The opponents to the argument about drinking age law’s negative consequences argue that the current drinking age saves lives by preventing alcohol-related traffic fatalities among young Americans. They cite studies that show that motor vehicle accidents decreased during the same time period as the change of the drinking age from eighteen to twenty-one.

Morris E. Chavetz, a member of the Presidential Commission on Drunk Driving and the chair its Education and Prevention Committee in the 1980s, points out the flaw in this argument. Although Chavetz voted “yes” to raising the drinking age to twenty-one, and regards his choice as “the single most regrettable decision of [his] entire professional career” (Chavetz). Chavetz raises the crucial point that while the drunk driving traffic fatalities are lower than they were in 1982, “they are lower in all age groups. And they have declined just as much in Canada, where the age is 18 or 19” (Chavetz). The studies claim to prove that raising the drinking age to twenty-one reduced traffic fatalities. Chavetz declares, “it has been argued that ‘science’ convincingly shows a cause-and-effect relationship between the law and the reduction in fatalities…but correlation is not cause” (Chavetz).

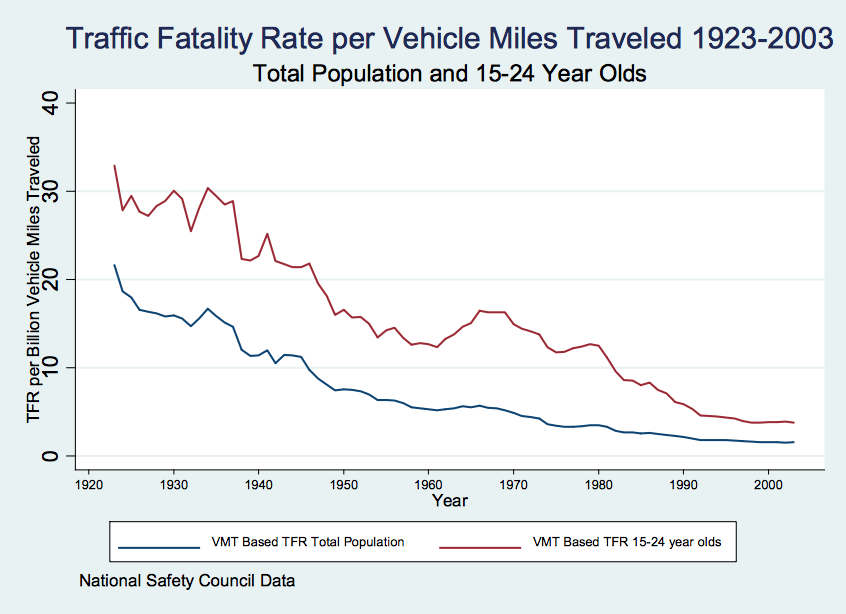

As researchers Jeffrey Miron and Elina Tetelbaum point out, traffic fatality rates have been “decreasing steadily since 1969, but most of the variation in the MLDA occurred in the 1980s. The one major increase in traffic fatalities, from 1961-1967, occurred while the average MLDA remained constant” (Miron 7).

Figure 3, Miron and Tetelbaum

This finding suggests that raising the drinking age was not the cause of the decrease in traffic fatalities. The greatest reduction in traffic fatalities actually are attributed to advances in medicine, technology and car design, and education about “driving strategies and the risks associated with motor vehicles” (Miron 7). Thus, the presumed causation between the MLDA of twenty-one and the reduction of traffic fatalities is fallacious. The argument that lowering the drinking age would cause an increase in alcohol-related traffic fatalities among young Americans is invalid, for drinking-related traffic fatalities have been decreasing due to factors independent of the drinking age law for decades.