I liked the part in the reading that talked about how you might get data from the questions you ask, but it might not be answering the question you thought you were asking. In the example about what magazines people had in their homes, the researchers knew based on the circulation data for the magazines that people were lying and saying that they had the “higher brow” magazine. This showed that they weren’t actually measuring the kind of magazine people had in their homes, but instead their level of “snobbery” (18). We’ve been discussing this in my Social Science Inquiry class for Political Science and Jepson about how to collect this information, so it’s really interesting to discuss how data’s presentation can be manipulated. In the podcast, Dr. Bezio discussed how cheating numbers is a trick as old as time, and even if the numbers aren’t entirely fabricated, they are sometimes “beat into submission” to say what the author wants them to say.

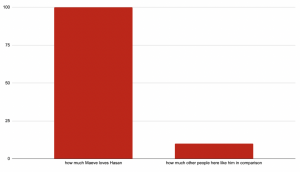

I definitely fall into the trap of accepting numbers at face value. Even from the first example in the reading about the specific income of Yale Class of ‘24 students, I made the assumption that if the number was specific, that also meant it must be very accurate. Learning this is not the case and that can be due to sampling errors and bad assumptions was a little embarrassing because it made me aware of how much I take numbers at their face value. As a humanities student, I am guilty of thinking that numbers aren’t lying to me because they feel so scientific and concrete. Honestly, looking at lots of numbers scares me and I prefer not to do it, but Dr. Bezio made a good point in her podcast that understanding numbers and statistics is an essential part of making good arguments in humanities fields. Who knows, maybe if I’m actually learning statistics in the context of things I care about it will be more understandable and interesting. After doing this reading I’m more aware of the common tricks for falsifying data so I can pick it out better in the future. My other major is Political Science, so understanding when someone is BS-ing numbers will likely be of critical importance going forward in my career! Below is a graph that I made as a joke for my application to meet Hasan Minhaj. It is a bad chart. I falsified all of my data and probably based it on untrue assumptions, my axis makes no sense and isn’t really labeled, but it was apparently pretty convincing to my audience because I achieved my goal of meeting him! I promise to never intentionally make a graph this trash again.

After reading your response, I feel that we, as a society, need to rethink educational pedagogy. We are often conditioned to do more accepting facts from credible sources, such as our professors, researchers in the field, or even students who graduate from elite institutions. Yet, we are not taught how to first critically analyze information. This has come to harm us if we think of this in relation to our social mind bugs.

I also felt embarrassed for being called out on always trusting the numbers because they feel like they must be true but I too feel better knowing I have the tools to not be taken advantage of by false numbers. Also I think any humanities major that has not taken this class would know that the data used to make your chart is biased (and also funny).

I find that I also don’t take the necessary time to really understand the numbers people use, even in humanities arguments, and just take them at face value and move on to the qualitative data. Similarly, my other major is sociology, which means that numbers and quanitiative data are a huge part of the research and scholarship! I agree that this lesson made spotting some of the common numbers manipulating tricks easier. The point about using question response data to measure something other than it is actually asking is super interesting, but now that I think about it, I feel like researchers do stuff like that a lot – but they typically disclose the true purpose of the study later on.