“Wait, you play World of Warcraft? And you’re a girl? But you look so… normal.”

I have had this conversation, and many variations of it, countless times over the past several years. Inherent in this question are a number of preheld notions and biases. One is that that only boys play role-playing games like World of Warcraft. Another is that any girls that do play are either very masculine or very… weird. And by extension, there is the unsaid implication that the realm of gaming is a place for men. Is this because men are inherently better at action video games, or is their expertise simply a result of practice and experience? I propose that in relation to gaming, and also the issue of inherent cognitive abilities between males and females, it is impossible to completely disentangle the biology from the background.

Video Games and Spatial Cognition

When we think of action, strategic, or role-playing video games, and the video game culture in general, many of us think of an almost entirely male-dominated world. This is because the vast majority of the population that plays these types of games is male. While women play their fair share of social and music/dance video games, more violent and action-packed games are notoriously void of women gamers. Men also play, on average, about 11 more hours of video games weekly than women and start playing at an average age of 6.6 (as opposed to 9.3 for women) (Phan, 2012).

Interestingly, action video games such as these have been shown to increase spatial cognition ability in both genders. A study at the University of Toronto found that playing action video games can cause changes in “sensory, perceptual, and attentional abilities that are important for many tasks in spatial cognition”. The article also states that action gaming can improve more complex spatial skills, such as mental rotation (Spence, 2010). Spatial cognition and mental rotation are skills that have been shown repeatedly to be significantly greater in males than females. (Newcombe, 2007). This gender gap in the ability to visualize 3D objects in space is an important skill in many science, mathematics, and engineering fields. Therefore, it has often been proposed as one of the main reasons that there are so few women in STEM fields.

One of the key pieces in this argument, however, is that men are inherently better at spatial cognition and that spatial ability is genetic. There are certainly genetic factors (which I will be exploring in the next section). Yet, as we saw earlier, there are activities like video gaming that can cause significant increases in spatial cognition in both genders. When it comes to measuring innate spatial abilities between genders, how do we separate the biological from the environmental? Do more males choose to play video games because they inherently have better spatial abilities, or do activities like video games increase the average male spatial ability down the line?

The Biological vs. The Environmental

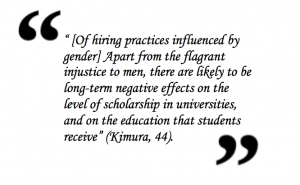

In her essay “Taking Science Seriously: Straight Thinking about Spatial Sex Differences”, Nora S. Newcombe discusses the sex differences between men and women in regards to spatial ability. She claims that the most plausible current hypothesis from a biological standpoint is that men and women differ in their sex hormones, the levels of which correlate to spatial ability. Doreen Kimura provides support for this idea from her own research, saying, “prenatal androgen levels are almost certainly a major factor in the level of adult spatial ability” (Kimura, 2007). This would indicate that men are predetermined to have better spatial abilities as adults simply as a result of their hormones. This information could then be used to explain the gender gap between men and women in STEM fields. After all, if the answer is purely biological and women just don’t have the right hormone levels for high functioning spatial skills, it would seem that women aren’t “cut out” to be in STEM.

The issue with this line of thinking, which Newcombe explores in her essay, is that spatial ability is highly malleable. Newcombe explains that spatial abilities in both genders have increased so rapidly in the past century that it would have been impossible for a correlated gene to have changed in that time span (also known as the Flynn effect). She also explores some results from her own meta-analysis. When training undergraduate students in tasks aimed to increase spatial ability (one of these being computer games), Newcombe found that both genders increased their spatial abilities dramatically with effects that lasted for months and showed no signs of leveling off. While there was no convergence in the genders in spatial ability, even after training, she also found that the increases in spatial ability were “far larger than the typical sex difference” (Newcombe, 2007). While Newcombe mentions the latter briefly, she neglects to expand on its implications. If spatial ability can be changed so greatly through academic exercises, musical instrument training, or video games that it can easily span the gap between the genders, how can we say with any certainty that the spatial ability gender gap is biological or innate in origin? What if the difference in spatial ability between the genders is mostly a reflection of how each gender is treated in society and the types of activities each partakes in? We saw earlier how males generally start playing video games earlier in life than females and do so for far longer spans of time. If video games have been shown to increase spatial abilities enough to exceed the gender gap, then who’s to say that they are not responsible for the differences that we see? Even though certain differences in genders may seem biological, there is no way to truly test this theory. Because spatial skills are so malleable, we would in no way be able to account for the multitude of environmental differences and backgrounds that could have extreme effects on these skills.

Of course, it is rather drastic to assume that action video games are the reason for the gender gap in STEM fields. There are certainly numerous other reasons that women don’t pursue math and science careers, most of which have nothing to do with spatial ability. The above logic also operates under the assumption that women don’t participate in other spatial ability-improving activities at equal levels as men, such as playing musical instruments or solving puzzles. But until we can determine the effects that all of these behaviors have on spatial abilities – and at what rates males and females partake in them – we cannot confirm that differences in spatial ability are genetic or inherent. When it comes to our current studies of spatial ability and the gender gap, we simply cannot disentangle the behavioral from the biological.

References

Kimura, D. (2007). “’Underrepresentation’ or Misrepresentation?” Why Aren’t More Women in Science? Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Newcombe, N. S. (2007). “Taking science seriously: straight thinking about spatial sex differences”. Why Aren’t More Women in Science? Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Phan, M. H., Jardina, J. R., Hoyle, W. S. (2012). “Examining the Role of Gender in Video Game Usage, Preference, and Behavior”. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomic Society, 56(1), 1496-1500. doi:10.1177/1071181312561297

Spence, I., Feng, J. (2010). “Video games and spatial cognition”. American Psychological Association, 14(2), 92-104. doi: 10.1037/a0019491