The story I listened to was about a young boy, David Lepelstat, who almost drowned in his family’s pool. Fortunately, he was saved by his uncle’s partner at the time, a man named Michael. The story is about redefining family and appreciating people for who they are, not the labels attached to them. The man, Michael, wasn’t related to David by blood, so David never really considered him a part of the family. However, once David saw the lengths Michael went to to help him, even saving his life, he realized that family didn’t necessarily have to be all about blood. I think this story is really touching because it shows how arbitrary terms like “family” can be. Just one instance can change completely how we think about others. It’s so easy for titles and relationship defining terms to change as we grow as people. To me, this speaks to the idea that no matter how something might feel in the moment, there isn’t anything in life that can’t change over time. This can be a good thing or a bad thing depending on how you look at it, but to me it’s reassuring. Time can fix relationships, heal emotional wounds, and make Michael, or whoever Michael represents, a part of the family.

Category: Will S Page 2 of 3

Chapters 4-10 of Persepolis were even more interesting to read than the first three. Once again, I was captivated by the narration. The author’s portrayal of childhood thoughts and emotions is basically flawless. It makes the story of the young girl growing up in this tumultuous time really hard hitting. I also love the growth that we can see the narrator undergoing over the course of the story. It’s clear that she is learning more about her country and beginning to form her own morals. It’s a beautiful journey that I feel privileged to be privy to. The matter of fact narration, a staple of any conversation with a child, also continues to make Persepolis a truly heartbreaking read.

One thing I noticed while reading the first three chapters of Persepolis was the way Marjane Satrapi embodied the perspective of her ten year old self to deliver the story. The childlike innocence of the narrator comes across in the way she speaks and the conclusions she draws about her life and the things happening around her. Because the narrator isn’t old enough to grasp the full scale of the events in her life, she describes and reacts to events in a simplified way. This builds a sense of dramatic irony into the narrative. Every time the narrator stumbles upon something really emotional or profound, she says it in a very stark, unembellished way because she doesn’t know the gravity of what she is saying or thinking about. However, we as readers do understand how powerful, thought provoking, and heartbreaking some of these statements are. This makes those moments even more powerful because we feel not only the emotions and implications of the actual events of the story, but also the emotions and implications that come with the narrator not understanding situation fully. We are saddened by the events of the story, cheered by the narrator’s childlike happy-go-lucky demeanor, before being saddened again by the realization that the narrator can’t comprehend the tragic events surrounding her. It’s this second sadness, the tearing down of our emotional barriers so soon after they had been built back up, that really lends weight and impact to Marjane Satrapi’s storytelling.

One question I have about our Midterm Portfolio essay is how much summary we should have. For prompt two, should we recount a summary of the whole story we are discussing, or should we just talk about certain points that are the most important to our essay?

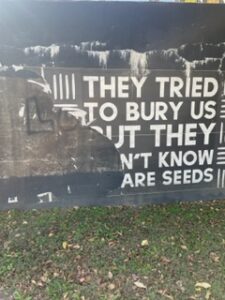

This picture is of a mural that was painted near the burial site we visited. It was located close to the street, along the wall where the signs displaying the numbers you could call to hear about Gabriel were located. The mural seems to be sending an inspiring message about rising up from hate and oppression, but the thing that stood out to me wasn’t the message of the mural, but the message sent by the fact that it was defaced. The disregard and irreverence with which this mural was treated is really sad to me. And this same treatment is repeated throughout the site, with trash and litter scattered everywhere and telephone poles and lights standing right in the middle of the burial grounds. There seems to be a general lack of care given to the site. I know that there are ongoing efforts to restore and preserve the burial ground, but they seem to have an uphill battle ahead of them. I can only hope that in the future there are more resources given to those who want to protect and preserve such an important historical site, and those resources allow this important part of Richmond’s history the respect and reverence it deserves.

The idea of the poll tax and it’s origins really stood out to me as an interesting topic when I was reading Campbell’s book and the initial source I chose, Managing White Supremacy, so I decided to look into that more for my research. The library’s OneSearch filters were really helpful in leading me to a peer-reviewed article, but I had a little more trouble finding a second source. However, the databases that Nick, the librarian, showed us pointed me in the right direction. I was able to find two sources that I found interesting with relatively little difficulty, and I can’t help but be thankful for the great resources available at and through the library that made the process so smooth.

When reading Richmond’s Unhealed History, one of the parts of the book I was most interested by was the portion of chapter seven where Campbell broke down the ways in which Richmond’s white upper class ensured that they stayed in power through the repression of black voters. The callousness with which these politicians treated segregation and discrimination really shocked me. The source I chose to research is J Douglas Smith’s 2002 book Managing White Supremacy. This book was cited by Campbell multiple times as a resource detailing the discriminatory tactics used by white politicians against black people in Virginia.

I expected to have some difficulty finding a good source to use for my annotated bibliography, but I was happily surprised to learn that the first source I looked into, Managing White Supremacy, was in the stacks of Boatwright Library. It did take me a couple minutes to figure out the shelving system in the Circulating Books area, but once I did, I found what I was looking for in no time, and was able to check it out at the front desk. I’m grateful that UR has such great resources available for students, but I assume that research in the future won’t always be that easy.

When reading chapters 7 and 8 of Richmond’s Unhealed History, one of the things that really stood out to me was the ways in which racial segregation was preserved in Virginia through legal loopholes and gerrymandering. It shocked me that even after segregated public facilities and schools were banned, Virginian politicians went to incredible lengths to ensure that power remained in the hands of white people. Using the process of annexation in order to ensure a white majority voting population in Richmond, and other similar policies all intended to uphold the statue quo of racial segregation, shows just how deeply ingrained racism is in our society. I was saddened by the accounts of important black neighborhoods being demolished in order to construct massive super highways and I can’t believe that it was so easy for Virginia law makers to casually displace thousands and thousands of families with next to no support for them. I hope that there have been, and are still, efforts made to preserve and restore these historic neighborhoods to ensure that this essential piece of Richmond’s history isn’t lost forever.

I found this week’s reading, chapters 4-6, to be really interesting, mostly because of the narrative structure Campbell employs throughout these chapters. Campbell made use of many primary sources in the first few chapters of the book, but in these chapters he doubles down on the emphasis of primary sources, particularly stories told by people in and around Richmond. Full pages in these chapters are taken up by first-hand accounts by figures such as Fredrick Douglass, Eyre Crowe, Anthony Burns, and Charles Dickens. This structural choice seems to indicate that Campbell feels that the information he is trying to impart on his readers is most impactful when coming from the people who experienced it first hand, an opinion I agree with. The stories and observations displayed in these chapters are truly impactful because they depart from mere summary of historical events, and instead present the readers with the real, gritty details surrounding the horrors of slavery in Richmond.

Another detail that Campbell mentioned that I thought was really surprising was the fact that so much of Richmond’s history was unknown until recently. The fact that the domestic slave trade played such a big part in the city’s economy, yet was almost completely concealed from the public was shocking to me. It reminded me of what Ana had brought up in class on Thursday (9/28), when she spoke about how information regarding the mistreatment of Native Americans had been blocked by her high school. I think that it’s essential to confront our history as a nation, the horrific parts especially, in order to rectify the wrongs of the past and grow as individuals and as a collective, and the fact that parts of America are trying there best to prevent such self-reflection is both disappointing and frightening.

The story of the founding of Virginia is a truly painful one to think about. The story, as detailed by the first two chapters of Benjamin Campbell’s Richmond’s Unhealed History, is fraught with colonial greed, abject racism, and atrocities committed against indigenous people. Although Spanish settlers had explored the area in prior years, the first true settlement in Virginia came by way of a British expedition. And from the start, conflicts with Native Americans began to become a major part of life for the settlers. Peaceful relations between the English and chief Powhatan soon fell apart as the English settlers who founded Jamestown were attacked by the native people. A lack of respect for the rights of the indigenous people doomed the settlers to hostile raids and attacks throughout the early years of the Virginia colony.

The relationship between the English and the Native Americans didn’t improve with the multiple changes of governor that the colony underwent. In fact, it seemed they got even worse, with a horrifically matter-of-fact account by George Percy detailing the atrocities he committed against the Paspahegh tribe under the command of Lord De La Warr being particularly chilling. Of course, not all the settlers or Native Americans held hatred toward the other, but the terrifying actions of those who did overshadow those settlers that tried to treat the indigenous people with respect, and the indigenous people that attempted the same.

As a result of English settlement, Native American numbers dropped from close to twenty thousand to two or three thousand in around fifty years. The English-Powhatan war, and even the relations between the two groups prior, is a brutal example of the horrific treatment of Native Americans by early English settlers and it is the most painful, yet also most important thing to consider when trying to understand the foundation of Virginia.