alternatively titled: “How Many Discussions does it take to Challenge an Assumption?”

by Lillie Mucha

Elizabeth S. Spelke and Ariel D. Grace respond to the debate over Lawrence Summers’ comments with a deep understanding of the assumptions his statements have implied. In their essay, “Sex, Math, and Science,” they explain the empirical behind the belief that males and females have no sex differences that would explain the difference in employment in science. Citing studies of primarily infant cognitive abilities, they say that the sexes are equal in ability. I agree with Spelke and Grace’s position that discrimination is more to blame for the lack of women in science than biology is. In our age of emotionally and politically founded arguments, an explanation with good analytical depth is hard to come by through popular media. What we think of as getting deep into a discussion can often be not deep enough. So let’s discuss.

Various Gender Labels

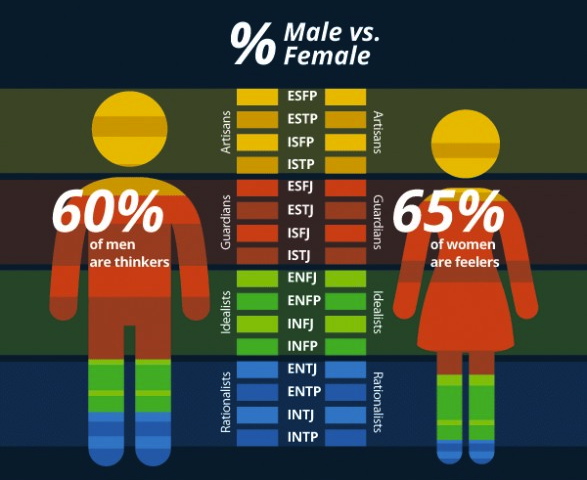

I was immediately drawn to the gender argument of “systemizers” and “empathizers” (58). The theory generally states that males are innately “systemizers,” or people who are better at learning mechanical patterns, and females are innately “empathizers,” or people who are better at learning emotional patterns. This theory reminded of the gender difference present in Myers Briggs Type Indicator. In one study, only 30% of female teenagers identified as Thinking types, while only 40% of male teenagers identified as Feeling types (Bayne 1997). This falls in line with gender stereotypes we are overexposed to.

Directly in contradiction to this assumption, Spelke and Grace supported the idea that males and females are cognitively the same in infancy, a time in which social constructs have had very little time to make a difference on the child’s expressions (58). It’s an important step to take in studying infants. By the time participants are adolescents, their brains have developed in many new ways. They have been exposed to gender norms for over a decade, and puberty has started to affect their development in sex-specific ways. Spelke and Grace go on to say that older children do tend to approach problems differently: males more often use geometry and spatial reasoning skills while females use landmarks and algebra skills to do the same tasks (59).

Multiple Kinds of Bias

At this point, the gender bias starts to make a significant difference. Since math problems can be solved two ways, and either could be more effective than the other on any given problem, the possibility that the answers to tests are written with a male cognitive advantage is very likely. According to Spelke and Grace, the male-favoring difference on the Math SAT test is a poor predictor of female ability in college compared to males’. However, the work cited for this information did not conduct an experiment to determine this result, and I can imagine a compounding variable that could be in play: college enrollment.

The assumption is that women who are equally qualified but scored lower than men on the Math SAT are earning equal grades and bachelor’s degrees in college as men. While SAT test-takers are certainly intending on applying to college, there are some – usually on the low end of scores – who end up not applying or not being accepted. What would influence a test-taker not to apply to college? Female people significantly underrate their level of competence in a situation dominated by successful males (Correll 2004). A female low-scoring test-taker would more likely believe that they aren’t cut out for college, reflecting on both their decision and dedication to apply to colleges and universities. Also, people give evaluations with inherent gender bias against females, even if unintentional, as was shown by many studies in Spelke and Grace’s essay.

Summary

As for myself, I became aware of the fact that Spelke and Grace’s constant use of the phrase “no sex difference” led me to start thinking that males and females are truly identical. However, it is important to recognize that the physiology and hormones in males and females are different. How much this has to do with differences and similarities in the brain I do not know, but I am looking forward to exploring this topic in more detail in the next chapter, “Taking Science Seriously: Straight Thinking About Spatial Sex Difference.”

Sources

Image source: link