8) was a Roman general, author, and patron of literature and art. He sided with Octavian (Augustus) and fought against Sextus Pompey in Illyricum and against Mark Antony in the Battle of Actium. The source Suetonius refers to here is almost certainly Messala’s memoirs, published in the late 20s, which are now lost (Wardle 2014, 461).

Menas: a Greek freedman, also known by the name Menodorus, who was granted admission into the equestrian rank (ingenuitas) by Augustus himself after he betrayed the fleet of Sextus Pompey and restored Sardinia to Augustus’s rule in 38 BCE (Badian et al. 1996).

“he himself writes” (ipse scribit): Presumably Suetonius pulled this anecdote from Augustus’s memoirs, which no longer survive (Wardle 2014, 461).

“he would serve three courses” (cenam ternis ferculis … praebebat): The Roman dinner (cena) typically consisted of three courses: appetizers or “tastings” (gustatio), the main course or “first table” (prima mensa), and dessert or “second table” (secunda mensa) (Raff 2011). In the case of extravagant dinner parties, as Suetonius discusses here, each course could be doubled.

“he would introduce…”: Entertainment was a large part of Roman convivia. Banquets saw performers of all types: musicians (who played instruments such as the lyre, the water organ, and the aulos, a double flute), singers, actors, dancers, acrobats, pantomimes, and poetry readers (Raff 2011).

Roman Banquet by Joseph Coomans, 1876. Oil on canvas. (Wikimedia)

Although this 19th century conception of a Roman banquet contains some anachronisms, it effectively captures the conviviality of a feast.

“artists” (acroamata): A term transliterated from Greek that is used to describe various kinds of entertainers (lit. “things to listen to”). Mostly used to refer to readers, but can refer to musicians as well. (Wardle 2014, 463)

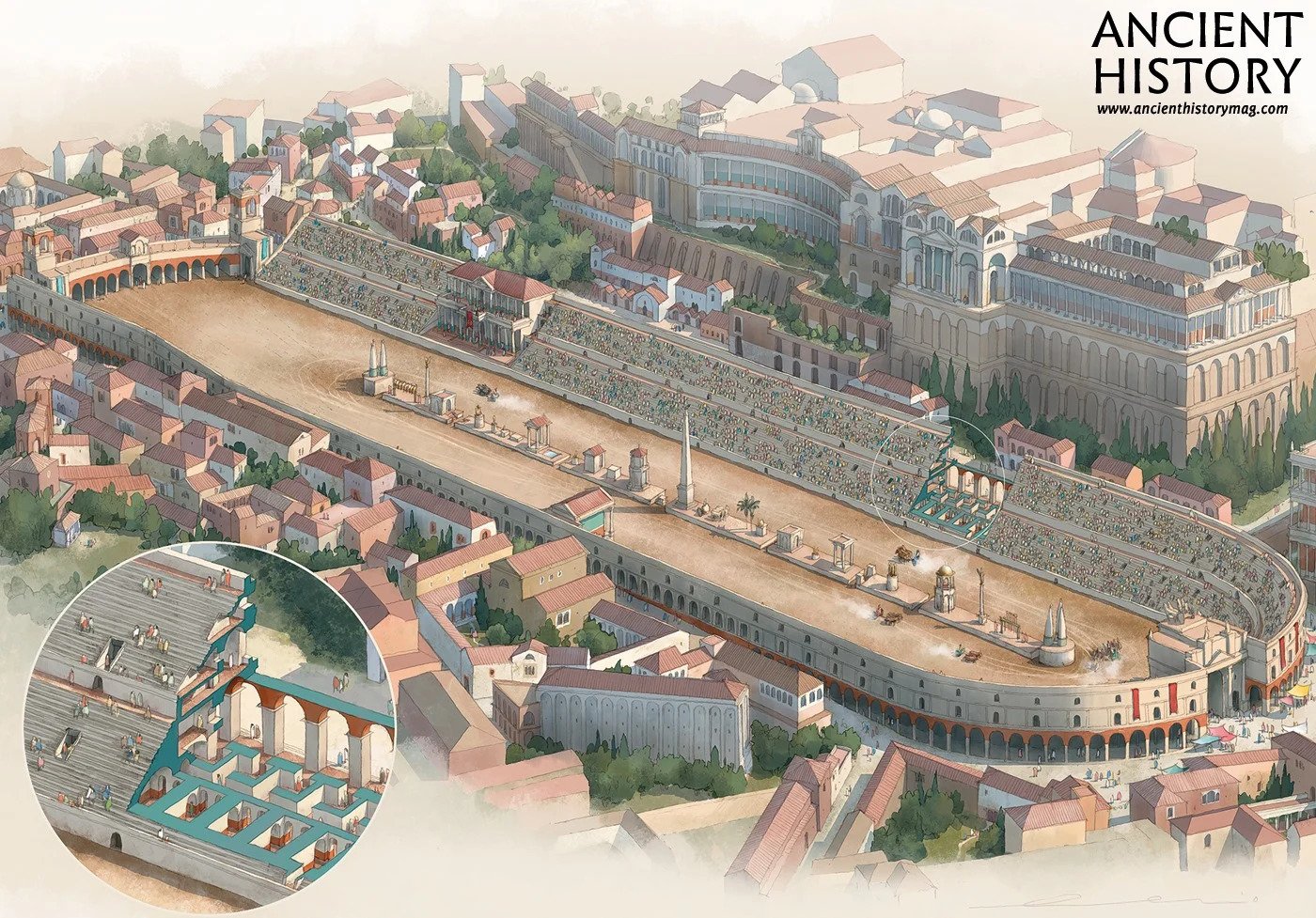

“common players from the circus” (triviales ex circo ludios): street performers who would stroll the street near the Circus Maximus (the largest chariot-racing stadium in Rome) and the imperial residence on the Palatine hill (Wardle 2014, 463).

Reconstruction of the Circus Maximus with the Palatine residence in the top right. The palace reconstruction seen here dates to the reign of Domitian (81-96 CE), who made extensive renovations to the palace.

(Image by Rocío Espin, Ancient History Magazine)

“storytellers” (aretalogos): Augustus seems to have been fond of story-tellers — Suetonius also reports that he would send for storytellers (fabulatores) when he could not sleep at night (Suet. Aug. 78).

[75]

Saturnalia: Saturnalia was the Roman festival to the god Saturn, which began on December 17th each year. The festival lasted for several days, growing in length as time progressed (Augustus himself extended the celebration period to three days). Saturnalia traditions included feasting, dice-playing, gift-giving (especially of clay and wax figurines known as sigillaria), and a role-reversal, in which masters served their slaves and people wore felt caps (pillea), which were symbols of freedom (Distelrath 2006).

“things with obscure and misleading names”: The names of some of the gifts listed here have double meanings — for example, the word for “pokers” (rutabula) can be used to mean an item to stir up a fire or a penis. Household items were commonly used as metaphors for genitalia (Wardle 2014, 464).

[76]

“second rate bread” (secundarium panem): Bread made with a mix of high quality wheat (siligo) and average quality wheat (pollen). This type of bread as well as the other foods listed (little fishes, hand-pressed cheese) emphasize Augustus’s humble qualities (Wardle 2014, 465-466).

“twice-bearing green figs” (ficos virides biferas): i.e., figs from trees that bear fruit twice a year. Augustus’s wife Livia supposedly poisoned him with figs (Cass. Dio 56.30.2), and the Romans subsequently cultivated a type of fig tree named the Liviana (Beard 2013, 131).

Regia: The Regia, literally meaning “royal palace,” was a structure in the Roman Forum likely used to host meetings for the chief priest (pontifex maximus) and his college of pontiffs and to store their records (Claridge 2010, 109). Augustus held the title of pontifex maximus beginning in 12 BCE until his death in 14 CE.

Marble sculpture depicting Augustus as pontifex maximus. Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome.

(Photo by Emily Dixon)

Tiberius: adopted son of Augustus, who married Tiberius’s mother Livia Drusilla in 38 BCE. Tiberius would become emperor upon Augustus’s death in 14 CE.

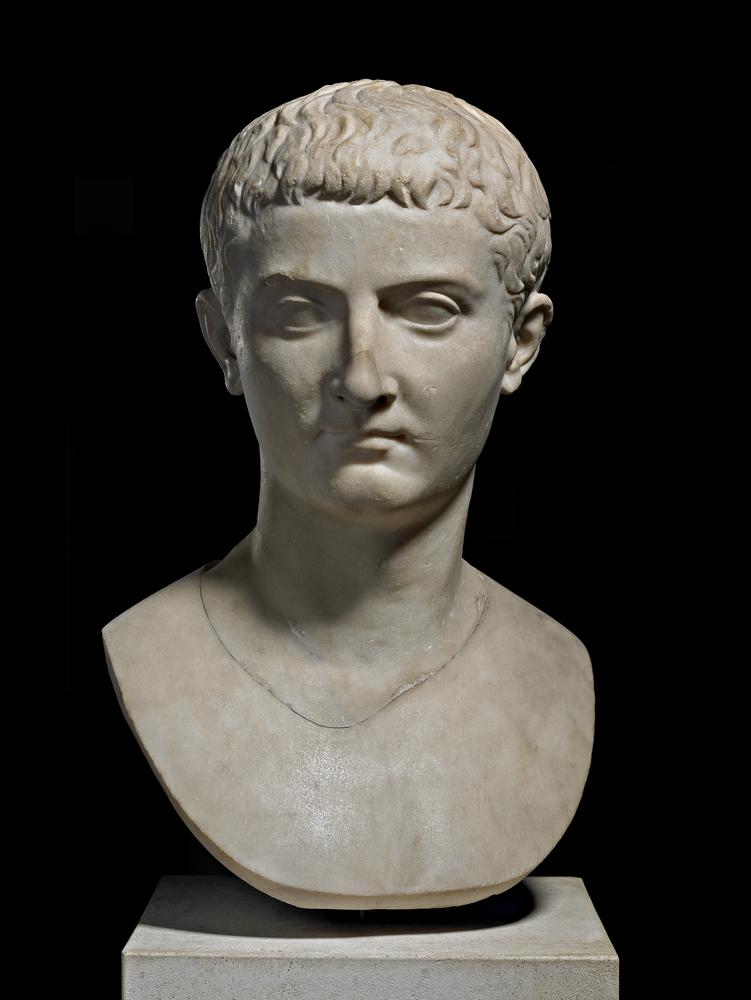

Marble bust of Tiberius; British Museum inv. 1812,0615.2

“Not even a Jew…”: Romans often had misconceptions about Jewish practices. Here Augustus holds the common misconception that Jews fasted on the Sabbath, a view shared by the authors Horace, Petronius, and Martial (Rankin and Wescott 1918, 345; Wardle 2014, 466).

[77]

Mutina: a town in the Roman province of Cisalpine Gaul near modern Modena in northern Italy. Augustus defeated Mark Antony in battle at Mutina in 43 BCE (Potter and Salmon 1996).

Cornelius Nepos: the earliest surviving biographer in Latin who lived from 110-24 BCE. His most complete surviving work is On Famous Men (De viris illustribus), detailing the lives of famous kings, generals, poets, and historians, both Roman and non-Roman (Rolfe et al. 1996).

Rhaetian wine: Rhaetia, a Roman province known for its wines, encompassed parts of modern Italy, Switzerland, Germany, and Austria. The Roman poet Vergil wrote in his Georgics of Raetian wine: “… and you, Rhaetic — how can I do you justice?” (et quo te carmine dicam, Rhaetica?, Verg. G. 2.83).

Map showing the location of Rhaetia within the Roman Empire (125 CE). Wikimedia

lettuce: Lettuce seems to have been a favorite of Augustus. Pliny the Elder also recalls a story in which Augustus’s physician Antonius Musa cured him of an illness by prescribing him a diet of lettuce (Plin. HN 19.128). The news of this story increased the popularity of lettuce and led the people to erect a statue to Musa near the statue of Aesculapius (the god of medicine) in Rome (Suet. Aug. 59).

Sources

Badian, Ernst, Theodore J. Cadoux, and Geoffrey W. Richardson. 1996. “Menodorus.” In Oxford Classical Dictionary, edited by John Hornblower and Antony Spawforth. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Beard, Mary. 2013. Confronting the Classics: Traditions, Adventures, and Innovations. New York, NY: Liveright Publishing Corporation.

Claridge, Amanda. 2010. Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Distelrath, Götz. 2006. “Saturnalia.” In Brill’s New Pauly, Antiquity volumes, edited by Hubert Cancik and Helmuth Schneider. Leiden: Brill Publishers. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e1102380

James, Malichi. 2017. “A Day in the Life of a Roman Client.” University of Kent. YouTube video, accessed May 4, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RJSZKNa_bgQ

Jones, Francis L. 1935. “Martial, the Client.” The Classical Journal 30, no. 6: 355–61. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3290674.

Potter, T. W. and Edward T. Salmon. 1996. “Mutina.” In Oxford Classical Dictionary, edited by John Hornblower and Antony Spawforth. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Mark, Joshua J. 2018. “Augustus.” World History Encyclopedia. Accessed May 4, 2022. https://www.worldhistory.org/augustus/

Raff, Katharine. 2011. “The Roman Banquet.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York, NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/banq/hd_banq.htm

Rankin, Edwin M. and John H. Wescott. 1918. Gai Suetoni Tranquili: De Vita Caesarum Libri I-II. Norwood, MA: Norwood Press.

Rolfe, J.C. 1914. Suetonius: Lives of the Caesars, Volume I. Loeb Classical Library 31. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rolfe, J.C., Anthony Spawforth, and Gavin B. Townend. 1996. “Cornelius Nepos.” In Oxford Classical Dictionary, edited by John Hornblower and Antony Spawforth. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Wardle, D. 2014. Suetonius: Life of Augustus. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.