The latest from Legendary Heroes By Scott T. Allison and George R. Goethals, authors of Heroes: What They Do and Why We Need Them

With Columbus Day fast approaching, we've been encouraged to write about Christopher Columbus and his unsurpassed impact on the world we live in today. Recently, we proposed a distinction between a hero or villain whose influence on the world is very short-lived (an ephemeral or transitory figure) and a hero or villain who forever changes an entire society (a transforming figure). Whether you believe his impact to be positive or negative, Christopher Columbus and his 1492 voyage to the Americas left an indelible mark on nearly every corner of the globe.

Transforming events do not take place in an historical vacuum. To understand Columbus's motivation to establish a shipping route to Asia, we must look to the city of Constantinople, now Istanbul, Turkey. For centuries, as the capital of the Orthodox Christian Byzantine Empire, Constantinople had been an important center for trade between Europe and Asia. But in 1453, the Muslim Ottoman Empire conquered Constantinople, forcing Europeans to search for a sea route to Asia that would bypass the Muslims.

Transforming events do not take place in an historical vacuum. To understand Columbus's motivation to establish a shipping route to Asia, we must look to the city of Constantinople, now Istanbul, Turkey. For centuries, as the capital of the Orthodox Christian Byzantine Empire, Constantinople had been an important center for trade between Europe and Asia. But in 1453, the Muslim Ottoman Empire conquered Constantinople, forcing Europeans to search for a sea route to Asia that would bypass the Muslims.

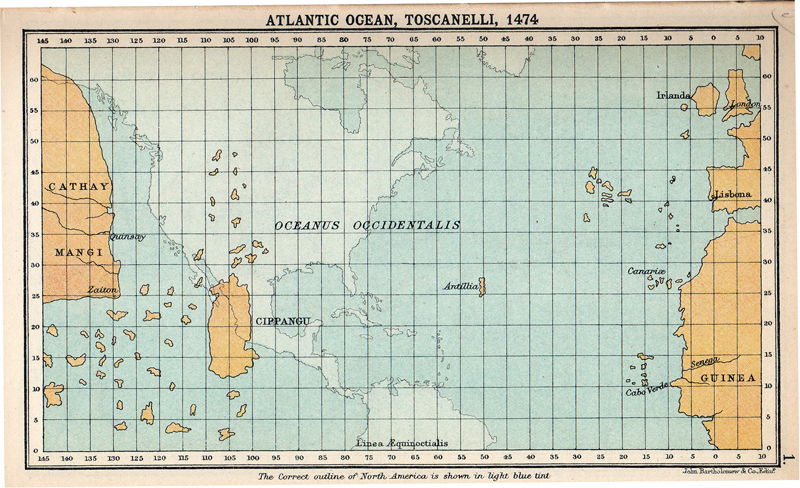

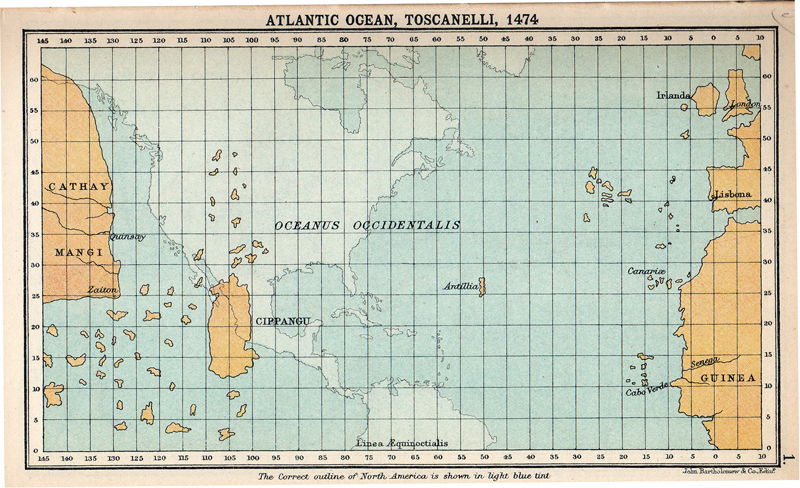

Interestingly, Columbus may never have attempted his initial voyage had he not held several misconceptions about global geography.  He underestimated the circumference of the earth; he overestimated the size of the Asian landmass; and he believed that Japan lay much farther east of China than in reality. He did, however, have an accurate understanding of the prevailing easterly trade winds that would propel his ships from the Canary Islands to lands far to the west. With about 90 men and sailing under the flag of Spain, Columbus's three ships were fortunate to avoid both tropical storms and the "doldrums" €” pockets of sea where there is neither current nor wind.

He underestimated the circumference of the earth; he overestimated the size of the Asian landmass; and he believed that Japan lay much farther east of China than in reality. He did, however, have an accurate understanding of the prevailing easterly trade winds that would propel his ships from the Canary Islands to lands far to the west. With about 90 men and sailing under the flag of Spain, Columbus's three ships were fortunate to avoid both tropical storms and the "doldrums" €” pockets of sea where there is neither current nor wind.

Most of us know the rest of the story. On October 12, 1492, Columbus and his men landed on the island of Guanahani, and called it San Salvador. Although he failed to reach Asia, Columbus made the western hemisphere known to Europeans, forever altering human history on a global scale. Until very recently, generations of Americans grew up learning that Columbus "discovered" America – a Eurocentric notion that ignored the presence of 50 million indigenous people inhabiting the Americas in 1492. Moreover, other Europeans, such as the Norsemen, had ventured to America 500 years earlier. "Columbus's claim to fame isn't that he got there first," explains historian Martin Dugard, "it's that he stayed."

The heroic interpretation of Columbus is that his daring voyage into unknown waters required courage and conviction. In 1989 U.S. President George H. W. Bush said that Columbus "set an example for us all by showing what monumental feats can be accomplished through perseverance and faith."  Extraordinary changes resulted from Columbus's voyages. The Columbian Exchange was established, referring to the two-way transfer of culture, foods, plants, and animals between the continents of Europe and the Americas. The Americas were introduced to crops such as wheat, rice, coffee, bananas, and olives, and animals such as horses, cows, pigs, and chickens. Europeans also received from America many important crops, such as corn, potatoes, tomatoes, lima beans, squash, peanuts, cassava, cacao, and pineapple.

Extraordinary changes resulted from Columbus's voyages. The Columbian Exchange was established, referring to the two-way transfer of culture, foods, plants, and animals between the continents of Europe and the Americas. The Americas were introduced to crops such as wheat, rice, coffee, bananas, and olives, and animals such as horses, cows, pigs, and chickens. Europeans also received from America many important crops, such as corn, potatoes, tomatoes, lima beans, squash, peanuts, cassava, cacao, and pineapple.

The past few decades have also seen Columbus cast into the role of villain. Deadly European diseases were introduced into the Americas, including diphtheria, measles, smallpox, and malaria. The Americas, in turn, contributed a virulent form of syphilis to Europe. All told, Native American populations suffered to a much greater degree than did Europeans. Epidemics wiped out 80 to 90% of the native populations in Hispaniola, and European settlers enslaved many Native Americans. In fairness to Columbus, the worst of these problems occurred after he died, under the watch of later European governors and colonists.

In preparing this blog post, we googled "Christopher Columbus hero villain" and obtained over 100 websites debating Columbus's status as hero or villain. It's clearly a muddied picture. All we can say with certainty is that Columbus's voyages had a permanently transforming effect on the world. "Every hero is somebody else's villain," said Felipe Fernandez-Armesto, a scholar and author of several books related to Columbus, including 1492: The Year the World Began. "Heroism and villainy are just two sides of the same coin."

One of our readers suggested that we profile Christopher Columbus. We welcome your suggestions as well. Please send your ideas to Scott T. Allison (sallison@richmond.edu) or to George R. Goethals (ggoethal@richmond.edu).