The Tortoise and the Hare’s Ultimate Race

(photo by Lauren at Shining Lamp and Brilliant Star)

So there I was: third grade and as nervous as I had ever been. It was the fifth week of school and I was still stuck on my multiplications of three. Why couldn’t I get it? My teacher told me I was smart. Shouldn’t I have been able to know how to count by threes? Why did it take me so long while everyone else finished within sixty seconds? I yelled at myself; I’m stupid and I’ll never get to multiplications of four! I’m just not smart enough.

In the second chapter of the book, Why Aren’t More Women in Math and Science, Carol S. Dweck takes on the role as the neutral researcher. Her expressed goal was not to determine distinct differences between male and female and how those differences correlate with success but to determine what intellectual factor in all human beings galvanizes the determination to succeed. She expresses, “what we are looking at here is not a difference in ability, but a difference in how students cope with experiments that may call their ability into question—whether they feel challenged by them or demoralized by them” (Dweck 48).

After reading Dweck’s essay, I began to understand that any research can be done to support a specific argument. So when trying to answer a controversial question such as: Why Aren’t More Women in Math and Science?, it is important to look at the larger picture and think about more factors than just one. Dweck’s research not only answers why less women are in math and science but also answers how women who DO succeed in math and science think, and how men who are in STEM think. I didn’t realize the importance of understanding how the mentality of a student affects his/her learning ability. Dweck’s research outlined that “viewing intellectual ability as a quality that could be developed led them to seek active and effective remedies in the face of difficulty” (Dweck 48). If teachers taught students from the start that ability is something to be earned, the ratio of successful males in math and science to successful females in math in science would be closer to 1:1.

I’ve always had difficulty learning mathematic concepts. In third grade I was really hard on myself because I wasn’t comfortable with how much work I had to put in to learn. I hated to be a slow learner and I frequently gave up. It wasn’t until junior high that I developed an appreciation of learning. Challenging new concepts intrigued me and I begged for more. I began to actually search for problematic subjects to study. Easy went from covetable to mundane. Even now, in college, I search for challenging courses. I can’t count the many times people stare at me with dismal eyes and wish me luck as I express my desire to go to medical school. “That’s hard” they say. The challenges and promise of new and exciting information is what keeps me going because like all other lessons in life, math ability is something that reaches fruition through effort” (Dweck 52).

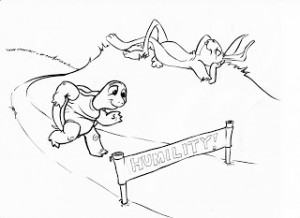

In a lot of cases, the people who are the most talented or are considered to have the highest IQ are not the people who achieve the most success. Take the well-known childhood story, the Tortoise and the Hare, for example. During the race, the hare, who had natural speed and longer legs than the tortoise, took his time and arrogantly tormented the tortoise’s slow pace by taking naps and reading books. But the tortoise who obviously was considerably slower than the hare took his time, and remained humble no matter what. The tortoise’s determination and perseverance allowed him to win the race. So we see, it is the people who are most hardworking that accomplish the most.

Resources Cited:

Lauren. “Shining Lamp and Brilliant Star.” : The Tortoise and the Hare: Coloring Book Page. Blogspot, 05 Jan. 2011. Web. 08 Sept. 2015.

Dweck, Carol S. “Is Math a Gift? Beliefs That Put Females at Risk.” Why Aren’t More Women in Science?: Top Researchers Debate the Evidence. (2007): 47-55. Web.