The 1922 “Rat Band” (photo: The Web, 1923)

The first marching band on campus was formed in 1917, as part of the Richmond College Battalion, an auxiliary unit of students receiving military training during World War I. In 1922, a group originally called the “Rat Band” (referring to a common nickname for first-year students), and later renamed the “Spider Band,” was formed to play at home football games.

The 1939 Spider Band, led by W.T. Sinclair (photo: The Web, 1940)

By the early 1930s, interest in the Spider Band had waned, so in 1938 the University hired William T. Sinclair, a public school music teacher, to revive the tradition. Sinclair left after four years, and direction of the band again fell to students, under the auspices of Omicron Delta Kappa. Complaints about the group’s modest size and musical ability were frequent.

(photo: The Collegian, Sept. 20, 1946)

As World War II veterans returned to campus, demand for an official marching band reached fever pitch. In 1946 the University hired Captain D.F. Joachim, the director of the John Marshall High School Band, to form a similar group at UR. Because too few students volunteered to play, the marching Spiders were often supplemented by musicians from local high schools and colleges. Joachim lasted only a year, and was replaced by his successor at John Marshall, Mark Troxell. Troxell’s “reawakening of school spirit” was so greatly appreciated that Richmond College dedicated its 1949 yearbook to him.

The UR Band took another step forward in 1950, when female students were finally allowed to participate. At first, the band wanted women only as majorettes, which were needed in order to succeed at state competitions. The Westhampton faculty vetoed this request, on the grounds that majorettes were “not in keeping with the ideals of the school.” Women were invited to join the band as musicians, but only during the concert season, when they did not march.

Tom Savage, the Spider Band’s 7-foot-tall drum major (photo: The Collegian, Nov. 5, 1954)

For decades, the Spider Band rehearsed in the YMCA Building, a structure that stood behind Residence Hall No. 1 (formerly Jeter Hall). In 1951 they were given exclusive use of that building. Chronically undersized and underfunded, the bands of the 1950s were nonetheless in demand. In addition to playing at home football games and pep rallies, they marched in parades (including Homecoming, the Tobacco Festival, and Thalhimer’s Toy Parade), and performed at the Interfraternity Council Christmas party for local children, as well as at nearby colleges and schools. They also fared well in music competitions across the Commonwealth. Band members earned just half an academic credit for considerable effort: besides their numerous performances, they rehearsed and drilled three hours per week.

Mark Troxell left UR in 1957 to oversee music in the Henrico County public school system. Robert Barker, a Yale-educated clarinetist and Air Force veteran, was Troxell’s replacement. Barker faced a perennial challenge: while the University’s concert band thrived, few of its members could participate in time-consuming marching drills. Throughout most of the 1960s, the R.O.T.C band, already expert marchers, filled in for the Spider Band.

The 1968 R.O.T.C. Battalion Band (photo: The Web)

In 1968 the Richmond College Student Government Association commissioned a study to explore the disconnect between the University’s desire to have a marching band and the students’ reluctance to join one. Their report included recommendations by music professor James Erb. Erb advocated for the creation of band scholarships, a standard practice at schools with successful marching band programs. His advice was not followed.

The following fall, newly hired Band Director James Larkin announced an ambitious plan to organize a 50-person marching band to perform precision drills and play “popular show tunes and school songs.” Larkin’s band, while slow to get off the ground, eventually consisted of some 60 members, including women, though with minimal funding and no scholarships. The band supported the UR football team at the 1971 Tangerine Bowl, marched at the 1973 Edison Pageant of Light in Ft. Myers, Florida, and led a parade at Walt Disney World. The University no longer banned majorettes, but it refused to pay for their uniforms.

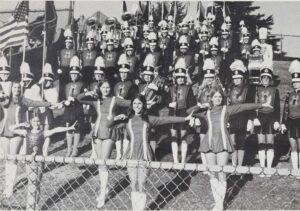

The 1974 Spider Band marched with female musicians, majorettes, and a Confederate flag (photo: The Web)

During Larkin’s tenure, some of the Spider Band’s traditions increasingly conflicted with the evolving values of the campus and the country. In 1971 the Richmond College Senate asked the band to limit their playing of “Dixie,” because, according to The Collegian, the song “could be detrimental to some of the University’s aims, such as the recruitment of blacks.” In an acrimonious letter to The Collegian, Larkin argued that “Dixie” was a “catchy, happy tune with not a racist word in its lyrics.” Nonetheless, he agreed to remove the song — temporarily — from the repertoire. Around the same time, Provost Robert F. Smart requested that the band stop marching with a Confederate flag, although the practice continued for a few more years.

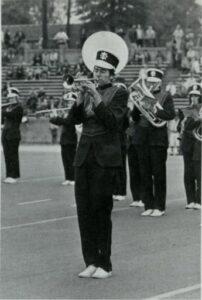

The UR marching band in one of its final seasons (The Web, 1977)

In 1975 David Graves was hired as Larkin’s replacement, but with only a dozen musicians, none of them percussionists, there was no marching that year. Graves reiterated the need for band scholarships, which finally materialized in 1976: $500 scholarships (about $2,300 in 2024 dollars) were offered to twelve students, prompting Graves to forecast “the best season in several years.” Unfortunately, the band’s numbers remained small. Graves, who also taught courses in music education, explained that both he and the student musicians were overextended, and without significantly more funding, the University would never have a first-class marching band. Observing that “we can’t outdo West Virginia Tech,” President E. Bruce Heilman admitted that a mediocre band was worse than no band at all. In 1979, acting on a recommendation by the Department of Music, the Board of Trustees voted to defund the marching band. Its remnants regrouped as a pep band playing on the sidelines, and the majorettes rebranded as a “spirit squad.”

Throughout its roughly sixty-year history, the UR marching band was caught between the dream of “Seventy-six Trombones” and the reality of its cost in both time and money. The group’s demise was rooted in a fundamental disagreement: the Music Department felt that the band should be funded by the Athletic Department, since its repertoire prioritized entertainment over its members’ musical development, and most of its expenses stemmed from performing at sporting events. The Athletic Department countered that a musical group should be the responsibility of the Music Department, regardless of its function. In the end, no one wanted the UR marching band enough to save it.

The ghost of the marching Spiders recently resurfaced in the form of a band uniform discovered in a closet.