The Undemocratic Process of Partisan Gerrymandering

Chapter 11 of the Struggle for Democracy touched on various key elements of the United States Congress such as constitutional foundations, representation, congressional elections and voting, legislative processes and checks and balances. This chapter is particularly significant in our overall examination of the effectiveness of American democracy because it brings formal politics to the center stage. In this post, I want to address one of the most monumental threats to modern American democracy: gerrymandering.

Of the three branches of government, the House of Representatives should be the most representative of the people’s will. It should live closest to the people. However, today, the House of Representatives is the least representative branch of our government. This lack of representation in the House stems from state legislators ability to cheat the electoral redistricting system by gerrymandering. As described in the text, gerrymandering is when legislators draw the electoral districts of a state to help their party win seats. In turn, the party in power gains more congressional and legislative seats than it should according to the state’s electorate. This occurs in two ways, “packing and cracking”. “Packing” is when legislators draw the districts so that the opposing party’s voting power is concentrated in one district, which weakens their overall power in the state. “Cracking” is when legislators draw the districts so that their opposing parties voting power is spread throughout the state, making them the minority in most districts. Not only does gerrymandering undermine the opposing parties representation, it also furthers the United State’s deep partisan divide by decreasing the amount of competitive seats in congressional elections. Thus, incumbents in “safe seats” have little incentive to build compromise with their opposition.

It’s unquestionable that the process of congressional district redrawing will always entail some political calculation, however, there is a point where too much political calculation severely undermines the opposing parties representation, as I will demonstrate below.

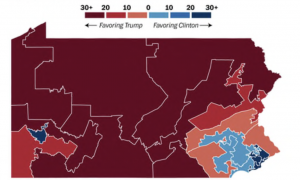

Considering the only rules for redrawing districts is that they must be equal in population and contiguous, it’s clear the legal framework of redistricting does little to prevent state legislators from abusing their power. Take Pennsylvania’s case for instance. After the 2010 census, Republican legislators in Pennsylvania drew some of the worst district lines to date, which, unfortunately for Democrats, were used in the past three congressional elections.

(District 7 is the worst…)

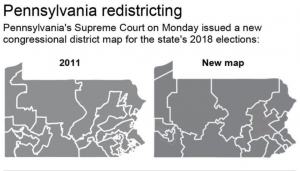

Although Republicans only received about half the statewide vote, they maintained control of thirteen of the fifteen seats in the House each year as a result of this blatant gerrymander, while Democrats, who won between 46-51 percent of the statewide vote, held the same five seats year in and year out. Recently, however, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ordered Republican state legislators to redraw the state’s districts in time for the 2018 midterms. The court held that the districts state Republicans drew in 2010 violated the state constitution because they were “aimed at achieving unfair partisan gain” and “undermines voters’ ability to exercise their right to vote in free and equal elections.”

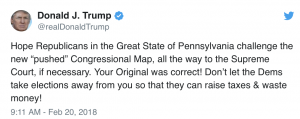

Indeed, the new map reflects the partisan composition of the state more so than the initial map that was heavily tilted toward Republicans. However, Republicans have been reluctant to accept the new map as it is and intend on challenging it in court. In February, Donald Trump urged Republican leaders to fight the new map via Twitter:

Regardless of what happens in Pennsylvania, I’m happy to see action being taken against gerrymandering. However, it is unlikely Pennsylvania’s decision will further the momentum against partisan gerrymandering across state borders other than setting an example. Going forward, I would love to see a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that would put an end to this shameful and undemocratic practice. Or, perhaps, a 28th amendment against gerrymandering. The former is probably more realistic. In fact, the U.S. Supreme Court is currently deliberating a case challenging the Republican drawn districts in Wisconsin and the Democratic drawn districts in Maryland, so stay tuned. Given that the federal court is hearing cases from both Democrats and Republicans, this would be an optimal time for the court to appear unbiased partisan wise in implementing new regulations on partisan gerrymandering.

What are your thoughts on partisan gerrymandering? Also, if you could implement a 28th amendment, what would it be?