The Babylonian Exile was a period between 597 and 539 BCE in which the Babylonian Empire conquered ancient Israel, destroyed the Jewish temple, and forced much of the Jewish population into captivity within Babylon. As you can imagine, this traumatic event was a total disaster for the Jewish religion and culture of the time. In this blog, we will dive into how the Babylonian Exile fundamentally transformed Jewish identity and practices in lasting ways that were still felt during Jesus’s time over 500 years later.

Pre-Exile: Temple-Centric Judaism

(Artist rendering of how the First Temple may have looked: https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-first-temple-solomon-s-temple)

(Artist rendering of how the First Temple may have looked: https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-first-temple-solomon-s-temple)

Before the Babylonians seized control, Judaism centered around the temple priests and daily animal sacrifices performed at the Jewish temple in Jerusalem. The kings from the line of David and priests from the line of Zadok were in control of essentially all of the worship and ritual aspects through the period of the First Temple. And because the temple served as a powerful symbol of God’s presence with the Jewish people, the heart of religious life, and the place where heaven and earth met together, the temple priests served as a pseudo-elite group in charge of offerings, festivals, and all official cultic business. However, this temple-centric religious structure was devastated when the Babylonians arrived on the scene.

The Destruction of the Babylonian Conquest

The impact of the Babylonian conquest on Jewish religious infrastructure and national morale can hardly be overstated. In 597 BCE, when Babylon attacked Jerusalem, they sacked the temple, slaughtered many of the inhabitants, and forced the leading Jewish classes like royalty, priests, scribes, and other elites into exile in Babylon. According to Elelwani Farisani, a scholar at the University of South Africa, for those taken into captivity, the diaspora displaced 10,000 Jews, only about 5–10% of the total population during 586 B.C.E., from their Judean homeland, but the true impact was in what social classes were displaced. The main Jewish population was left without the royal family, military leaders, religious leaders, and other educated or skilled craftspeople, thus minimalizing any potential rebellion leaders. Those left were essentially just farmers with little to their names.

With the temple completely destroyed, the Ark of the Covenant and its cherished relics disappearing (probably stolen as Babylonian soldiers looted the temple), and the line of David dethroned, the heart of the Jewish nation was ripped out. The entire previous power structure was gone. Even while under Persian occupation after 539 BCE, when some political and religious autonomy was restored, the psychological scar was deep. This was an incredibly disorienting existential crisis for the Jewish religion and the Jewish population.

Exile decentralizes Judaism’s power structures.

Faced with this catastrophic dispersion, Judaism was forced to radically reinvent itself with the advent of new foundations. With the central temple gone, along with the hierarchy of priestly leadership that once governed worship for the nation, Judaism was forced to localize. Regional villages, diaspora communities, and those who remained in Jerusalem had to improvise to keep the Jewish faith alive.

The necessity of worship birthed innovation. Local synagogues that were led by rabbis and scribes popped up across Judea and wherever refugees settled, becoming gathering places and unconventional houses of worship. Marc Brettler, a biblical scholar at Duke, emphasizes how synagogues with rabbis leading prayer and study essentially became mini temples. He explains that Ezekiel preaches to the Jews that they do not need an actual building to worship God as he dwells within the Jewish community, not just a physical place like the Temple. Therefore, synagogues were able to serve as the main institution of Jewish life, in which the religious rituals could thrive.

Destroying the temple’s structure of authority forced Judaism to decentralize to survive. Jewish identity and practice were no longer associated with one specific location, but instead with many. At the center of community spiritual life, local rabbis with their small village synagogues completely replaced the importance of the High Priest in Jerusalem. A religion once led by priestly sacrifices evolved into the many local customs and worship using the study of the Torah under rabbinic leadership. This new “portability” of Judaism enabled the Jewish identity and faith to thrive across the diaspora even after the loss of national identity and their forced immigration away from the promised land.

Reimagining the Covenant Relationship

Losing the temple also shook Jewish theology to its core. With pre-exilic thinking, the way the world worked was both extremely neat and easy to comprehend: obey God’s laws and be blessed; violate them and be cursed. Bad things like conquest and exile were punishments from God for the sins of the people and king, while prosperity showed divine favor. But the temple’s destruction and the scope of Jewish suffering were so disproportionate that this simplistic system broke down.

Jewish religious thinkers had to rethink and reimagine their covenantal relationship with Yahweh. The idea that their pain somehow will bring redemption because Israel is God’s “suffering servant” ended up becoming an extremely prevalent thought process of the time. The Book of Job portrays this thinking perfectly as it analyzes the question of undeserved suffering and attempts to rationalize the pain that they, as God’s servants, must endure.

Being able to cope with the destruction of their society as they knew it required theological flexibility and imagination. Out of the ashes, new schools of thought emerged in Judaism focused on collectively grappling with evil and unjust suffering within God’s providence. Groups like the Essenes turned to this idea of apocalyptic thinking, picturing their present troubles as part of the cosmic battle between good and evil coming, before eventually a new age in which a Messiah would come to earth and liberate the faithful. This apocalyptic thinking would become extremely popular throughout the rest of Judaism as a whole, and could even be seen throughout the teachings of Jesus in the Gospel.

Torah Becomes a Portable Identity

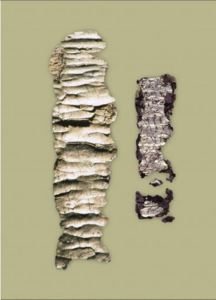

(The Ketef Hinnom Silver Scroll Amulets, the oldest surviving portion of text from the Torah: https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-artifacts/inscriptions/miniature-writing-ancient-amulets-ketef-hinnom/)

(The Ketef Hinnom Silver Scroll Amulets, the oldest surviving portion of text from the Torah: https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-artifacts/inscriptions/miniature-writing-ancient-amulets-ketef-hinnom/)

In the face of such unprecedented dispersion and exile for the Jewish leadership, they found that keeping their identity and faith alive took center stage for their religion. This need to preserve their heritage and origins from generation to generation sparked scribes to write down the oral history, stories, and laws that had been passed down for centuries. According to Brettler, the trauma of exile and the loss of the temple spurred the editing of books within the Pentateuch, most noticeably with the creation story being moved to the beginning of the Pentateuch, providing structure to the rest of the narrative. Scribes would edit works to more prominently emphasize traditions that would serve to aid in the preservation of Jewish identity, such as circumcision. The acts of bringing together these scriptures and history provided the dispersed Jewish people with a set of cultural roots that were not tied to one place.

The observation of the Torah’s laws on dietary restrictions, Sabbath, circumcision, rituals, and ethics took on new importance in maintaining Jewish identity. When they no longer had access to the temple in Jerusalem and its cult, obeying biblical law became one of the only ways Jewish ethnic and religious identity could remain. This pushed Jews to make keeping kosher, honoring the Sabbath, and getting circumcised extremely significant indications that could distinguish Jews from Gentiles across the diaspora. The biblical commands that once were solely centered on temple rituals suddenly shifted to be practiced within homes and communities.

Studying those scriptures became increasingly important with the temple now gone. The pre-exilic priests responsible for sacrifice were almost completely replaced by local scribes, rabbis, and scholars as interpreters of scripture and law. The local rabbi became the authority on how to correctly live a lifestyle that the Torah would approve; at the same time, scribes made it a priority to read scripture for the public, and the synagogue ended up becoming the place for the study of sacred texts.

By Jesus’s time, centuries after the Exile, this “text culture” approach had developed into the enthusiastic Rabbinic debate about tradition over ethics and about the meaning of Torah that came together to form early commentaries like that of the Talmud. The Judaism of Jesus’s day put the study and discussion of texts at the very center, unlike the sacrificial rituals of pre-Exilic times. This emergence of biblical analysis and scholarship within the Jewish community was only possible because of the Exile diaspora, which shifted Judaism’s focus from the temple to the text.

Impact on Post-exilic Judaism

The consequences of the Babylonian Exile’s cultural trauma and transformations became apparent in the following centuries, from Persian rule to early Roman rule leading up to Jesus’s birth. The returning Jewish exiles were changed people, adhering more closely to ideas present in the Torah and excluding Samaritans from their culture. According to Pieter Venter, a former theological studies professor at the University of Pretoria in South Africa, they not only strongly resisted intermarriage with foreign women, but they actively discouraged it and believed it could pollute the holy status of the nation. The extreme reinforcement of this identity boundary hints at the ethnic partisanship that developed in the post-exilic period.

By Jesus’s time, 500 years after their return from exile, the Second Temple period of Judaism was thriving with diversity and energy. Bart Ehrman, a biblical scholar at UNC-Chapel Hill, explains how the Judaism that Christianity emerged from was rooted in the scriptures, rituals, institutions, and beliefs that were the legacy of the Exile. The scriptural canon, rabbis, synagogues, practices like Sabbath and Passover, and theological concepts all reflected many beliefs of those in the Babylonian Exile.

The Exile’s decentralization of power created unrest within separatist groups of Judaism, as different groups argued over what practices were correct and the proper interpretation of scripture. Jewish sects like the Essenes, Sadducees, and Pharisees inherited the traditions formed in exile, and often believed they were the only true way to be Jewish. Our knowledge the Judaism in Jesus’ time is only because of the historical exile that forced Jews to record their traditions and beliefs.

So, in looking back, the many competing groups that specifically marked the Jewish religion under Roman occupation emerged from the seeds planted after the temple’s destruction centuries before. The investigation of the scriptures and the expansion of new ideas were invigorated, and the horrors of the Exile helped create a transformation of Judaism that would turn it into the textually driven religion of Jesus’s day.

Legacy of Judaism in Jesus’s Time

By stepping back and looking at the full historical context, we can really appreciate how the Babylonian Exile served as the domino that radically changed Judaism and put it on the long course that led to the religion as Jesus experienced it. When we talk today about biblical Judaism, we talk about the post-Exilic religion. Core foundations of the religion, like sacred scriptures, rabbis, synagogues, the law of the Torah, apocalypticism, and messianic expectations, were all molded by how steadfast leaders responded to the conquest and exile that caused so much suffering throughout the nation.

The Babylonian conquest, destruction of the First Temple, and mass exile of Jews ripped up the roots of Judaism and could have ended the ancient Jewish religion and culture altogether. But in the centuries between rebuilding Jerusalem under Persian rule and Jesus’s birth, Judaism rebounded through the adaptation of traditions and oral histories, allowing for the religion’s survival. The necessity of survival compelled innovation.

Out of the ashes of the temple, decentralized local gatherings emerged as the location of religion. Home-based practices like Sabbath rituals and festivals replaced the need for temple rites. Study and commentary on sacred scripture became the focal point of religious life with the deconstruction of any priestly sacrificial cults. An overwhelming amount of new theological ideas appeared amid the destruction of old certainties. Normal citizens took on more ownership of their faith tradition with the lack of religious leaders available to complete their prior cult practices.

The diversity of beliefs and practices that characterized Second Temple Judaism emerged from the spiritual void and diffusion of power left by the destruction of the First Temple centuries before. Ehrman emphasizes that this exile-hardened Judaism, coping with crises through its texts and ideology, served as the immediate backdrop for the beginnings of early Christianity with its messianic adaptations.

A Closing Thought

The Babylonian Exile was a devastating catastrophe that destroyed the First Temple, ripped the heart out of the Jewish nation, and sent shockwaves throughout Judea. But it was also a period of innovation and creativity as leaders created new ideas that were needed for Judaism to continue. By necessity, the vacuum left by Exile led to the reinvention of a new Judaism that was more flexible, portable, and community-oriented. Out of the pain rose renewal, and the new Judaism that came from this provided the immediate background for early Christianity’s origin. Jesus practiced the Judaism present after the exile, so without this horrific time, Christianity would have never formed the way it has. So, while potentially disastrous, the horrors of the Babylonian Exile helped shape both the transformation of Judaism and the founding of Christianity that we are familiar with today.