by Lillie Mucha

“‘Underrepresentation’ or Misrepresentation,” an essay by Doreen Kimura, introduced a new opinion to me. With supporting evidence, she claims that the math and science fields have not been discriminating against women, but rather women have a lower aptitude and lower interest in the sciences. She claims this is a natural, biologically-based deviation, and efforts to “artificially raise the numbers of women in science” are irrational.

“‘Underrepresentation’ or Misrepresentation,” an essay by Doreen Kimura, introduced a new opinion to me. With supporting evidence, she claims that the math and science fields have not been discriminating against women, but rather women have a lower aptitude and lower interest in the sciences. She claims this is a natural, biologically-based deviation, and efforts to “artificially raise the numbers of women in science” are irrational.

Biological predispositions

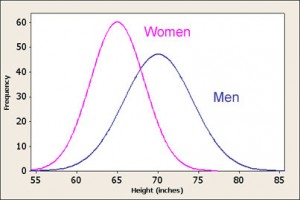

I agree with Kimura’s statement that the sexes are gifted with different levels of ability with regards to specific cognitive tasks. Evidence supports that a biological difference between the composition of the sexes does account for a consistent, reasonable difference between the average female and average male.

There is a slight inconsistency in Kimura’s words that I would point out: an entire paragraph is devoted to explaining that the, “[c]ognitive differences between men and women vary greatly in magnitude,” but in the conclusion Kimura states that there is “substantial overlap between men and women on all cognitive functions.”

Why the sudden change? To my understanding, the essay focuses largely on “men and women at the high end” of scores, reasoning that the top scorers will naturally go on to work in math and science and earn doctorates. What I think this approach does is totally ignore the males and females who are not at the top of high school math tests, but do go on to lead successful careers in math and science.

Does the data actually fit the pattern?

“The pattern fits well,” is what Kimura says about the varied distribution of women earning degrees in specific science fields as compared to their “math talent” and interest levels, but provides no evidence to support this theory. While biology may very well be a factor of the trend of women in science, I’m interested to know if there have been any experiments to test this pattern. Since there is “substantial overlap between men and women on all cognitive functions,” one would expect that there would be substantial overlap in the employment and interest of math and science fields.

What I think this reasoning brings to light is the idea that top scorers on math tests are not the only people who go into math and science. Similarly, the closer-to-average scorers don’t exclude math and science from their options. There seems to be an assumption that anyone who has ability should work in that field, but this approach doesn’t take into account the passion and dedication to learning of people who start with lower test scores. A lot of the people who go into math and science fall within the “substantial overlap” area. Considering this, is it really so reasonable that women make up 24.8% of computer and mathematical occupations in the U.S. (U.S. Department of Labor, 2009), yet 50.8% of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010), or is some other factor contributing to the trend?

The Other Factor

Of course, the name of the other factor most under question is discrimination. It shouldn’t be worrying to us that males and females aren’t represented equally just because we want the numbers to show a perfect 50/50 divide. There should be room for variation based on biological differences which do exist, and the slight back-and-forth shifting in numbers between the years. The importance is not in the numbers, but in the implications behind the numbers.

Are females underrepresented in math and science purely because of biological differences? If so, how can a “significant overlap” explain the 3:1 male-to-female ratio in computer and mathematical fields? Are gender discrimination and social constructs of the old days – stretching back not “over the past 2 decades,” but over multiple centuries – keeping women from pursuing and excelling in fields they would otherwise enjoy?

Sources

U.S. Census Bureau, 2010 Census of Population, Profiles of General Demographic Characteristics.

Image source: link