Nature Is Not Evil

by Lillie Mucha

My vaguely-considered curiosity presented in response to the previous chapter – “it is important to recognize that the physiology and hormones in males and females are different” (Mucha 2015(a)) – was greatly expanded on after reading the essay “Taking Science Seriously: Straight Thinking About Spatial Sex Differences” by Nora S. Newcombe. I had been assuming that sex differences are essentially bad, and idea based on multiple occurrences of hearing arguments about the (not really) all-important difference in math testing scores for females and males. It seemed logically at the time that the difference must be a bad thing to cause so much controversy. The explanation I thought was that either women were not as smart as males or the men were unfairly dominating the world of science. I believe now that sex differences are natural, though magnified by inaccurate stereotypes that can breed a crucial lack of understanding about the meaning of male and female.

The Arguments for Natural Sex Differences

A meadow vole chewing on grasses

In “Taking Science Seriously,” Newcombe presents the argument that, while possibly caused by sex hormones, sex differences are not supported evidence to have developed through evolution because of any reproductive advantage. She claims that the “Man the Hunter” (men must track and hunt animals for survival) and “Man Who Gets Around” (like meadow voles, men must travel to reproduce) theories are inadequate to explain why greater spatial ability would have helped prehistoric males survive and impregnate the females. In addition, she says that since higher spatial ability has benefits for both sexes but no apparently significant advantage for males in comparison, there is no reason why both sexes would not develop the skill. Since hormone levels are related to spatial ability, but the ability cannot simply be explained as “male hormones promote it and female hormones restrict it”, Newcombe suggests that the sex difference in cognitive ability is simply a secondary trait of the necessary sex-specific hormones.

Newcombe does not take the “extreme ‘nurture’ position: that males and females are biologically indistinguishable, and all relevant sex differences are products of socialization and bias,” as defined by the evolutionary psychologist Steven Pinker (Pinker & Spelke 2005). While Newcombe does disagree with Pinker’s speculations regarding the evolutionary aspect of sex differences, the two agree that sex differences do naturally occur. Many studies show the apparent difference in sexes for cognitive abilities, especially related to hormone levels (Halpern 1997; Hausmann et al. 2000; Lenroot & Giedd 2010). I agree with the statement made by Doreen Kimura, that to believe sex differences do not exist “is basically incompatible with scientific principles, because it encourages the ignoring of a large body of opposing research” (Kimura 2007). By focusing only on the convergence of male and female scores as infants or elementary school children, the important sex-related period of puberty is incorrectly construed as being an unnatural influence.

“Natural” is Transformed into Something Else

The biology of the sexes is a relevant and realistic understanding of how sex differences come about. Unfortunately, stereotypes about the differences between men and women also exist, and complicate the matter significantly. As it has been introduced in the book before, teaching and learning mindsets play a large role in how stereotypes manifest in the abilities of men and women (Mucha 2015(b)). The biological differences between males and females are not inherently bad, but when they are unnaturally magnified by gender stereotypes, the opportunity for discrimination snowballs.

Sources

Kimura, D. (2007). “Underrepresentation” or Misrepresentation? In Ceci, S. J. & Williams, W. M. (Eds.), Why Aren’t More Women in Science? (pp. 39-46). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Newcombe, N. S. (2007). Taking Science Seriously: Straight Thinking About Spatial Sex Differences. In Ceci, S. J. & Williams, W. M. (Eds.), Why Aren’t More Women in Science? (pp. 69-78). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Print.

Diligent Analysis of Sex Differences

alternatively titled: “How Many Discussions does it take to Challenge an Assumption?”

by Lillie Mucha

Elizabeth S. Spelke and Ariel D. Grace respond to the debate over Lawrence Summers’ comments with a deep understanding of the assumptions his statements have implied. In their essay, “Sex, Math, and Science,” they explain the empirical behind the belief that males and females have no sex differences that would explain the difference in employment in science. Citing studies of primarily infant cognitive abilities, they say that the sexes are equal in ability. I agree with Spelke and Grace’s position that discrimination is more to blame for the lack of women in science than biology is. In our age of emotionally and politically founded arguments, an explanation with good analytical depth is hard to come by through popular media. What we think of as getting deep into a discussion can often be not deep enough. So let’s discuss.

Various Gender Labels

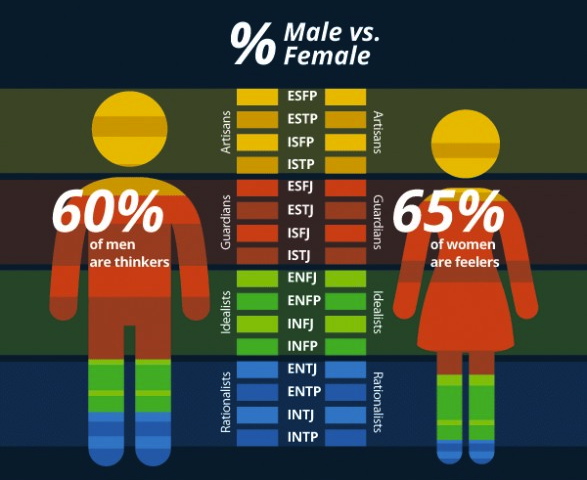

I was immediately drawn to the gender argument of “systemizers” and “empathizers” (58). The theory generally states that males are innately “systemizers,” or people who are better at learning mechanical patterns, and females are innately “empathizers,” or people who are better at learning emotional patterns. This theory reminded of the gender difference present in Myers Briggs Type Indicator. In one study, only 30% of female teenagers identified as Thinking types, while only 40% of male teenagers identified as Feeling types (Bayne 1997). This falls in line with gender stereotypes we are overexposed to.

Directly in contradiction to this assumption, Spelke and Grace supported the idea that males and females are cognitively the same in infancy, a time in which social constructs have had very little time to make a difference on the child’s expressions (58). It’s an important step to take in studying infants. By the time participants are adolescents, their brains have developed in many new ways. They have been exposed to gender norms for over a decade, and puberty has started to affect their development in sex-specific ways. Spelke and Grace go on to say that older children do tend to approach problems differently: males more often use geometry and spatial reasoning skills while females use landmarks and algebra skills to do the same tasks (59).

Multiple Kinds of Bias

At this point, the gender bias starts to make a significant difference. Since math problems can be solved two ways, and either could be more effective than the other on any given problem, the possibility that the answers to tests are written with a male cognitive advantage is very likely. According to Spelke and Grace, the male-favoring difference on the Math SAT test is a poor predictor of female ability in college compared to males’. However, the work cited for this information did not conduct an experiment to determine this result, and I can imagine a compounding variable that could be in play: college enrollment.

The assumption is that women who are equally qualified but scored lower than men on the Math SAT are earning equal grades and bachelor’s degrees in college as men. While SAT test-takers are certainly intending on applying to college, there are some – usually on the low end of scores – who end up not applying or not being accepted. What would influence a test-taker not to apply to college? Female people significantly underrate their level of competence in a situation dominated by successful males (Correll 2004). A female low-scoring test-taker would more likely believe that they aren’t cut out for college, reflecting on both their decision and dedication to apply to colleges and universities. Also, people give evaluations with inherent gender bias against females, even if unintentional, as was shown by many studies in Spelke and Grace’s essay.

Summary

As for myself, I became aware of the fact that Spelke and Grace’s constant use of the phrase “no sex difference” led me to start thinking that males and females are truly identical. However, it is important to recognize that the physiology and hormones in males and females are different. How much this has to do with differences and similarities in the brain I do not know, but I am looking forward to exploring this topic in more detail in the next chapter, “Taking Science Seriously: Straight Thinking About Spatial Sex Difference.”

Sources

Image source: link

Comparative Essay 1 Revision 1 (Lillie Mucha)

Greater Understanding of Gender Differences

by Lillie Mucha

Some research on Carol S. Dweck led me to confirm that she was the first researcher to coin and popularize the fixed mindset and growth mindset theories (Popova, 2014). It was very helpful for me to read about these theories from the original researcher. After reading “Is Math a Gift? Beliefs that put Females at Risk” by Dweck, a lot of my own opinions about sex differences and stereotypes were refined. I strongly believe that the mindset theories help explain a significant part of the debate over women in science.

Dweck’s Research

Dweck explains that her research on children’s reactions to challenges helped her to notice a trend among bright female participants. The higher a female participant’s IQ score, the worse she performed on the challenging task. In comparison, “the higher [a male participant’s] IQ, the better they learned” (47). Since the bright female participants did much better when the task was not as confusing of a challenge, Dweck reasoned that what was influencing the participants was not a poor ability but a flawed mindset.

Dweck’s next interest was to find the root of the problem, in an attempt to change it (48). Her idea was that in a fixed mindset, people thought of intelligence as a constant ability that was either theirs or not, whereas in a growth mindset, people thought of intelligence as maleable and developed (48). Studying the theory further, she determined that two groups of females experienced different changes. Those who learned with a fixed mindset experienced the stereotypical gender gap in which males outperformed them, but those with a growth mindset performed just as well as the males in their grade. Further studies showed that fixed mindsets can make one more vulnerable to conforming to stereotypes (50), but education about the brain and mindsets can significantly reduce the gender gap between male and female students as it emerges in the beginning of high school (51).

Framing My Opinion

This reading gave me a lot of information. Before reading the essay, I was under the impression that a fixed mindset is bad and a growth mindset is bad, and that more female people develop fixed mindsets and more male people develop growth mindsets. However, those aren’t the implications that I got from the research now. It seems that both men and women can develop each kind of mindset, but the way in which it interferes with their life is different.

For females, some stereotypes I’ve heard often are that they are more emotional, are expected to work raising children, and are friendly. For males, the opposites often apply: more logical, expected to work making money, and are imposing. It is sensical that when one believes that peoples’ abilities are neatly placed in boxes, it can be easier to feel like you yourself are being placed in a box. I think it’s critical to understanding the issue of women in science to understand that mindsets influence people’s performance.

Works Cited

Popova, Maria. “Fixed vs. Growth: The Two Basic Mindsets That Shape Our Lives”. Brain Pickings. 29 January 2014. Web. 9 September 2015. <http://www.brainpickings.org/2014/01/29/carol-dweck-mindset>

Image source: link

Comparative Essay 1 (Lillie Mucha)

Only the Top Scores Matter

by Lillie Mucha

“‘Underrepresentation’ or Misrepresentation,” an essay by Doreen Kimura, introduced a new opinion to me. With supporting evidence, she claims that the math and science fields have not been discriminating against women, but rather women have a lower aptitude and lower interest in the sciences. She claims this is a natural, biologically-based deviation, and efforts to “artificially raise the numbers of women in science” are irrational.

“‘Underrepresentation’ or Misrepresentation,” an essay by Doreen Kimura, introduced a new opinion to me. With supporting evidence, she claims that the math and science fields have not been discriminating against women, but rather women have a lower aptitude and lower interest in the sciences. She claims this is a natural, biologically-based deviation, and efforts to “artificially raise the numbers of women in science” are irrational.

Biological predispositions

I agree with Kimura’s statement that the sexes are gifted with different levels of ability with regards to specific cognitive tasks. Evidence supports that a biological difference between the composition of the sexes does account for a consistent, reasonable difference between the average female and average male.

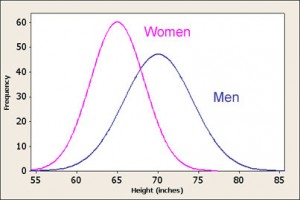

There is a slight inconsistency in Kimura’s words that I would point out: an entire paragraph is devoted to explaining that the, “[c]ognitive differences between men and women vary greatly in magnitude,” but in the conclusion Kimura states that there is “substantial overlap between men and women on all cognitive functions.”

Why the sudden change? To my understanding, the essay focuses largely on “men and women at the high end” of scores, reasoning that the top scorers will naturally go on to work in math and science and earn doctorates. What I think this approach does is totally ignore the males and females who are not at the top of high school math tests, but do go on to lead successful careers in math and science.

Does the data actually fit the pattern?

“The pattern fits well,” is what Kimura says about the varied distribution of women earning degrees in specific science fields as compared to their “math talent” and interest levels, but provides no evidence to support this theory. While biology may very well be a factor of the trend of women in science, I’m interested to know if there have been any experiments to test this pattern. Since there is “substantial overlap between men and women on all cognitive functions,” one would expect that there would be substantial overlap in the employment and interest of math and science fields.

What I think this reasoning brings to light is the idea that top scorers on math tests are not the only people who go into math and science. Similarly, the closer-to-average scorers don’t exclude math and science from their options. There seems to be an assumption that anyone who has ability should work in that field, but this approach doesn’t take into account the passion and dedication to learning of people who start with lower test scores. A lot of the people who go into math and science fall within the “substantial overlap” area. Considering this, is it really so reasonable that women make up 24.8% of computer and mathematical occupations in the U.S. (U.S. Department of Labor, 2009), yet 50.8% of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010), or is some other factor contributing to the trend?

The Other Factor

Of course, the name of the other factor most under question is discrimination. It shouldn’t be worrying to us that males and females aren’t represented equally just because we want the numbers to show a perfect 50/50 divide. There should be room for variation based on biological differences which do exist, and the slight back-and-forth shifting in numbers between the years. The importance is not in the numbers, but in the implications behind the numbers.

Are females underrepresented in math and science purely because of biological differences? If so, how can a “significant overlap” explain the 3:1 male-to-female ratio in computer and mathematical fields? Are gender discrimination and social constructs of the old days – stretching back not “over the past 2 decades,” but over multiple centuries – keeping women from pursuing and excelling in fields they would otherwise enjoy?

Sources

U.S. Census Bureau, 2010 Census of Population, Profiles of General Demographic Characteristics.

Image source: link

What is a Gender Spectrum?

By Lillie Mucha

The difference between gender as a spectrum versus as a binary construct is one that is very close to me. I’ve known for several years that I don’t fall perfectly into the category of a “stereotypical female,” and I suspect that nearly every girl feels the same way. Virginia Valian in “Women at the Top in Science – and Elsewhere” brings to light the harmful effects of establishing male and female stereotypes – “gender schemas” – that attempt to polarize these two groups of humans.

The Spectrum vs. the Binary

Schemas are of course necessary for social interaction to occur productively, since they can be highly useful in understanding a situation in the world. It would be very difficult to operate in the world if one didn’t have an understanding of the schematic differences between a fifteen-year-old and a fifty-year-old person. However, in the case of gender, people cannot be categorized so neatly.

The first thing to understand is that gender is not equal to sex. An individual’s sex is determined by their genitalia, and they can be male, female, or intersex, and with modern surgery can change their private parts to match their gender. Having any type of sexual organ does not automatically place a person’s gender, which is why communities of transgender gender people exist.

While it is a step in the right direction to understand that people are not 100% female and 100% male, this still gives the false impression of a binary gender system, in which men and women are judged based on their displacement from the average man and average woman.

There is no average man. There is no average woman.

These fictional people have been produced from the media, social norms, historical representations, personal encounters, and every other human influence. If we were to pretend for a minute that they never did exist, then it would become obvious that the range of human identities is of a much larger scope than the two standards we see so often today.

Gender and Science

There is a misconception about the science fields that I myself had to overcome. I thought of science as an alien world, completely separate from every other profession. Many people believe in the “mad scientist” stereotype, thinking that only exceptionally gifted people can become scientists. In only a few months of exposure to science at college, it became clear to me that people who work in science are not gods at all, but authentic human beings.

When the gender stereotype and the scientist stereotype collide, society finds situations in which women have to prove themselves worthy, and, consciously or unconsciously, others might build assumptions about their abilities even with solid proof in front of them. It’s important to have a good understanding of what a nonbinary gender spectrum is. Sex, the biological determinant of our bodies, unless otherwise altered, does not equate with gender, and – as said by Valian – “[the genders] overlap.” A female-sex person can have a personality just as scientifically inclined as that of a male-sex person.

The Next Step: Fixing the Problem

Valian says in the final paragraph that gender stereotypes will be “eventually dispelled by education.” I believe the same. It is critical to the success of the feminist movement at large, and especially concerning the underrepresentation of women in science-related fields, to teach the general population why men and women are more alike than we are different.

Image source: link

Welcome to UR Blogs

Welcome to your student blog for the FYS-Women in Science!