Recommendations

It is crucial to the United States health that as many civilians as possible receive vaccinations. The choice to get vaccinated is a decision holding the rest of society at stake. If people refuse to get vaccinated, they are threatening all of society by being susceptible to preventable diseases. In the cases of those who are not medically advised to get vaccinated because the vaccine itself is too harmful for that person, they rely on herd immunity to protect them from diseases. Although there are ethical arguments for the implementation of vaccines, this is only a short-term solution. An exemption-free implementation of vaccinations would increase herd immunity at the cost of angering those who believe in autonomy of body, endangering those who are medically unable to get vaccinations, and violating the constitutional right to practice freedom of religion. There are alternative solutions to get people to opt-in vaccinations. Stricter vaccination requirements in public spaces, incentives programs, and vaccination campaigns are effective methods of increasing vaccination rates. These solutions are better because they work long-term, and endorse an environment in which vaccinations are viewed positively.

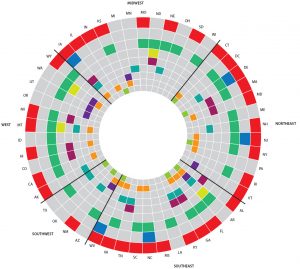

State laws already require children to receive vaccinations before entering public schools, exemptions varying from state to state. One way to increase vaccination rates is by changing (or sustaining, in some cases) all exemptions to only accept medical or religious excuses. Additionally, this policy could be implemented in offices, requiring employees to get vaccinated. By addressing schools and offices, the requirements apply to children as well as adults. Restricting exemptions has shown to be an effective method of increasing rates, such as in the case of Mississippi. Mississippi does not allow any personal exemptions, and they also have the highest vaccination rates in the US (Maron, 2015).

It is not reasonable to allow philosophical exemptions because they are not rooted in fact. A great number of people choose to opt-out of vaccinations because of misbeliefs on vaccinations. A myth about the MMR vaccine causing autism discouraged many parents from vaccinating their children. Even after this myth was debunked, parents continued to opt-out (Brownstein, 2014). These types of philosophical exemptions are harming the community, and therefore should not be permitted. In the case of Jacobson v. Massachusetts, the enforcement of smallpox vaccinations was debated. The court ruled that if it was harmful for certain individuals to receive vaccinations, those individuals have proper excuse to refuse vaccinations. However, in the case that someone is “in perfect health and a fit subject of vaccination, and yet, while remaining in the community” then they have an obligation to get vaccinated for the “protection of the public health and the public safety” (Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 1905). Not doing so is an endangerment to the community, and is a punishable offense. This case should be applied to all communicable diseases for which vaccines exist. The smallpox vaccination is a prime example of the effectiveness of vaccines and herd immunity. While a small percentage of people were not able to receive the vaccination, enough people received it to uphold herd immunity. Due to the utilization of the smallpox vaccine, “the World Health Assembly declared that smallpox has been eradicated from the earth in 1980” (Belongia, 2003). The eradication of smallpox is scientific (and historical) verification that vaccinations contribute to the wellbeing of society. Scientific evidence has repeatedly shown vaccinations to be an essential part of a community’s health. Therefore, any philosophical argument against vaccinations acts an excuse not to optimize the health of the community, and should allow for exemption. As long as vaccinations are tested to be safe, there is a miniscule amount of harm being done to those who have philosophical protests. The worst is perhaps a little prick and a sore arm, but this cost is reasonable to impose on somebody to protect the overall health of the community.

I believe that religious exemptions should still exist because even though scientific evidence has proven vaccinations to be safe (for non-medically-exempt people) and effective, it is a constitutional right to practice religion. Additionally, very few religions call for the refusal of vaccinations. Most religions do not only oppose vaccinations, but support the promotion of societal health by means of vaccinations. The main religions with opposition to vaccinations are Christian Scientists, who believe God will cure modern diseases, and the Dutch Reformed Church, which holds the belief that vaccinations interfere with their relationship to God. While Christian Scientists may not understand the necessity of vaccinations, the founder of the Church, Mary Baker Eddy, recommends that “if the law demand that an individual submit to this process, [then] he obey the law, and then appeal to the gospel to save him from bad physical results” (Krule, 2015). So, even though Christian Scientists do not agree with vaccinations, there is not an official refusal of vaccinations as part of their religion. As for the Dutch Reformed Church, they make up less than 1% of the US Population, so the refusal of vaccinations from this small population does not cause a significant drop in herd immunity. A study published in Clinical Infectious Diseases addresses herd immunity as “a particular threshold proportion of immune individuals that should lead to a decline in incidence of infection” (Fine, 2011). A 100% vaccination rate is not attainable, yet this “herd immunity threshold” is all that is needed to protect those susceptible to diseases. Without Christian Scientists and members of the Dutch Reformed Church, the US is still able to reach the herd immunity threshold. Therefore, it is okay to allow religious exemptions as they do not significantly affect US vaccination rates.

While mandating vaccines is one way to increase vaccination rates, it only applies to certain places (currently, public schools) and does not motivate civilians to continue vaccinations outside of those institutions. In addition to those requirements, an incentives program should be devised to reward those who get vaccinated. A program like this already exists in Australia, which has a 94% percent measles vaccination coverage rate for one-year-olds, beyond the US 91% coverage rate (Maron, 2015). The Australian government provides tax credits for parents whose children are vaccinated, which physicians receive commission when patients are vaccinated on schedule. An incentives program in the US will effectively motivate civilians to get vaccinations. Instead of seeing vaccinations as a burden, they become an opportunity to relieve finances. The incentives can come in the form of tax breaks, health insurance discounts, lowered prices for airlines, school supplies, etc. This program will be effective because people are not being forced to receive vaccinations, but doing so would benefit them.

Though it may seem unfair to those who are medically unable to get vaccinations, there remain opportunities to reap benefits from this program. For those who cannot receive specific vaccinations (perhaps in the case of allergies), they can still receive the credit for receiving the rest of the CDC-scheduled vaccinations. As for those who cannot receive any vaccinations due to compromised immune function, they can receive credit by starting, donating to, or participating in a vaccination campaign.

The final branch of the solution is a national vaccination campaign. A Dartmouth study has found that “repeated pro-vaccine messages from public health agencies can actually backfire by creating more resistance to immunization among those with firmly held anti-vaccination beliefs” (Maron, 2015). The resistance to listen to public health agencies may be due to the assertion of authority coming off as unsettling. To combat this, vaccination campaigns will be created by regular civilians who strongly believe in the importance of vaccinations. In a study published in Journal of Health Management, it was found that NGO’s are inclined to use a bottom-up approach to mobilize people. A bottom-up approach is characterized by “local decision making” and “community participation” (Panda, 2007). Through a bottom-up approach to vaccinations, more people in the community will be receptive to the ideas of their peers. A local, personalized campaign is more likely to impact a community than a general statement made by health officials saying that vaccinations are good.

These campaigns can also advise healthcare professionals in their communication with patients. Sometimes the difference between opting in and opting out is simply the way a physician offers the vaccine. A study in Pediatrics found that parents were more likely to get their children vaccinated if the shot had already been scheduled, indicating parents will most likely not refuse vaccinations if it is already expected (Maron, 2015). Additionally, the study found that parents are more likely to opt-in if it is more difficult to opt out, meaning they must go through a filing process to receive an exemption. The results of this study may give vital information leading to the rise in vaccination rates. It very well may be that parents make their vaccination decisions based on convenience. If this is true, and the overall objective is to increase vaccination rates, the next goal is to make opting-out a hindrance.

These campaigns aim to engender long-term participants of vaccinations by educating parents and students about vaccine effectiveness. These campaigns should be designed so that it makes getting vaccinated easier. They could travel to different schools and workplaces to offer education as well as the yearly flu-shot. While there are many anti-vaccination campaigns in existence, it is important to drown out the lies spread by those campaigns with the facts of vaccinations. While anti-vaccination campaigns use celebrity appeal, such as Jenny McCarthy, to spread awareness of their cause, science has exposed their lack of credibility. While the myths continue to disperse, it is more crucial than ever to have a campaign to counteract the damage they cause.

The solutions I have proposed of stricter exemptions, incentives programs, and vaccination campaigns should benefit communal health by raising vaccination rates in the US. It is important to remember the dangers that occur when vaccinations are not implemented. In clustered communities with low herd immunity, infections spread rapidly. Epidemics of polio, measles, and smallpox have all occurred due to the limited means of prevention. Now that safe, effective means of prevention (vaccinations) exist, it is crucial that as many people as possible utilize vaccinations and protect their community from disease outbreaks.