I liked how Dr. Bezio commented on the incredibly complex nature of our systems, and how even when they are unequal you still might receive benefits from them. I was particularly interested in the discussion about the titanic. Whenever I would watch the movie, I struggled with the notion that women and children had to go first onto the lifeboats. This sort of infantilization of women is not a new concept, nor is the theory that they must be saved by men. As a feminist who believes in championing the equality of the sexes, I strongly disagree with the sexist rationale behind this systemic decision, however, if I was on the titanic, I think I’d be pretty grateful to get a spot on the lifeboat if it meant survival. Patriarchal norms and systems have been around for generations, and though it would be tough to not hop on a lifeboat in a titanic-type-situation, I think challenging these norms or pointing out the flawed logic that supports them whenever possible, is essential to progress.

Author Archives: Maeve Hall

2004 Democrat Ads

I really enjoyed this exercise. My favorite was the “Turned a Corner” ad because the charts are so funny and it reminded me of the how statistics can be deceiving. They were so sassy and iMovie quality I was laughing. I also thought the Tears of the Mother ad was very effective though it was a very different tone.

Blog post

I loved the nerve explanation of systems that was explained in Podcast 7 because it illustrated how even slight biases and issues in a system can have massive long term, and sometimes painful effects. Dr. Bezio’s point that systems management should not be done by one leader, or even by a small team, reminded me of what we’re discussing in my Stalin history class right now. (Not to sound like a Stalin apologist because he was horrible and made a lot of terrible and influential decisions in the USSR), but some scholars want to frame history by placing all of the state’s power and decision making on him, when in reality the USSR was essentially a giant bureaucratic state that could only function with lots of collaborative work. In the US, our tendency to idolize our leaders (something I’m guilty of, I have a picture of RBG on my wall) can become problematic because we fall into the trap of oversimplifying situations and missing the nuances of how systems really work.

I also liked her comparison of twisting your ankle while climbing a mountain and being allowed to adapt to new conditions to the unrealistic expectations we put on leaders to stick to their original stance even in new situations. Especially in light of the January 6th riots at the US Capital, the idea of term limits can way to transition systems without breaking them seems very relevant and important. Dr. Bezio points out that it’s hard to stop a system once it’s started running, which is called a homeostatic feedback loop. Updating a system can be difficult and slightly destabilizing, but there are ways to cope with that. The best ways to adapt and create positive system change, which Dr. Bezio says are long term thinking, not oversimplifying issues, and proactivity, all seem at odds with natural human instincts of reactivity. However, I’m interested in further exploring how we can encourage people to push back on our reactive instincts to solve larger problems like climate change. Understanding how systems really work means that we actually know what are the most effective areas to target for change, and that might not always be the most visible leader. In terms of social justice organizing, understanding that distinction can be vital for success.

Blog Post

Ad Post

I really enjoy this Progressive ad about not becoming your parents. I like this one because it shows us what we all fear, becoming our parents as we grow older. Even though we don’t usually want to become our parents, this ad makes our lizard brain connect Progressive with having the stability to own a home, something that a lot of millennials and Gen Z really want but do not necessarily have access to at the same level as their parents’ generation. Like Dr. Bezio discussed in her podcast, even if the ads don’t talk explicitly about the details of what they’re selling, they are probably trying to sell us the fantasy of what the product could do for us. In this case, it’s definitely meant to be a funny ad, and they say that Progressive can’t stop you from becoming your parents, but they can help insure new homeowners. Progressive is able to make fun of some “Boomer” stereotypes while also making millennials see themselves as potential homeowners one day, and progressive markets itself as an insurance agency that’s in touch with pop culture’s critique of the “Boomer” generation.

Blog Post

I liked the part in the reading that talked about how you might get data from the questions you ask, but it might not be answering the question you thought you were asking. In the example about what magazines people had in their homes, the researchers knew based on the circulation data for the magazines that people were lying and saying that they had the “higher brow” magazine. This showed that they weren’t actually measuring the kind of magazine people had in their homes, but instead their level of “snobbery” (18). We’ve been discussing this in my Social Science Inquiry class for Political Science and Jepson about how to collect this information, so it’s really interesting to discuss how data’s presentation can be manipulated. In the podcast, Dr. Bezio discussed how cheating numbers is a trick as old as time, and even if the numbers aren’t entirely fabricated, they are sometimes “beat into submission” to say what the author wants them to say.

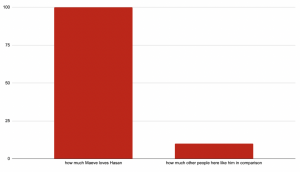

I definitely fall into the trap of accepting numbers at face value. Even from the first example in the reading about the specific income of Yale Class of ‘24 students, I made the assumption that if the number was specific, that also meant it must be very accurate. Learning this is not the case and that can be due to sampling errors and bad assumptions was a little embarrassing because it made me aware of how much I take numbers at their face value. As a humanities student, I am guilty of thinking that numbers aren’t lying to me because they feel so scientific and concrete. Honestly, looking at lots of numbers scares me and I prefer not to do it, but Dr. Bezio made a good point in her podcast that understanding numbers and statistics is an essential part of making good arguments in humanities fields. Who knows, maybe if I’m actually learning statistics in the context of things I care about it will be more understandable and interesting. After doing this reading I’m more aware of the common tricks for falsifying data so I can pick it out better in the future. My other major is Political Science, so understanding when someone is BS-ing numbers will likely be of critical importance going forward in my career! Below is a graph that I made as a joke for my application to meet Hasan Minhaj. It is a bad chart. I falsified all of my data and probably based it on untrue assumptions, my axis makes no sense and isn’t really labeled, but it was apparently pretty convincing to my audience because I achieved my goal of meeting him! I promise to never intentionally make a graph this trash again.

Podcast Response

In Flanigan’s article, she discusses how the idea of informed consent does not agree with the current pharmaceutical regulations because if a patient can refuse care based on their decision about their own well being, they also should be able to make their own decision about the drugs they use for their own well being. Her argument is that if the medical community widely accepts that patients know what’s best for themselves and can refuse certain treatments, it should also be widely accepted that patients know what’s best for themselves and don’t need the gatekeepers of pharmacists to keep them from the medicine they want or need. Personal cost benefit analyses are just happening on the black market for drugs anyway, such as Adderall, so why shouldn’t that happen legally? She also brings up the point about cosmetic surgery, where patients choose to take some medical risk for their desired outcome, and she questions if that risk is so different from prescription drugs.

I thought this had a really interesting connection to the podcast about the racist history of drug enforcement in the US and other failed programs like “Just Say No” and D.A.R.E. that aimed to teach and enforce limits on people’s drug use. Restrictive policies can be useful tools for public safety, and I don’t entirely agree with Flanigan’s argument that we shouldn’t have any gatekeeper for prescription medications. However, I think it’s fair to say that systemic racism has been a part of the drug enforcement process since it’s beginning, and it’s important to look closer for the purposeful or unintended consequences of that legacy in policies we make today.

implicit bias reaction

I took the implicit bias test about gender bias. I found myself really having to concentrate as they changed the sides around. My results said that I had “a weak automatic association between Me and Woman and a moderate automatic association between Not-me and Man. I was a little surprised that the connection between “me” and “woman” was not equally as associated as my connection between “not me” and “Man”. I think I spend a decent amount of time thinking about my female identity and women’s rights, but I guess that also plays into feeling particularly more separate from the male identity.

Blog Post 2

I took the implicit bias test about gender bias. I found myself really having to concentrate as they changed the sides around. My results said that I had “a weak automatic association between Me and Woman and a moderate automatic association between Not-me and Man. I was a little surprised that the connection between “me” and “woman” was not equally as associated as my connection between “not me” and “Man”. I think I spend a decent amount of time thinking about my female identity and women’s rights, but I guess that also plays into feeling particularly more separate from the male identity.

“Blindspot” by Mahzarin Banaji and Anthony Greenwald explores the hidden reasons for our biases. I found the section about the Innocence Project especially interesting because it provided a clear example of the real world effects of hidden biases. The reading mentioned how 250 people had been exonerated through the project, and 190 of those wrongful convictions were because of incorrect eyewitness accounts. They were able to go back and correct the cases by using DNA data, but the fact that 75% of wrongful convictions were based on false eyewitness accounts makes the importance of learning about availability and implicit bias all the more important. The reading described how we tend to trust people who have features that are similar to our own more than those who don’t. It was really easy for people to assign characteristics to images of strangers even simply based on their appearance and no other information. The authors argue that it’s harder for us to refrain from split second judgments than to not assign them in the first place.