Women Wasted

Virginia Valian probes the question of why aren’t more women in science through her essay Women at the Top in Science – And Elsewhere. She opens by explaining the misconception that there is not simply a lack of women at the top of the natural science departments, but also in fields commonly associated with women such as nursing and baking. This underrepresentation startled me as I had always thought women were only battling to make it in certain fields, but the workforce overall seems to be geared against women. Valian’s concepts of gender schemas and accumulation of advantage explicate what holds women down in the workforce.

Although Valian argues that differences in test scores do not provide a valid reason for why women are not at the top of their fields, I found the statistics rather interesting. I had heard the United States lagged behind certain countries in academic success on standardized tests, but I was surprised to find out that men and women in other countries were equally outperforming men and women in the United States. According to the international report of the 2002-2003 Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study, the Japanese girls scored 62 points higher than United States boys. There was a slight difference between men and women, but the most significant statistic was the national difference. Valian’s assertion that “the higher education system in the United States wastes women’s talent” struck me as hard to deny after reviewing these alarming statistics of differences in cross-gender and cross-national test scores. How could anyone say women are less talented than men with those facts? It concerns me that the education in America is not nurturing the abilities and potential of women like it should be. If women are capable and motivated to do the same work as men and excel past them, then what is holding them back?

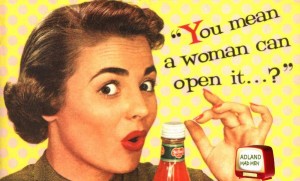

The obstacle holding women back, as Valian identified, is gender schemas that generalize being male or female by skewing “our perceptions and evaluations of men and women, causing us to overrate men and underrate women.” The picture in one’s head of what a woman is suppose to do with her life and what a man is suppose to do with his are very different, so when one is faced with a choice to decide who fits in what job, it is easy to judge based on those outdated and unrealistic pictures. Our previous bias is strong and difficult to look past even when the facts are presented because of motivated reasoning.

I am worried these inherent gender schemas will never go away. They aren’t the obvious wrong doings that are regulated by society. They are the unchecked thoughts in most minds when people think about work being done by a woman. They are the overpowering instincts that employers feels in their gut when evaluating the competence of job applicants or even current workers for a promotion. The effects are not necessarily visible at an individual level, but when women are completely underrepresented at the top of the science workforce in a country, the devastating reality is revealed.