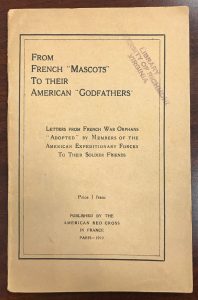

After having perused through several pamphlets from the Galvin Rare Book Room, I selected one entitled “From French ‘Mascots’ to their American ‘Godfathers'”. Published by the American Red Cross in 1919, this document reveals the translated letters that were exchanged between French children and American soldiers, as part of an initiative to monetarily support struggling French families. These letters are clear evidence of the lasting bond between the American Expeditionary Forces and over three thousand little ones who were impacted by the events of World War I.

The first letter that I encountered was written in 1918 by a small French girl whose father had been missing since the onset of the war. Marie-Louise Patriarche, the first “orphan” to be adopted through the program, expressed her ultimate gratitude in being an American soldier’s “little mascot” (8). Ultimately, this letter represents the encouragement that members of the United State’s Army needed in order to perform their duty. The letter provided support for a soldier to persevere in the dreadful conditions presented by trench warfare, as Marie-Louise “loves [them] with all her heart” (8). Additionally, the letter was tangible evidence that a soldier’s effort was worth the fight. Marie-Louise depended upon her “godfather” to survive through the war. This dependence must have strengthened an American’s will to fight.

Another letter, written by Jeanne Claudel, displayed the impact of the “godfather” upon his “orphan”. As Jeanne listed his academic accomplishments, “1st Prize in French History, 1st Prize in Arithmetic, 2nd Prize in Writing,” it was clear that the French children wanted their “godfathers” to be proud of them (15). Surely an American soldier felt honored to have such an influence over a little one. Moreover, after losing his father, Jeanne considers the American soldier “to [him] somewhat like [his] father” (15). It appears that the “orphan” needed more than money; his relationship with the soldier comforted him. Although this initiative was primarily to raise soldier’s spirit and to support poor French families, the emotional connections that developed between child and soldier were just as important.

The last, and perhaps most touching, letter that I read was written by a boy named Marcel Lefevre. Containing a description of the father’s gruesome death and gratitude towards the “godfather”, the letter highlights the importance of this program: to convince soldiers to fight to protect the innocence of the youth. Not only did the Great War prematurely expose children to death, but it was a time that lacked youthful joy. Marcel’s description of how he “[shudders] at the sound of guns” was heartbreaking (25). It instilled in me a desire to restore his innocence and prevent him from experiencing any more hardship. I presume that soldiers experienced similar emotions.

Overall, the letters from this pamphlet demonstrate the need for emotional connections during times of war. As seen in Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, the war emotionally strained soldiers; therefore, cheerful letters, such as the ones provided in this pamphlet, instilled hope. Letters, regardless of how unimportant they seem, carry a profound influence.

Whoa. Serious tear-jerker! I’m curious about the audience. I can see soldiers being interested, but I suspect these were sold more broadly. So it’s worth considering what audiences at home took from such a pamphlet.