Third Wave Feminism

Black and white photo of protesters holding signs at the New York City Women’s March in 2018. The signs in view are about intersectional feminism.1

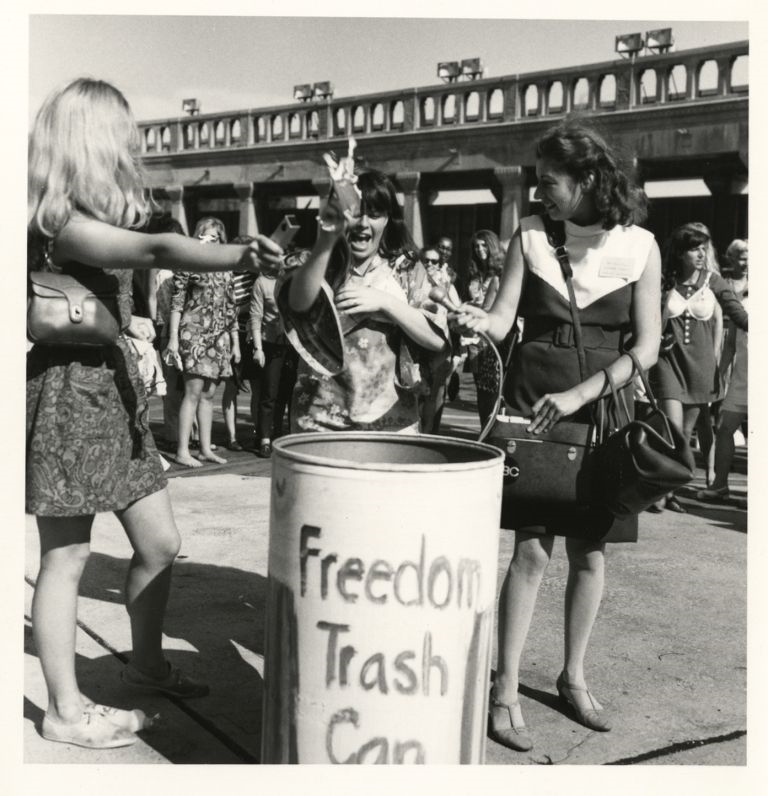

Protesters throwing bras into a garbage can at the Miss America Beauty Pageant in 1968. This protest is often referred to as the “bra burnings.” However, there was no fire at the instruction of the police officers on scene.2

History of Feminism

Historically, feminism has been divided into three distinct waves. The first wave refers to suffrage movement culminating in the 1910s. Second Wave feminism began in the 1960s, as the Women’s Liberation Movement, with aims of increasing economic equality, and especially, the right to control fertility for white married women.3 Third Wave feminism arose in the 1990s with a renewed emphasis on intersectionality within the understanding of womanhood and femininity. Intersectionality refers to “the interaction between gender, race, and other categories of difference in individual lives, social practices, institutional arrangements.”4 The third wave sought to reclaim feminism from the backlash of the 1980s for a new generation of women who saw it in a more inclusive manner than their predecessors.

Girl Power

Feminist discourse in Third Wave feminism surrounded “girl power” and who could use it. Riot Grrls, a female punk music movement, originated the term as a means of opposing mainstream media in a call for women to express themselves. This manifested itself in the DIY nature of punk because these women developed and created both their music and feminism independently of men.6 In the late 1990s, “girl power,” in the mainstream, became associated with the Spice Girls, a British pop music girl group. Their cooption of “girl power” invoked the experience of ordinary girls who then purchase Spice Girls merchandise. This was achieved through the marketing of the band as individuals within the larger group allowing fans to identify with different, individualized members.

Though some argue that the Spice Girls “domesticat[e] and subvert feminism, reducing it to a collection of empty slogans,”7 it is more accurate to understand the Spice Girls and their brand of “girl power” as a stepping stone to the more sophisticated, feminism preached by the Riot Grrls. To the Spice Girls, “girl power” is about empowerment that makes young girls feel good about their identity in an age appropriate manner, that is, focused on youth and friendship.

A pink 3D heart with “girl power” stitched on to it. It is reminiscent of a patch that someone might iron on to a jean jacket.5

- Julie Bindel and Danny Sjursen, “Why We Need Black Feminism More Than Ever Under Trump,” 2018.

- Yeoman Lowbrow, “Dispatches From The 70s: Women’s Lib Akin To An Irritating Rash,” 2015.

- Sue Bruley and Laurel Forster, “Historicising the Women’s Liberation Movement,” 2016, 699.

- Kathy Davis. “Intersectionality as Buzzword: A Sociology of Science Perspective on What Makes a Feminist Theory Successful,” 2008, 68.

- “The Ultimate Girl Power Playlist.” The Odyssey Online, Odyssey, 28 Aug. 2017, www.theodysseyonline.com/the-ultimate-girl-power-playlist

- Rebecca C. Hains, “The Significance of Chronology in Commodity Feminism: Audience Interpretations of Girl Power Music”, 2014, 33.

- Catherine Driscoll, “Girl Culture, Revenge and Global Capitalism: Cybergirls, Riot Grrls, Spice Girls,” 1999, 187.