History

By: Colby Alvino

What is Fiat Money?

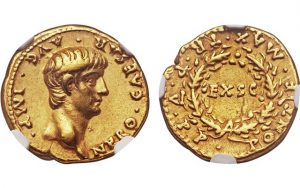

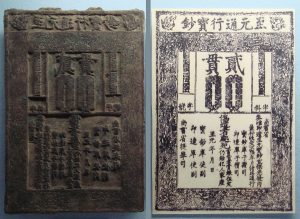

Before we are able to discuss the history of fiat money, we first must address what fiat money is. Fiat, in Latin, means “let it be done.” Fiat money refers to a medium of exchange that is not a commercial commodity, a consumer, or a producer good. It is also not a title to any sort of paper money, such as irredeemable paper money (Hoppe 1994). There is constant confusion about the difference between fiat money and commodity money, but the latter signifies something quite different. A commodity is a medium of exchange that is either a commercial material or product, or a title to paper money, so what the two terms are in reference to are actually quite opposite from one another.

Therefore, unlike gold, which we can think of as a scarce mineral with a rare supply and a great demand for it, thus giving it substantial value, fiat money has no intrinsic value but is declared legal tender, or banknotes accepted in exchange for payment of a debt, by the government. However, it is not supported by a physical commodity.

The Origin of Fiat Money, New England 1620-1789

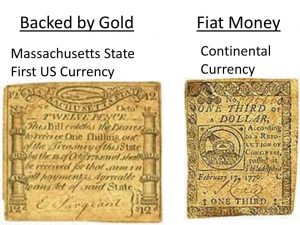

In 1692, the General Court ordered that “all Bills of publick creditt, issued forth by order of ye Generall Court of ye late Colony of ye Massachusetts Bay, shall pass current within this Province in all payments equivalent to money and in all publick payments at 5 per cent advance” in order to facilitate the paying of debt to soldiers after failed military expedition through the dignity of fiat money (Massachusetts Archives). As financiers attempted time after time to ease their way out of economic turmoil that legislators had laid out for them, they began to welcome this idea of fiat money, as it was perhaps their only hope of relieving their financial burdens. And alleviating their burdens only meant tightening the binds of cheaper fiat money, for only those who possessed it, before it became a normality, knew of its worth and value.

The people of Massachusetts later attempted to rejuvenate fiat money so that the inconvertible paper money could gain popularity among the people of New England. Massachusetts tried to regulate the fluctuating currencies by producing an equity bill to facilitate matters, which became law in the year 1742 (Acts of Massachusetts). This bill allowed the colonies to issue paper currency as legal tender to pay for public debts. By attempting to reintroduce fiat money to society, they were subconsciously launching province bills, as they had a purchasing power comparable to coined sterling silver. While this was happening in the 1740s, there were £120,000 of silver bills in circulation. In contrast, gold and silver did not circulate much because they were sent to England when they entered the world of commerce, and, in turn, the realm of fluctuating currency temporarily destroyed commerce. This is because port ships were sitting around untouched due to the sudden changes in the economy as a result of this introduction of fiat money. Ship building was the chief industry of New England, so as inflation rose, business fell.

The colonies’ ability to produce fiat money was destroyed by the British Currency Acts, therefore causing that continental currency to be produced during the war. The entire system of fiat money collapsed in 1778, for its value was depreciated constantly throughout continental times (McLeod 1898). On December 16th in 1780, Jonathan Amory, a merchant by trade from Boston, said, “Everybody asks silver or gold or paper, as they please, paper having been for a considerable time at 75 percent; goods bring three for one. … A good proportion of the money I took for debts was not worth one-third, and before I had a chance to lay it out, perhaps not one-sixth of what I had taken it for” (McLeod 1898).

Fiat Money’s Role in American History, The Revolutionary War

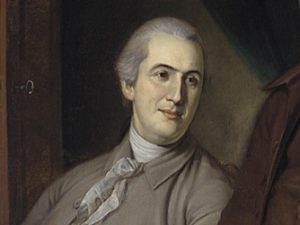

When the Revolutionary War broke out in the year 1775, Gouverneur Morris (1752-1816), a Founding Father of the United States and member of the committee that wrote the final draft of the Constitution, decided almost immediately to persuade the Philadelphia Congress to issue paper forms of fiat money in order to create free revenue and finance the war efforts (Rothbard 2002). The Philadelphia Congress, otherwise known as the Continental Congress, comprised a group of delegates who later went on to serve as the United States’ governing body during the war. This group was intrigued with Morris’ vision of introducing fiat money, as there were very little specie in the country to begin with, and Morris pledged to let taxes slowly allow fiat money to retire, which would allow the paper money to cause inflation. Specie simply refers to money in the form of coins rather than bank notes.

However, the Philadelphia Congress quickly forgot about the plan to allow it to retire, as they were so mesmerized with the idea of making costless money. By the very beginning of issuing the paper money, it immediately became clear that more money would be needed, more specifically, about an additional $1 million, as its concept received a lot of attention from citizens. After being welcomed by the public for an entire year, an additional $6 million of paper money had been issued, and it continued to spiral over the next several years. Most people believed that this was the reason behind the depreciation of fiat money: Because there was too much demand for paper money. Others believe continental currency depreciated because people lost confidence in the idea or because it was not backed by tangible assets.

Abner “Woody” Linwood Holton III, a professor of history at the University of South Carolina, surfaced in a collection of essays published by Columbia University Press in 2018 titled “American Capitalism: New Histories.” In the essay, “The Capitalist Constitution,” Holton writes that “during the recession that followed the Revolutionary War, farmers frequently asked their representatives for relief from their obligations to the tax man and their debts to local stores,” but that “state assemblymen had no choice but to accede to their constituents’ demands for tax and debt relief ” (Holton 2018). In response, the Constitution of the United States worked so that its new national government would not take on a new way to relieve its issues concerning both taxes and debt. A transcription of the Constitution, in turn, does read under Article I Section 8 that “The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States; To borrow Money on the credit of the United States…” (U.S. Constitution). The Constitution did indeed pay off the debt resulting from the Revolutionary War by imposing sufficient taxes, and sequentially regulated the relationships between creditors and debtors. Similarly, with the Consolidation Act of 1781, Massachusetts printed new bills, and the value was determined by the judicial court of Massachusetts. The act stated that the debt was to be consolidated, and that currency would not pass at its face value (Brooke 1992). When the printing of new bills occurred, the court banished the bills that came from private transactions, as these proceedings were in no way able to be trusted. The banishing resulted in making matters even more difficult for the colonial people.

Concluding Thoughts

The history of fiat money shows that its initial development and practices throughout the years were anything but perfect. The United States made several attempts in using the paper money. However, as history shows, it typically ended in devaluation and eventual collapse of the currencies. Some even argue today that our current U.S. dollar bills are quite similar to the paper money issued during the Revolutionary War. Similar to Morris’ pledge to let taxes slowly allow fiat money to retire, allowing paper money to bring about inflation, fiat money today risks losing value and worth due to hyperinflation, which is extremely rapid inflation. This frightens citizens because most modern currencies to date are in fact fiat currencies, and some are even quite stable. And, it is not certain that fiat money will ever be associated with instability.

References

- Hoppe, Hans-Hermann. “How is fiat money possible?—or, the devolution of money and credit.” The Review of Austrian Economics 7, no. 2 (1994): 49-74.

- Massachusetts Archives — “Pecuniary,” Vol. i

- Acts of Massachusetts

- McLeod, Frank Fenwigk. “The History of Fiat Money and Currency Inflation in New England from I620 to I789.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 12, no. 2 (1898): 57-77.

- Rothbard, Murray Newton. History of Money and Banking in the United States: The Colonial Era to World War II, A. Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2002.

- Holton, Woody. “The Capitalist Constitution.” In American Capitalism: New Histories. Columbia University Press, 2018.

- U.S. Const. art. I, § 8.

- Brooke, John. “Conventions, Regulation, and Antifederalism.” In The Heart of the Commonwealth: Society and Political Culture in Worcester County, Massachusetts, 1713-1861. 1992.