Pliny the Younger, Epistles 5.6

translation and commentary by Weilan Moyer (’25)

Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus, known as Pliny the Younger, was a prominent Roman lawyer, author, and administrator who lived from 62 CE to 112 CE. His legacy comes from his “Epistulae,” a collection of private letters that offer a snapshot of Roman aristocratic life, politics, and culture during the late first and early second centuries (Sherwin-White 1969). Pliny’s career flourished under the emperors Trajan and Hadrian, which he served in various roles, including as governor of Bithynia-Pontus. Pliny the Younger sought fame and distinction, extensively writing to cement his name in history (McEwen 1995).

A highlight of his letters is Epistula 5.6, addressed to Domitius Apollinaris. This letter offers an intimate glimpse into Pliny’s life through a detailed description of his villa in Tifernum Tiberinum. Sharing the layout and aesthetics of his villa, Pliny not only reveals his own preferences and the leisure lifestyle of the Roman elite but reflects the broader Roman values and societal importance of landownership and private escapes. This letter notes the architectural preferences and domestic habits, highlighting Roman values and elite lifestyle. This epistula, like others, showcases Pliny’s skill in rhetorical approaches such as ekphrasis, and his deep engagement with the moral and ethical concerns of his era (Chinn 2007). The “Epistulae” as a whole, encapsulating both personal reflections and public discourses, serve as a valuable historical document that offers profound insights into Roman politics, social norms, and cultural paradigms.

Translation

Gaius Plinius (sends greetings) to his Domitius Apollinaris

[1] I loved your concern and care. When you heard that I was planning to visit my place in Tuscany this summer, you advised me not to go because you thought the area was unhealthy. [2] True, the coast of Tuscany is pretty harsh and can be unhealthy where it stretches along the shore; but the place I’m talking about is far from the sea. It actually lies beneath the Apennines, which are among the healthiest mountains around. [3] So to ease all your worries about me, let me tell you about the climate, the location, and how lovely the villa is. It’s something that will be pleasant for you to hear about and for me to talk about.

[ . . . In the next sections, Pliny details the idyllic landscape, where nature and the culture are intertwined. He describes the timeless beauty that surrounds his villa which is sustained by the gentle climate and ancient traditions, which come from the wise elders that remain there. Pliny describes the Tiber River, which serves as a lifeline as it shapes the agricultural activities of the region, illuminating the community and its connections to the environment.]

[13] You will take great pleasure, if you view the layout of this region from a mountain. For you will seem not to be looking at lands but rather at some form of exquisite beauty as if painted: such a variety, such a depiction; wherever the eyes fall, they will be refreshed.

[ . . . Then Pliny describes the villa and its combination of architectural sophistication with the beauty of the natural surroundings. At the base of the hill, the villa appears elevated and enjoys the gentle breezes from the Apennine mountains. Pliny includes the featured south-facing portico, gardens, and expansive meadows. He also includes “amenities” such as the hypocaust, a marble basing to enhance the shaded courtyard, and a sphaeristerium (ball-playing field). There are interior decorations like marble and nature-inspired paintings to unify the indoors with the outdoors. Overall, Pliny is exemplifying luxurious living, providing comfort and aesthetic pleasure.]

[29] Next to the summer quarters, there’s a high-placed cryptoporticus that seems not just to overlook the vineyards but to reach out and touch them. At the center, there is a dining room that catches the healthiest breezes from the Apennine valleys; through its wide windows at the back, you can see the vineyards, and the doors also frame the vineyard, but through the cryptoporticus, it’s like they’re being let in. [30] On one side of the dining room that doesn’t have windows, there’s a staircase that provides a more secluded route for bringing up dishes for the meal. At the end there’s a bedroom that enjoys just as delightful a view through the cryptoporticus itself as it does of the vineyards. Below lies another cryptoporticus, almost like an underground one; it stays cool with trapped cold air in the summer and doesn’t need or let in any breezes. [31] Past each cryptoporticus, at the end of the dining room, begins a portico which faces the morning sun in winter and the afternoon sun in the summer. This leads to two suites, one with four bedrooms and the other with three, designed so that as the sun moves, they either soak up the sun or enjoy the shade.

[ . . . Pliny goes on to describe the villa’s hippodrome, which surpasses the grandeur of all the other buildings. Centrally located, it is encircled by plane trees draped with ivy, creating a lush canopy. Boxwood and laurel add greenery and shade as well. The straight section of the hippodrome curves into a darker, shaded semicircle lined with cypress trees, contrasting with the bright inner areas that receive sunlight. Boxwood carved with various names and designs (topiary) run along the path. Shorter plane trees frame the central area, highlighting the intricate design of the hippodrome.]

[36] Beyond that, the acanthus is slippery and winding here and there, then you come across more figures and more names. At the head of the area, there’s a curved bench covered with white marble and shaded by a vine held up by four Carystian columns. From this bench, water seems to be squeezed out by the weight of those reclining, flowing through small spouts. It’s caught in a carved stone basin, contained by plain marble, and so cleverly managed that it fills up without overflowing. [37] Appetizers and the heavier dishes are placed along the edge, while lighter fare floats around in dishes shaped like little boats and birds. Opposite, a fountain shoots up water and then catches it; for the water thrown up falls back into itself, disappearing and being sucked back through joined slits.

Across from the semi-circular couch, the room opposite mirrors the decor of the semi-circular couch as much as it receives from it. [38] The room shines with marble, its doors open onto a greenery-filled area, and it looks out and down through upper and lower windows at other garden spaces. Soon, a small antechamber retreats back as if it were both the same room and a different one. There’s a bed here and windows on all sides, yet the light is dimmed by the pressing shade. [39] For a very cheerful vine climbs over the entire roof to the peak and up. It feels just like lying in a grove, except you don’t feel any rain, as you would in a grove

[ . . . Next Pliny describes the additional features of the hippodrome, highlighting the thoughtful design. A fountain springs up and is channeled throughout the area, with marble seats for visitors. Small fountains are next to these seats with streams that flow through, irrigating the green spaces described above (5.6.32-35). Pliny expresses his personal attachment to the design by highlighting his involvement or refining of the features.]

[42] In summary – why should I not open to you either my judgment or my error? – I consider the first duty of a writer to read his own title and repeatedly ask himself what he began to write, and know that if he dwells on his subject, it is not long, but very long if he brings in and attracts something else. [46] There, both in mind and body I am most robust. For I exercise my mind with studies and my body with hunting. My people also live nowhere healthier; so far, at least, I have not lost any of those whom I brought with me there – pardon the expression. May the Gods continue to preserve for me this joy and this glory of the place in the future! Farewell.

Commentary

[1] “…visit my place in Tuscany this summer (audisses me aestate Tuscos meos petiturum)” – Tuscany is the “west-central” region of Italy, which features rolling hills to “sharply peaked mountains” creating a barrier to the southern regions (Britannica 2024). Its northeast border is formed by the Apennine Mountains, which Pliny later describes.

Tuscany, Italy (Britannica 2024)

[3] “Let me tell you about the climate…” – Pliny addresses the concern of the “unhealthy coast.” Modern-day air-quality analysis shows the general region as having poorer air quality, relative to the rest of Italy. The location of Pliny’s villa is between mountain ranges, likely causing pollutants to become trapped; however, Pliny the Elder, Pliny’s uncle, goes into depth of the beauty and landscape of the region in his Naturalis Historia, here.

[4-12] – Pliny goes into great detail in describing the amenities of his villa. This reflects the importance of gardens and luxury in Roman culture. Gardens were an ideal and integrating urban amenities with countryside life, such as gardens and water features, were influenced by pastoral, rural life (Frazer 1992). “Villeggiatura” (staying in the countryside) in contrast with pastoral life is a blend of luxury and rural life. Pliny’s description of a serene, luxurious life at his villa highlights his social status as the upkeep required many servants (Frazer 1992). This leisure, otium, is prestigious as it allows Pliny to write and add “culture” (Leech 2003).

[13] “…not to be looking at lands but rather at some form of exquisite beauty…(terras…ad eximiam pulchritudinem pictam videberis cernere)” – Throughout the entire epistula Pliny uses ekphrasis to vividly explain the beauty of his villa; however, understanding the significance of views in Roman dining helps comprehend the importance of the “exquisite beauty”. Seating at the dining table was based on status. The seat a guest had signified how important they were and the lectus medius provided the best view for guests (Brown 2020).

Reclining in the Roman Triclinium (Brown 2020)

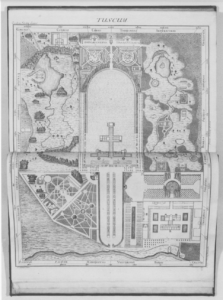

Drawing of Pliny’s Tuscan Villa by T. Wilson 1728 (McEwen 1995 Figure 1)

[14-28] – The depth Pliny goes into describing the architecture in conjunction with the natural surroundings can be explained as a form of ekphrasis, the literary device that entails vivid description of art (Chinn 2007). Chinn argues that the description along with Pliny’s actual experience signifies a sophisticated understanding of this device. One of the most famous examples of ekphrasis occurs in Homer’s Iliad, for the description of the Shield of Achilles.

Pliny also details the hypocaust, underfloor heating. Air was heated in a chamber then would flow through “pillars” under the flooring (Lamprecht 2006).

Example of a hypocaust system at Kourion, Cyprus (Britannica 2016)

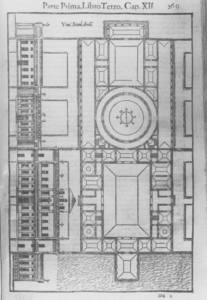

[29] “Next to the summer quarters…(A latere aestiva cryptoporticus in edito posita)” – A literal translation for “A latere” would be something like, “behind the villa”; however, as Sherwin-White indicates, “next to” makes more contextual sense (Sherwin-White 1966). A blueprint of Pliny’s Laurentine Villa reinforces this interpretation as the architectural layout would not permit anything to be placed behind that would face the vineyards as described.

Pliny’s Laurentine Villa by Vincenzo Scamozzi 1615 (McEwen 1995 Figure 2)

“there’s a high-placed cryptoporticus…” – A cryptoporticus was originally “a closed walkway lit by windows”; however, based on Pliny’s description and excavations from surrounding regions, in this instance it is a covered walkway that is part of the garden design (Höcker 2006). The Roman Villa Palazzi di Casignana, thoroughly excavated, provides a window into a visualization of what Pliny’s Tuscan villa really looked like, beyond speculation and recreations (Bruni 2009).

Outdoor Cryptoporticus, Roman Villa Palazzi di Casignana (Bruni 2009)

[30] “Below lies another cryptoporticus, almost like an underground one…(subterraneae similis)” – Comparable to the cryptoporticus of the Villa dei Misteri at Pompeii.

Underground Cryptoporticus, House of Cryptoporticus, excavated 1911-1929 (Pompeii 2022)

[31] “a portico which faces the morning sun in winter and the afternoon sun in the summer” – Pliny’s villa is situated in such a way that in his galleries, there is shade in the summer rather than sun in these specific rooms (Sherwin-White 1966).

Epistula 5.6.32-35 – The hippodrome was a central feature of Pliny’s Tuscan villa. A hippodrome is typically a circular race track used for chariot racing; however, Pliny is comparing the shape of his garden to this track (Bowie 2006). The landscaping of all the trees and boxwood that surrounds the hippodrome reflects the topiary art in this period (Lawson 1950). Additionally, Pliny is also using his intricate and ornate garden as a way to signify his status, imagination and sophistication (Jones 2014).

[36] “acanthus” – Acanthus mollis, unlike boxwood, was not meant to be shaped and designed but rather allowed to grow as it wishes lubricus et fluxuosus. This is underlying the Roman ideal of incorporating nature with architecture. The leaves of acanthus are the model of Corinthian columns (Zahrnt 2006).

Underground Cryptoporticus, House of Cryptoporticus, excavated 1911-1929 (Pompeii 2022)

“Carystian columns” – Pliny describes the columns holding the bench covering with a reference to Carystus. These columns are made of marble from Carystus, an ancient town in Greece (Kalcyk 2006).

House of Ephebe, excavated 1912; 1925 (Pompeii 2023)

“Stibadium” – A stibadium, also known as a sigma, was a common dining couch Romans used. It featured a semi-circular seating arrangement, accommodating diners to recline around a central table (Schmitt-Pantel 2006). It allowed for intimate conversation and social interaction.

“From this bench, water seems to be squeezed out by the weight of those reclining, flowing through small spouts (Ex stibadio aqua…effluit)”

Stibadium at Roman Villa at Fargola with little spouts that water would pour out of (Prey 2018)

[37] “While lighter fare floats around…(levior…innatans circumit)” – Marcus Terentius Varro is a likely influence of this rotating table. Varro’s, an ancient Roman scholar, work has been lost over time; however, his contribution to geography and Roman architecture lives on (Bernard 2014). Emperor Nero had a rotating dining room. While Pliny does not explicitly mention Varro, looking at Nero’s rotating dining room is a good starting point in visualizing how Pliny’s food was served. [Link to Seutonius (Celia’s Commentary)].

“Across from the semi-circular couch, the room opposite mirrors the decor of the semi-circular couch as much as it receives from it” (E regione stibadii…ab illo) – Pliny describes how his stibadium, with the Carystian columns and vines, is beautiful to look at and the gardens the seating faces is just as wonderful to look at. This reinforces the value of the lectus medius (Brown 2020).

Drawing of Pliny’s Stibadium (Prey 2018)

[42] “I consider the first duty of a writer…(primum ego officium scriptoris existimo)” – In understanding otium as Romans would, it must be contrasted with negotium (Leach 2003). This letter illustrates Pliny’s sophistication and status as he is spending his free time on noble pursuits: writing and philosophy, maintaining his mind and his body.

Sources

Architect of the Capitol. (n.d.). Corinthian columns. https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/art/corinthian-columns

Bernard, Seth G. 2014. “Varro and the Development of Roman Topography from Antiquity to the Quattrocento.” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 59/60: 161–79. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44981976.

Bowie, Ewen. 2006. “Hippodromos”. In Brill’s New Pauly Online, doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e514480

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. August 10, 2016. “hypocaust.” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/technology/hypocaust.

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. March 9, 2024. “Tuscany.” Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Tuscany.

Brown, Shelby. November 2, 2020. “Reclining and Dining (and Drinking) in Ancient Rome.” Getty Iris, https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/reclining-and-dining-and-drinking-in-ancient-rome/.

Bruni, Maria Gabriella. 2009. “The Monumental Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) during the Fourth Century AD”. Thesis diss., UC Berkeley.

Chinn, Christopher M. 2007. “Before Your Very Eyes: Pliny Epistulae 5.6 and the Ancient Theory of Ekphrasis.” Classical Philology 102, no. 3: 265–80. https://doi.org/10.1086/529472.

Frazer, Alfred. 1992. “The Roman Villa and the Pastoral Ideal.” Studies in the History of Art 36: 48–61. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42620375.

Höcker, Christoph (Kissing). 2006. “Crypta, Cryptoporticus”. In Brill’s New Pauly Online, doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e308210

Jones, F.M.A. 2014. “Roman Gardens, Imagination, and Cognitive Structure.” Mnemosyne 67, no. 5: 781–812. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24522234.

Kalcyk, Hansjörg (Petershausen), and Yves (Bochum) Lafond. 2006. “Carystus”. In Brill’s New Pauly Online, doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e609940

Lamprecht, Heinz-Otto (Cologne). 2006. “Heating”. In Brill’s New Pauly Online, doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e505680

Lawson, James. 1950. “The Roman Garden.” Greece & Rome 19, no. 57: 97–105. http://www.jstor.org/stable/642035.

Leach, Eleanor Winsor. 2003. “Otium As Luxuria: Economy of Status in the Younger Pliny’s Letters.” Arethusa 36, no. 2: 147–65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44578904.

McEwen, Indra Kagis. 1995. “Housing Fame: In the Tuscan Villa of Pliny the Younger.” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 27: 11–24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20166914.

Pompeii Sites. 2023. “House of the Ephebe.” https://pompeiisites.org/en/archaeological-site/house-of-the-ephebe/.

Pompeii Sites. 2022. “House of the Cryptoporticus.” https://pompeiisites.org/en/archaeological-site/house-of-the-cryptoporticus/

Prey, Pierre de la Ruffinière du. 2018. “Conviviality versus Seclusion in Pliny’s Tuscan and Laurentine Villas.” Chapter. In The Roman Villa in the Mediterranean Basin: Late Republic to Late Antiquity, edited by Annalisa Marzano and Guy P. R. Métraux, 467–75. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schmitt-Pantel, Pauline. 2006. “Sigma”. In Brill’s New Pauly Online, doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e1112420

Sherwin-White, A. N. 1969. “Pliny, the Man and His Letters.” Greece & Rome 16, no. 1: 76–90. http://www.jstor.org/stable/642902.

Sherwin-White, A. N. 1966. “The Letters of Pliny: A Historical and Social Commentary.” Oxford: Clarendon P.

Zahrnt, Michael (Kiel), and Christian (Hamburg) Hünemörder. 2006. “Acanthus”. In Brill’s New Pauly Online, doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e111580