by Lillie Mucha

My vaguely-considered curiosity presented in response to the previous chapter – “it is important to recognize that the physiology and hormones in males and females are different” (Mucha 2015(a)) – was greatly expanded on after reading the essay “Taking Science Seriously: Straight Thinking About Spatial Sex Differences” by Nora S. Newcombe. I had been assuming that sex differences are essentially bad, and idea based on multiple occurrences of hearing arguments about the (not really) all-important difference in math testing scores for females and males. It seemed logically at the time that the difference must be a bad thing to cause so much controversy. The explanation I thought was that either women were not as smart as males or the men were unfairly dominating the world of science. I believe now that sex differences are natural, though magnified by inaccurate stereotypes that can breed a crucial lack of understanding about the meaning of male and female.

The Arguments for Natural Sex Differences

A meadow vole chewing on grasses

In “Taking Science Seriously,” Newcombe presents the argument that, while possibly caused by sex hormones, sex differences are not supported evidence to have developed through evolution because of any reproductive advantage. She claims that the “Man the Hunter” (men must track and hunt animals for survival) and “Man Who Gets Around” (like meadow voles, men must travel to reproduce) theories are inadequate to explain why greater spatial ability would have helped prehistoric males survive and impregnate the females. In addition, she says that since higher spatial ability has benefits for both sexes but no apparently significant advantage for males in comparison, there is no reason why both sexes would not develop the skill. Since hormone levels are related to spatial ability, but the ability cannot simply be explained as “male hormones promote it and female hormones restrict it”, Newcombe suggests that the sex difference in cognitive ability is simply a secondary trait of the necessary sex-specific hormones.

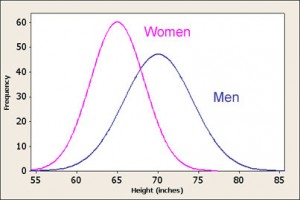

Newcombe does not take the “extreme ‘nurture’ position: that males and females are biologically indistinguishable, and all relevant sex differences are products of socialization and bias,” as defined by the evolutionary psychologist Steven Pinker (Pinker & Spelke 2005). While Newcombe does disagree with Pinker’s speculations regarding the evolutionary aspect of sex differences, the two agree that sex differences do naturally occur. Many studies show the apparent difference in sexes for cognitive abilities, especially related to hormone levels (Halpern 1997; Hausmann et al. 2000; Lenroot & Giedd 2010). I agree with the statement made by Doreen Kimura, that to believe sex differences do not exist “is basically incompatible with scientific principles, because it encourages the ignoring of a large body of opposing research” (Kimura 2007). By focusing only on the convergence of male and female scores as infants or elementary school children, the important sex-related period of puberty is incorrectly construed as being an unnatural influence.

“Natural” is Transformed into Something Else

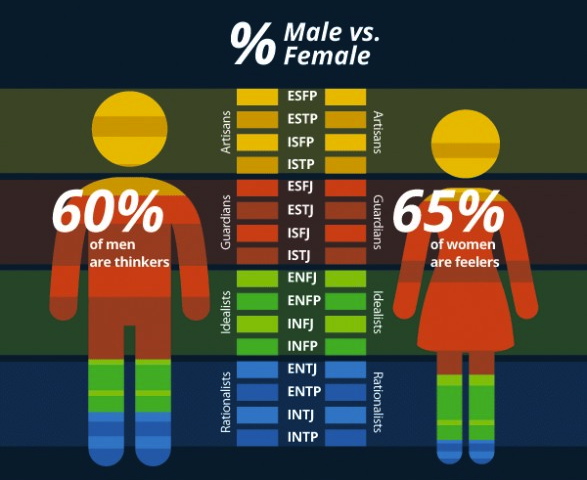

The biology of the sexes is a relevant and realistic understanding of how sex differences come about. Unfortunately, stereotypes about the differences between men and women also exist, and complicate the matter significantly. As it has been introduced in the book before, teaching and learning mindsets play a large role in how stereotypes manifest in the abilities of men and women (Mucha 2015(b)). The biological differences between males and females are not inherently bad, but when they are unnaturally magnified by gender stereotypes, the opportunity for discrimination snowballs.

Sources

Kimura, D. (2007). “Underrepresentation” or Misrepresentation? In Ceci, S. J. & Williams, W. M. (Eds.), Why Aren’t More Women in Science? (pp. 39-46). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Newcombe, N. S. (2007). Taking Science Seriously: Straight Thinking About Spatial Sex Differences. In Ceci, S. J. & Williams, W. M. (Eds.), Why Aren’t More Women in Science? (pp. 69-78). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Print.