Ethics

I argue that it is morally good to require vaccinations in the US. Without vaccinations, the US is at risk of a harmful epidemic, so the implementation serves to protect the population as a whole. Health is an important issue in the United States, and history has shown that vaccinations are a crucial part to the health of the world, today. The decision to require vaccinations is significant because it affects the entire population of the US. When assessing the implementations of vaccines, it is logical to consider the health implications of the country- lowered herd immunity, increased chance of contraction, and risk of epidemics- if vaccines were not used, as well as the obligations of society to take preventative measures against those consequences. The arguments against the implementation of vaccinations- there is possible harm caused by vaccinations, it is unnecessary to mandate, parents make the best decisions, and it is a violation of rights- are considered and rebutted. The primary ethical consideration for mandatory vaccinations in the US are that there is a communal obligation to ensure the safety of the population when the health of the nation is in jeopardy such that it is the parental responsibility to immunize their children. These ethical stances lead to the support of mandatory vaccinations as it is the most ethical solution to solve the vaccination debate in the US.

When the health of our nation is in jeopardy, society has a social responsibility to protect the nation as a whole. Thomas Hobbes’s Social Contract theory states that by entering a society, there is an implicit agreement to “renounce the rights they had against one another in the State of Nature” (Social Contract Theory). The social contract asserts that civilians have an obligation to cooperate within society in order to benefit from society by living with regards to one another. Using the social contract theory, it can be argued that citizens are obligated to get vaccinated as it promotes the greater good of the nation by promoting health. Janet Stemwedel, a science ethics professor at San Jose State University, argues that “under such a social contract, we as a society have an obligation to take care of those who end up paying a higher cost to achieve the shared benefit” (Stemwedel, 2013). According to Stemwedel, the cost of diseases is more significant than the cost of vaccinations, and therefore those who are able should feel inclined to pay the lower price. If individuals do not receive vaccinations now, then society as a whole will pay the price of harmful epidemics. It is unjust for people to benefit from others’ vaccinations if they are able to, yet not, being an active participant in the effort to eradicate diseases. If one person does not act in accordance with the social contract, they are regarded a “free-rider” (Stemwedel, 2013) and thus make no societal contribution. For whatever reason a person chooses to opt-out of vaccinations, they can only contribute by restricting access to the community, particularly those which include the medically-exempted. Additionally, Stemwedel argues “[parents and kids] are accountable to other members of that community” (2013). Stemwedel reiterates the social contract theory, saying that the people part of a community are responsible for the stake of the community. In this context, that means preventing diseases as a community by getting vaccinated.

Since there is an obligation to protect the community, then actions to preserve the community’s safety are morally good. The consequentialist argument here is that if getting vaccinated can prevent an epidemic, then one should get vaccinated. The consequences of getting vaccinated are positive, while refusing vaccination has negative consequences. Vaccination promotes the community’s bond by exemplifying cooperation within society and consideration for others. By getting vaccinated, one is participating in the preservation of health. By refusing vaccinations, a spread of disease is probable. Consistent reports of a correlation between lack of vaccinations and spread of disease exemplifies that there is a causative effect. One instance is the 2010 Pertussis outbreak in California. A study published by the American Academy of Pediatrics found significant association between Non-Medical Exemptions (NMEs) in 2010 and pertussis cases, suggesting “clustering of NMEs may have been 1 of several factors in the 2010 California pertussis resurgence” (Atwell, 2013). The California pertussis epidemic is one example of a decrease in vaccination rates leading to an epidemic.

Motivation to benefit the community does not come from the social contract, but rather it comes from the fact that benefiting the community benefits one’s self. Not only is benefiting the community inherently good, but by an egoist perspective, it is morally good because it serves the self. This happens because the consequences of vaccinations are reduced risk of disease. By not protecting oneself against diseases, one is constantly at risk of contracting the illness as well as spreading the illness. It is obvious that vaccinations benefit the individual who receives them. For these reasons, it is inherently good to benefit the self, and is morally acceptable from an egoist perspective. Additionally, a Harvard University study concluded that “Lowering stress levels over a period of years could reduce [the] risk of health problems” (Harvard Health Publishing). It is fair to make the assumption that one may stress about the possible contraction of diseases. It is also safe to infer that vaccinations would lower the recipient’s stress about contracting diseases. Therefore, it can be concluded that because vaccinations lower stress, they also lead to a happier lifestyle. A hedonist would argue that it is morally good to do things that feel good, and since being happy is feeling good, it can be considered a moral good. Accordingly, getting vaccinated is also morally good from a hedonist’s perspective.

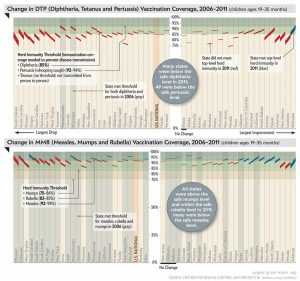

Speaking to the communal obligation to ensure the safety of the population, it is the responsibility of parents to immunize their children. It is a normative statement that children look to parents for protection. Because getting children immunized is a form of protection, parents are obligated to get their children immunized. It is the parent’s duty to do what is best for their children. Dr. Stemwedel argues that parents “have a duty to do what is best for [children], as well as they can determine what that is” (2013). The information with which parents are supplied generally support the decision to get their children immunized, so it is only logical that parents follow through with immunization. The Center for Disease Control recommends every child receives vaccinations provided the child is not allergic to any of the ingredients. The CDC even outlines a schedule of vaccinations recommended for parents. Additionally, the CDC published a graph depicting a decrease in DTP and MMR vaccinations in 2011 (Fischetti, 2013).

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/too-many-children-go-unvaccinated/.

The consistent drop is due to parents opting out of vaccinations for their children. William Schaffner, chair of preventative medicine at Vanderbilt University asserts that the reasons for opting out are not science-based (Fischetti, 2013). Given that parents are not relying on scientific evidence, it can be reasoned that the parents opting out are not necessarily doing what is best for their children because sometimes decisions go against fact. Since the CDC is an expert source on the topic of vaccinations, it cannot be argued that parents are not able to make an informed decision about vaccinations because they are given all information needed. After a rumor spread that a British study found a link between vaccines and Autism, parents became hesitant to vaccinate their children. The Autism link has been debunked, yet while parents were less likely to think vaccines caused autism, they were also “less likely to want their children to be vaccinated after being educated” (Brownstein, 2014). The fact that parents knowingly disregarded new found scientific evidence on the safety of vaccinations stands as a testament to the obstinate nature of parents who choose to opt out. This is important because it means that just correcting information is not enough to change their minds. It is parents’ responsibility to take care of their children by normative reasoning. Since the responsible thing to do is get children vaccinated, vaccinating children is fulfilling parental duties.

A counter-argument for government-mandated vaccinations is that parents know what is best for their children. Governor Chris Christie is quoted saying, “it’s much more important what you think as a parent than what you think as a public official” (Mirsky, 2015). In this statement, Governor Christie is emphasizing the role parents play in their children’s lives and insinuating their knowledge on their children surpasses the expertise of the government. It has already been argued, however, that sometimes parents do not make the best decisions for their children, so this counter-argument can be ignored.

Relating back to the health of the nation, it is a normative statement is that health is good. Vaccinations are essential as they promote herd immunity, the notion that when enough people are protected from a certain disease, the likelihood of a community contracting that disease is reduced overall. Stemwedel credits herd immunity to the unlikeliness of the spread of measles (2013). Promoting herd immunity is reducing the chances to spread diseases among a community, which is promoting health. Preserving the herd immunity of the country is a deontic good. There also is a consequentialist argument for vaccinations as herd immunity is one positive outcome of vaccinations. Since a consequence of vaccinations is herd immunity, and herd immunity is good, it can be concluded that vaccinations are morally good from a consequentialist perspective. Additionally, promoting herd immunity participates in the social contract because it is an effect on the community as a whole. Some people cannot receive vaccinations because of medical reasons (allergies, poor immune systems, age limits), so they rely on herd immunity for protection against diseases. Herd immunity does not occur on an individual basis, but rather it occurs when a large enough sect opts for vaccinations. Stemwedel argues that if people are not willing to do their part for herd immunity, then they are responsible for dissociating from the community (2013). Stemwedel makes a fair statement because the social contract is a give-and-take agreement. By contributing to herd immunity, one is acting in accordance with the social contract.

Owing to the fact that implementing vaccinations affects everyone in the community, one family’s decision to not vaccinate can cause harm to other families. The consequentialist argument is that by getting vaccinated, one consequence is not harming other families through the spread of disease. Normative reasoning can also be used to assert that it is morally wrong to inflict harm on others. While choosing to vaccinate does not hurt others, opting out can harm others.

Deontic reasoning promotes vaccinations because the refusal of vaccinations is not universally good. One may not care if others are harmed because of their decision to opt out, but undoubtedly, they would care if they suffered the consequences when others opted out. It cannot be concluded that opting out of vaccinations is universally good because one naturally does not want to be subjected to hardship caused by other people. Because harming others is inherently bad, opting out of vaccinations is morally wrong.

There is hesitation to support the legal mandating of vaccinations because of anxiety about the outcomes. A common belief is that the government intends to enact laws that do more harm than good, like permitting the usage of potentially harmful ingredients in medicines. In France, general practitioners argue that “the measure is authoritarian” in a country with widespread “mistrust of health authorities” (Laws are Not the Only Way to Boost Immunization, 2018). This mistrust stems from various health scandals such as HIV-infected blood transfusions in the 1980s. Though there may be evidence supporting malpractice at one time, regulations have since been put in place to prevent the consequences from occurring again (i.e. screening blood for HIV). Generally, healthcare advising should be trusted because it is the CDC’s goal to protect people and save lives just as it is the government’s interest to protect civilians because in a democracy, the government has no power without support of the people. There is good reason to believe that the government, and healthcare professionals, would make decisions with good intentions. Mandating vaccinations is morally good by instrumental means; the intentions of the government is to preserve American health.

It can be argued that government regulations are unnecessary because the market for vaccinations will regulate itself. In this case, the market regulation is more of a call to Darwinism, or survival of the fittest. This argument is rather simplistic because it presumes that one’s refusal to vaccinations will not affect others, the strongest will not be affected by disease, and the ones who choose to get vaccinated are the only ones that deserve to be healthy. These allegations are false as it has been established that opting out of vaccinations does affect others and the strongest can still be infected by disease, and it is preposterous to propose that certain people have more of a right to live than others by universalistic beliefs. Taking a universalist stance, everyone has the equal warrant to health and life. Also, by the time the “market” regulates, the consumer population could have drastically diminished.

The most worthy argument against government mandated vaccinations is that it is an infringement on individual rights. Senator Rand Paul expressed his agreement of this view on CNBC, claiming that vaccinations should not be required because “the state doesn’t own your children. Parents own the children. And it is an issue of freedom and public health” (Mirsky, 2015). Parents own the children in a sense that they are responsible for making health choices for them. Many people agree that the government does not have a right to control a civilian’s body because of the ideology autonomy of body, and the requiring of vaccinations is doing exactly that by forcing a change on someone’s body. This is countered by the social contract theory, as it outlines that individual rights may be sacrificed for the greater good of society. Mandating vaccinations improves the community and raises the standard of living. Stemwedel owes the fact that most members of society are vaccinated means that “there is a much less chance that epidemic diseases will shut down schools, industries, or government offices” (2013). To risk the chance of an epidemic is to gamble society’s overall welfare. Furthermore, a consequentialist view concludes that although the reduction of freedom itself is bad, the consequences of doing so are good, and therefore it is morally acceptable to restrict freedoms in this case.

It can also be argued that requiring vaccinations is not truly restricting freedoms. In the case of state-required vaccinations, there exist exemptions, which allow parents and participants to deny vaccinations on the basis of medical, philosophical, or religious restrictions. I argue that with these exemptions, there is no violation of rights. Exemptions allow people to get out of vaccine requirements, so a loophole exists even in the case of legally-mandated vaccinations. Because of exemptions, it is not immoral to legally require vaccinations.

Nationally requiring vaccinations is not a permanent solution to the public health crisis in America, though. There will be resistance against it because of mistrust in government and medical corporations. The implementation of vaccinations should result in vaccination effectiveness. Until everybody is on board with vaccinating to preserve the health of the nation, there will not be full cooperation, and therefore the health of the nation will not be optimal. Without full cooperation there is no progress.