Mary Magdalene: Visionary or Drama Queen?

Introduction

In the canonical Biblical works, a woman is elected by God to report to the disciples that Jesus has fled his tomb. A contemporary reader may wonder; does the ancient reputation of “unreliable women” serve to bolster the authenticity of their discovery or to detract from it? Why would the early church work so hard to produce a story with credibility only to end it with an account from the perspective of a person who can’t be trusted? Would that not give it even more credibility 2000 years later? John 20:18 reads “Mary Magdalene went to the disciples with the news: ‘I have seen the Lord!’ And she told them that he had said these things to her.” It is astonishingly brief, and it does not convey much about the encounter or the reception by the disciples. The Gospel of this woman, Mary Magdalene, is a mystery to locate chronologically in the canon. Karen L. King, an established scholar in the subject of Mary, fits its events into either Romans 7 or John 20. What remains of this Gospel is short, but it recounts a risen Savior’s spiritual insights as well as a depiction of Mary’s immediate encounter with the disciples. We will focus more on this encounter and the political dynamics at play in their discussion. Their first reaction is something along the lines of “this is quite weird for Jesus to say.” Peter and Andrew then question the reliability of Mary’s teachings. Mary’s vision certainly maintains a stark thematic contrast with other scripture. It maintains an obvious chronological alignment with the canonical gospels, but their reaction begs the question; could it be that her femininity played a part in either establishing or eroding the credibility of the Gospel of Mary in the early churches?

Drama Queen

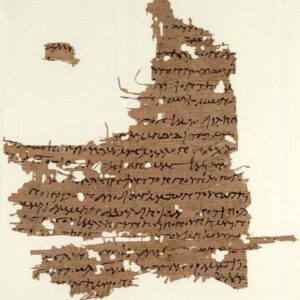

There is clearly some drama occurring between Mary and the disciples. Would the form of the scripts detract from this narrative? As it turns out, there are differences between the various forms of Mary’s document relating to this department. While two papyrus fragments of the text were discovered in Greek in the 20th century, the biggest compilation of the Gospel of Mary is the Berlin/Akhimim codex written in the Sahidic dialect of Coptic (Tuckett 80) (Journal for the Study of the New Testament 138). While it is disputed amongst the community, religious scholar Esther de Boer maintains that the original manuscript of this document must have been written throughout 75AD to 125AD and the Berlin Codex in the fourth century AD (de Boer). What is important about these three documents is that the Coptic translations add a “popular girl” element to Mary’s statement. According to the Coptic fragments, Mary says she had a teaching that was “hidden” from them (King 84). In this time and community, receiving a vision from the Lord implied that one had a capacity for mental clarity far above others. Therefore, Mary’s recounting of the vision is a triumph over the other disciples before it even begins. In this time period, such an implication is an affront to the norms established by the Roman world. The savior exclaiming “how wonderful you are for not wavering at seeing me” in her account simply rubs salt into the wound (GMary 7:3). From these phrases that Mary uses in her testimony, she is immediately presenting distinction whether or not it was intentional.

Visionary of the Disciples

In this, Peter may see her taking the side of the “Powers” (the side against the good guys) which is defined by their “divisive rivalry” (King 85). Peter immediately retorts with an obvious emphasis on her sexuality. He asks the other disciples “did he really speak with a woman in private, without our knowledge?” (Meyer 40). In questioning her validity through the lens of sexual boundaries, he feeds into the concepts that she just described. By using the word “a” as the indefinite article, he is assuming that no woman is fit to take this role. It is challenging to figure out who wrote this Gospel in its three fragments, but the battle lines between Mary and Peter are clear for the audience. While Mary emphasizes multiple times that she is chosen, Peter offers a similar contribution to division among the disciples. It is a conflict that is conveniently resolved by the scribes of all three fragments. Levi states “we should be ashamed and put on perfect humanity” (Meyer 41). Instead of serving the Powers by insulting Peter, he disperses his sin onto their entire group. It could be a political act to maintain the church’s solidarity, or it could be Levi adhering to the advice against division in Mary’s vision. After all, his phrase “perfect humanity” would fill similar shoes of the “soul ascension” that she just described in her vision. Levi’s role as the conflict solver is a sign that the author of the text prefers the alliance of Mary and Levi instead of Peter and Andrew. The earliest church, this band of disciples, seems to so far approve of Mary’s position as a visionary.

Lost in Translation

Pause for a moment. Did everyone walk off without a qualm and preach the Word just as Levi instructs them to? There is no dialogue after Levi exclaims “let’s preach the good news.” Once again, the translations of these documents will give further insight into the answer to this question. The Greek version maintains that “Levi left and began to announce the good news” while the Coptic version switches “Levi’ with “they” (GMary 9:10). While the authors may have approved of Mary’s vision, it becomes clear that the rift in the disciples persists in this Greek translation. It is thereby necessary to employ scholarly strategies to determine which edition should be considered closer to the original document. Bart Ehrman advises us to examine different criteria for establishing a text; this includes “age of the manuscripts” and “the more difficult reading” (Ehrman 29). As previously mentioned, the age of the Berlin Codex dates back to the fourth century AD while the Greek fragments date back to the early third century. In this department, the Greek fragments are assumed to be closer to the original manuscript. As for the more difficult reading, Ehrman’s qualification is “dubious theological views” (Ehrman 30). This aligns with the Greek translation’s tendency to elevate Mary’s status and exclude Peter and Andrew from the conflict resolution. Keep in mind that Mary’s femininity is Peter’s primary concern rather than her vision. The lack of resolution undoubtedly places almost all of the disciples in the position of rejecting Mary’s vision. Nobody follows Levi. The earliest church as we know it saw this femininity as a corrupting quality of her Gospel.

Who Cares?

If this first church placed the importance of her femininity above the importance of her teachings, there must be some reason for us to still be talking about it. If the document were truly irrelevant to the teachings of all early churches, it would never have been remembered, written, or reproduced. So who did care about the Gospel of Mary? The Galasian Decree of AD 492 banned it even for devotional reading! The Roman Catholics excluded it too (Mathewes-Green 5)!

Is the Gospel of Mary for the “Odd” Christians?

Our answer must lie in one of the “odd” sects of Christianity. Esther de Boer claims “the decisive characteristic of Gnosticism is the radical distinction between the true God and the creator God of Genesis” (de Boer). This is representative of her belief that Gnosticism is more of a category for the people interested in later writings for us to better understand them (Decock). However, Christopher Tuckett would argue that their identity is affected by their secret and ongoing revelations from God (Tuckett 370). In other words, the Gnostics can be described as unconventional and unorthodox. They pursued many unusual books to discover more about dualism and visionaries, and they would come into constant theological conflict with their counterparts. Would it be such a stretch for them to adopt such an obscure teaching like the Gospel of Mary?

Projection by the Gnostics

De Boer sees Peter as Jesus’ right-hand-man throughout the Gospels of Matthew and Luke while she claims Mary Magdalene as the possible identity of the beloved disciple and right-hand-woman in Mark and John (De Boer 195). The Gospel of Mary acts as an answer to this hypothesis since the rivalry is fully brought into the light. Through this frame, their rivalry can be seen as the result of one factor; her femininity. This makes her an unconventional rival as well, and she cannot use identical tactics to Peter’s. In fact, her role in the end is to cry while Levi retorts.

Where the Gnostics may have seen their place in this rivalry is in their obsession with the manner of teachings rather than the content. Mary received the revelation in secret, yet the orthodoxy prefers public teachings. Therefore, the Gospel of Mary functions as a representational story as well as a testimony. The representations of male and female are present, but Gnostics may have been more interested in these representations of themselves postured against the orthodoxy (Tuckett 370). The story functions for both purposes. The orthodoxy characterized as Peter would be hot-tempered, and this would serve well in a Gnostic agenda. In this case, the Gnostics would be far less concerned with Mary’s femininity as an obstacle to their adoption of the Gospel of Mary.

Lovers of Vision, Mind, and Dualism

Christopher Tuckett’s definition of Gnostics as adherents of secret visions is an obvious match for confirming this Gospel as part of their domain. It is then necessary to test the Gospel again by using de Boer’s definition. Can this dualism of lower and higher Gods be found in either the feminine or masculine terms used to describe the Powers or the Soul? In her analysis of the ancient Greek, she found that “three of the four powers of passion are feminine” while the goal of the soul’s ascent is “again described with female imagery” (De Boer 9). The masculine and feminine terms inhabit both sides of the battle. It treats them on somewhat of a level playing field, and in doing so muddles the proper requirement of dualism.

The vision in the Gospel of Mary is full of spiritual and mindful teachings, and this is in line with Gnosticism’s emphasis on the inner spirit of humanity (Tuckett). The Gospel of Mary attests to Mary Magdalene’s clarity of mind, and this is the given reason for why she is chosen to receive the vision. This is certainly in line with both Silke Petersen and de Boer’s presumptions of Gnostic beliefs (de Boer 9). So if a woman’s mind is up to the Savior’s standards, is she accepted as an equal? Petersen claims that the mind is at the root of women’s Gnostic Christian discipleship, but that “they could only join the community on the condition that they put aside their feminine nature and bec(a)me male” (de Boer 9). This is also a task of the mind, but it is a significant theological difference from the first church that we examined. They maintain a significant degree of acceptance and even enthusiasm for Mary Magdalene’s vision. It seems like such an inclusive community if the female member chooses to simply…banish her differences.

Conclusion

The Gnostics appear to be on board with everyone else’s presumptions about femininity within the church. Where they split off (as they always do) is in the option given to women to leave their femininity behind. It is difficult to determine if this is an embrace of the feminine. However, after seeing the many ways that the Gospel of Mary puzzle piece fits into the Gnostic puzzle, it is safe to assume that her femininity is not an establishment of credibility. Instead, the quality of her mind was the element that dragged Gnostic thought throughout the Gospel.

The first few centuries after Anno Domini were rife with the exclusion of women. They could not even be considered Roman citizens. In our greatest translation of the Gospel of Mary, she is seen as rejected by her disciples for her vision. This is not a result of the content of her message but rather the inherent rivalry between the “masculine Peter” and “feminine Mary Magdalene.” The only plausible early churches that could have taken up her message would have been the Gnostics, a group devoted far more towards the “mind” than inequality. It is likely that various Gnostic sects rejected the Gospel of Mary on the basis of duality, but others would accept it as a testament to the Savior’s appreciation for the clarity of mind. In any case, it is difficult to see how Mary Magdalene’s femininity added to the credibility of her Gospel in the eyes of the early churches.

Sources and Works Cited

Karen L. King, The Gospel of Mary of Magdala

Christopher Tuckett, The Gospel of Mary p. 80

Journal for the Study of the New Testament 27 (2005) p. 138-148

Meyer, Marvin. The Gnostic Gospels of Jesus

Mathewes-Green, Frederica. The Lost Gospel of Mary.

Ehrman, Bart, The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings.

De Boer, Esther, The Gospel of Mary: Beyond a Gnostic and a Biblical Mary Magdalene.

De Boer, Esther. The Gospel of Mary: Listening to the Beloved Disciple

Decock, Paul B. “The Gospel of Mary : Beyond a Gnostic and a Biblical Mary Magdalene. (JSNT Supplement Series 260), Esther de Boer.”

Tuckett, C. (2007). The Gospel of Mary. The Expository Times, 118(8), 365-371. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014524607077865