There is much to be learned about leadership by studying the past. In particular, we learn about good leadership by studying what great leaders did and how they accomplished it. At the Jepson School, we have organized our curriculum with a nod to the past: as we put it, we study “leadership as it was, as it is, and as it should be.”

Professor McDowell’s powerful keynote speech at the Jepson School’s senior awards ceremony, Finale, on May 12, supported this approach. Dr. McDowell remarked that upon graduation, Jepson alumni will most importantly “learn to give proper vent to your ambition to succeed in actually making a difference. For ambition properly understood — that is to say ambition properly tempered and tamed — is not a vice but a virtue.”

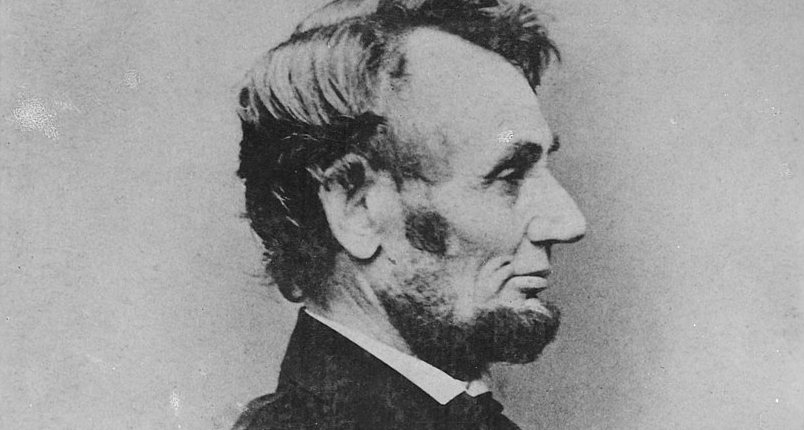

More than this, Dr. McDowell illustrated his point using the example of Abraham Lincoln, whom he called a “self-consciously ambitious” leader: “In one of his earliest political utterances, he confessed that his ambition was that of being ‘esteemed of my fellow men, by rendering myself worthy of their esteem.’” From my own areas of research, it is remarkable that Adam Smith distinguished between being esteemed (he used the word “praised”) and worthy of esteem (“praiseworthy”) in his 1759 Theories of Moral Sentiments.

In Dr. McDowell’s view, Lincoln’s “true legacy is a legacy of leadership. In particular, a legacy of moral leadership.” We learn (at least) four lasting insights from this moral leadership:

First, we must to a great extent work with human nature as it is, rather than expecting people to change radically: “human action can be modified to some extent but human nature cannot be changed.”

Second, as Dr. McDowell notes, Lincoln recognized that human nature is motivated by a combination of self-interest and moral sense: “Let us be brought to believe something is morally right, and, at the same time favorable, or, at least, not against our interest…and we shall find a way to do it, however great the task may be.”

Next, leaders, especially political leaders, must contend with what Lincoln referred to as “public sentiment,” which, Lincoln recognized, might to a degree be influenced by the leader.

Finally, as we stress at the Jepson School, leadership is persuasion: “When the conduct of men is designed to be influenced, persuasion, kind, unassuming persuasion ever be adopted. Such is man, and so must he be understood by those who would lead him, even to his own best interest.”

Dr. McDowell’s remarks were compelling reminders that good leadership is very much about the words — spoken and written — leaders use to inspire action that is consistent with self-interest and moral sense.