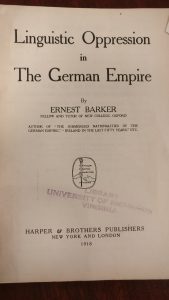

L inguistic Oppression in the German Empire by Ernest Barker further illustrates a vivid picture of the German man’s imposition of his values, his kultur, and his supposedly superior identity onto those he ruled; he does so by using language as a vessel for such assimilation. Barker refers to three specific instances of linguistic assimilation and oppression in the areas ruled by the German Empire: Prussian Poland, Danish Slesvig, and Alsace-Lorraine. (This is not to say that the empire was succesful in all their attempts.) He presents how the German Empire imposed onto these regions the “use of an alien speech–a speech which is the vehicle of a culture that is not their own” (Barker 6); subsequently, the native languages of these regions are oppressed by law, affecting everything from education and religion, to legal matters and home life itself.

inguistic Oppression in the German Empire by Ernest Barker further illustrates a vivid picture of the German man’s imposition of his values, his kultur, and his supposedly superior identity onto those he ruled; he does so by using language as a vessel for such assimilation. Barker refers to three specific instances of linguistic assimilation and oppression in the areas ruled by the German Empire: Prussian Poland, Danish Slesvig, and Alsace-Lorraine. (This is not to say that the empire was succesful in all their attempts.) He presents how the German Empire imposed onto these regions the “use of an alien speech–a speech which is the vehicle of a culture that is not their own” (Barker 6); subsequently, the native languages of these regions are oppressed by law, affecting everything from education and religion, to legal matters and home life itself.

As established by the empire’s efforts in Poland, the general model it followed then on is described as follows: The empire mandates the use of the German language, and in some cases German alone, in schools. Furthermore, it adds in that religious instruction should also be taught in German, subtly enforcing anti-Catholic sentiment by forcing children to learn their religion in a language not their own (Barker 14). The oppression eventually bleeds into the household, such as through an 1899 decree in Poland that required families to converse purely in German. Even the young and deaf-mute are required to be taught in German, thus making communication with their loved ones difficult (Barker 14).

Furthermore, enforcing the use of German in local meetings, gatherings. and press/news effectively barred freedom of expression or speech. Thus, German oppression attempted to bring about “intellectual stagnation” (Barker 18) onto those they ruled. (One would assume that German imposition of values they deemed superior would “elevate” the Polish. I believe the stagnation only goes to show how misguided the oppressive efforts were.)

All of it leaves us to wonder why the German Empire would impose such restrictions in the first place. The easy and simple answer would be to say that the Germans were deluded in their radical nationalism. While correct overall, I believe some depth would benefit our understanding of the pre-war German mindset.

According to Barker, the German “folk” felt their culture’s spirit “within” them and sought to show others the majesty of the German collective; “the ‘culture’ of the folk–the nation or people–thus becomes a sacred tradition; and the language in which it is enshrined becomes, as it were, the vehicle which carries the holy ark of the covenant” (Barker 4). (It seems contradictory to me how German radicalism prioritized ‘breaking out’ as the individual, yet the ideology itself created a uniform German collective.)

Barker also explains how, because they kept their language so detached from everyone else’s by refusing to adopt phrases, the German language stood as “self-sufficient” (Barker 5), which I believe may be why while they believed it would stand out, it instead became hard to learn for other learners.

Most importantly however, Barker says that the oppression was enforced because Germans believed that they were doing their regions a favor; they believed that since their language and culture were so universally good, they must be doing good by forcing it on their subjects. After all, “if men are forced to use it, they are after all being “forced to be free” (Barker 8) from the shackles of traditional inferiority.

Admittedly, we are left to trust Barker and his claims, which one should always do with a sizable amount of salt. If true however, the German people, in their own deluded way, believed that they were doing good “sacred” work and bettering those around them. This justification drove them, it drove them to try to oppress and silence everything they couldn’t fluently speak themselves.

phlet I picked to examine is “Rural Education in War,” written by Warren H. Wilson and published in 1917 by the Division of Intelligence and Publicity of Columbia University. This pamphlet was published as part of the Columbia War Papers, a series of similar pamphlets meant to convince Americans to help solve wartime problems and fulfill their national duty.

phlet I picked to examine is “Rural Education in War,” written by Warren H. Wilson and published in 1917 by the Division of Intelligence and Publicity of Columbia University. This pamphlet was published as part of the Columbia War Papers, a series of similar pamphlets meant to convince Americans to help solve wartime problems and fulfill their national duty.